Sadly, I’m no aristocrat and this isn’t the 18th century, but I did go to Italy in search of art and architecture. Part 2: Rome.

I've been covering art and architecture recently, so an immersive visit to Italy seemed like a good idea. I wanted to see for myself the palaces, the churches, the frescoes, the paintings (or whatever remained of them) that had such a great influence on Western art. This concept is nothing new, of course. The idea of a Grand Tour goes back to the 17th century when it was standard practice among the more enlightened members of the high nobility to spend a few years traveling through Italy to study – or pretend to – the classical world through its ruins.

Unfortunately I don’t sit on a dynastic fortune, so my Grand Tour was compressed into an intensive three-months period which took me from Venice to Rome, with a dozen cities and more than a hundred museums in between. What follows isn’t a collection of amusing travel stories – sorry! – but my attempt at making sense of the artworks I've seen. I included below specific recommendations for museums and architecture with a map in case you're inspired, and also a short food and wine summary of the regions I visited. Part 2: Rome.

The Food of Rome

While the Roman shepherds in 800 BC only had their sheep – providing them meat and pecorino cheese – the neighboring Etruscans already raised wheat and wine and bred beef and hogs. During the imperial era, exotic roast birds graced the dining tables of the wealthy but when the Empire collapsed, so did the network routes that supplied them. (Waverley Root’s seminal book, The Cooking of Italy, is assisting me.)

Roman cuisine is vegetable-heavy. The beloved artichokes appear as carciofi alla giudia (Jewish style), deep fried in olive oil, and carciofi alla romana, braised and tucked with herbs and garlic. Pecorino and ricotta are the two Roman cheeses, both of sheep's milk, while mozzarella is more common in the south, near Campania, its origin.

Of the Roman pasta sauces, carbonara, cacio e pepe, Amatriciana (from the town Amatrice), and gricia are most common, many made with pecorino cheese and guanciale (pork jawl). The Roman pizza, rectangular and crunchy, is less pliant than the Neapolitan and traditionally topped simply with oil and onions.

Popular meat dishes today include porchetta (a symbol of Rome), abbacchio (a baby lamb), and saltimbocca (thin slices of veal seasoned with sage and prosciutto). Some Roman trattorias still serve lunch based on a fixed weekly schedule, for example gnocchi alla Romana on Thursday, baccala on Friday, and tripe on Saturday.

Rome is the capital of Lazio, a region with plenty of wine but far from the best in Italy. The wine production is centered on the Castelli Romani (Roman Castles), a half circle cradling Rome from the south. If you try a Roman wine, make it the white Frascati. Not exactly memorable but Roman and traditional.

Ancient Roman Sculpture at the Capitoline Museums and the Borghese Gallery

A walk up to the Capitoline Square atop the Campidoglio is a spatial experience no one in Rome should miss (Michelangelo is to thank). Those buildings up there house the wonderful sculpture collection of the Capitoline Museums. Starting with Sixtus IV in 1471, some of the popes "gave back" to the city its Roman-era artworks, which landed in this building, hence its claim to be the first public museum of Europe. The visit convinced me that the Romans could do anything from stone and bronze, that they weren’t bound by technical limitations.

The bronze Boy with a Thorn (1st century BC) is playfully brilliant, while the elaborate marble reliefs in the grand staircase of the victorious Marcus Aurelius show what happened when the empire's greatest sculptors received a generous budget. Most famous of all is the 2nd century AD equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, of which a copy stands on the square outside. It only survived because people had wrongly thought it depicted the pro-Christian Emperor Constantine (pagan monuments were demolished and melted down).

Of course, propaganda was dear to the hearts of the emperors, perhaps for none more so than Constantine, who in the 4th century AD commissioned an enormous statue of himself to be placed in the Basilica of Maxentius. Today, its absurdly sized remains are in the museum's courtyard – the marble feet alone are longer than two meters (Stalin would've been proud).

The Borghese Gallery is an excellent place for contextualizing antique artworks, because they're set against those of later periods. The early-Baroque Borghese villa and its expansive park, now public, was the summer estate of Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577-1633), the extravagant art-collecting nephew of Pope Paul V.

It was at the Borghese that neoclassicism finally clicked with me. It was impossible not to see the parallels between Antonio Canova's Venus Victrix (1805-1808) and the nearby Roman figures: All of them gentle, calm, timeless. Not clamoring for attention but with a discernible presence and flawless anatomy.

Sublime Roman Walls

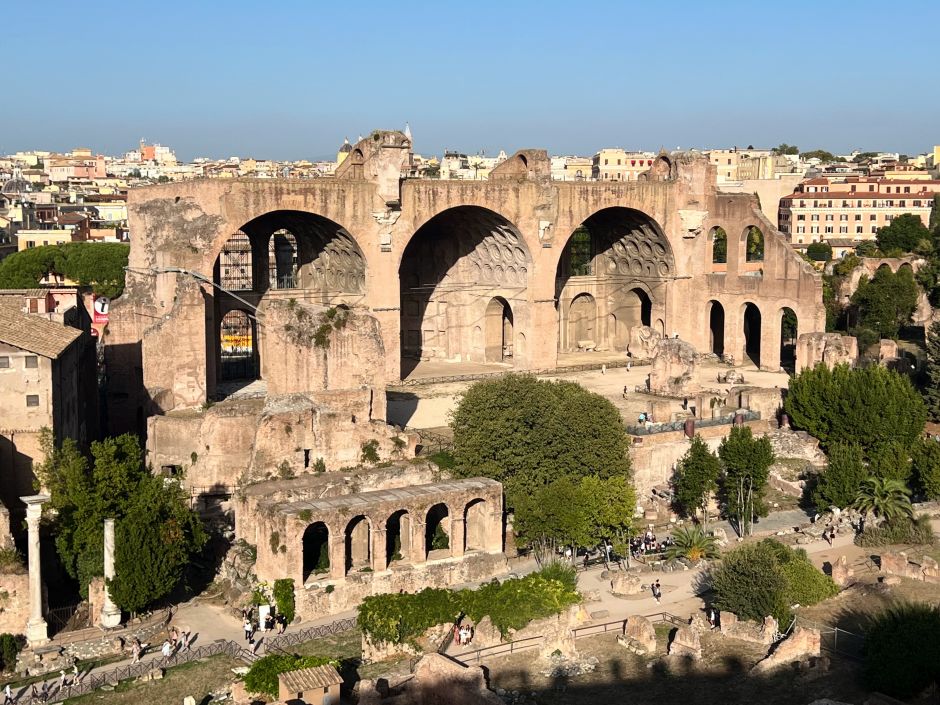

A highlight of my trip was admiring the Roman Forum at sunset. Those lonely marble columns silhouetted against the sky. The thick Roman walls of Trajan’s Market with the deep shadows they cast. The beautiful proportions of the Pantheon with its impossible dome. The enormity of Caracalla’s Baths. Did they really build these things two thousand years ago? The thought messes with the head.

Until much of the Republican period (around the 1st century BC), Rome imitated the buildings of the neighboring Etruscians and Greeks and most of its architects were Greek. But with improved engineering skills – Roman vaulting techniques and the use of concrete-and-brick construction – they were able to meet the demand for new building types. Whether in Rome, in the Middle East, or in North Africa, the ever-expanding Empire needed churches, basilicas, triumphal arches, amphitheaters, theaters, stadiums, bridges, markets, baths, aqueducts, mausoleums, and residential houses.

By the 1st century AD, the Romans were able to put up enormous (Colosseum) and inventive structures (Pantheon, Trajan's Column) and started to play around with new decorative elements. They created the Composite order, for example, which combined an oversized Ionic and a Corinthian capital and was considered the most noble. Renaissance architects 1,500 years later did something similar: they used the Roman forms as a starting point and made their own deviations from them.

Still fresh in my mind, I saw connections everywhere. Those circular holes on the spandrel of Palladio’s Basilica in Vicenza? Surely a reference to the medallions on the Arch of Constantine. The Villa Rotonda? A combination of the Pantheon and a classical church front. Alberti’s coffered barrel vaults at the Sant'Andrea in Mantua? They rhyme with the Basilica of Maxentius. Brunelleschi? He must have seen the Basilica of Saint Sabina on the Aventine Hill.

Ancient Rome and the Renaissance come together into a single building of the Santa Maria degli Angeli church. A few years before his 1564 death, Michelangelo transformed the cold room (frigidarium) of the Baths of Diocletian into the nave of the new church so that the enormous scale of the baths can still be appreciated today. The eight red granite columns stand in their original position and the characteristic lunette windows of Roman baths light the interior.

Boring High-Renaissance Architecture?

In the beginning of the 1500s, the ambitious Pope Julius II (1443-1513) set his mind on reviving the power and glory of ancient Rome under his leadership. This entailed an immense building program for which he summoned the leading painters – including Michelangelo and Raphael – and architects, turning Rome into the art capital of Italy. The most important architect was Donato Bramante (1444-1514) and his circle of assistants.

Initially Bramante & Co. mirrored the early-Renaissance style of Filippo Brunelleschi, for example his Pazzi Chapel (1443) in Florence: They applied strict proportions, gentle pilasters, unobtrusive window pediments, and subtle rustications. Examples include the Palazzo della Cancelleria, the Palazzo Farnese, and the Palazzo Farnesina, all of them with timid – flat and planar – surface decorations. A friend said that these buildings looked a bit boring and I sort of agreed with her.

Bramante’s Tempietto (1502), hidden in a cloister on the Janiculum hill, is considered a milestone because he broke up the monotony of the flat surfaces. He used sharp-cut windows, deep niches, a round shape. There are solids and voids – the building feels lively and three-dimensional. Perhaps it was inspired by an ancient Roman temple (maybe the one in Tivoli), but it isn’t an imitation. The drum with the hemispherical dome are Bramante’s invention.

After Bramante’s 1514 death, his colleagues explored his rhythmical play of wall exteriors – Baldassare Peruzzi’s Palazzo Massimo (1532-1536) in Rome has a curved facade – but it was left to Michelangelo to lead the way, culminating in what came to be known as Baroque architecture.

Michelangelo in Rome

Michelangelo was a Tuscan through and through, but most of his works are actually in Rome. Enough has been written about the Sistine Chapel (1508-1512), so all I’ll say is that my visit was less than ideal. The whole Vatican Museums felt like an airport when flights are delayed, chaotic and crowded, with the guards constantly nudging people to move. The Sistine Chapel is predictably magnetic, of course. It's surreal to see the originals of what inspired so much of European art (Libyan Sibyl!, Creation of Adam!). The lower-level also contains treasures, for example Perugino’s Delivery of the Keys. I hope to return one day when things are less crowded, which will never happen.

It isn’t much easier to get private time with Michelangelo’s Moses, part of that long delayed and much reduced funerary monument for Pope Julius II, relegated to the San Pietro in Vincoli church. The figure of Moses is completely amazing. There’s power, there’s pain, there’s wisdom, there’s charisma. “The Burden of a Leader,” would be an apt subtitle. Sigmund Freud famously psychoanalyzed the sculpture, which is usually thought of as showing the moment when Moses grew angry at the sight of his people worshipping idols, prompting him to break the tablets of stone (Freud thought that Moses's rage has just passed).

Michelangelo worked on three Pietàs throughout his long life, the most famous of which is located in the Saint Peter's Basilica (finished in 1499). It's the work of a 23-year-old genius eager to assert himself. The depiction of Christ's lifeless body lying collapsed in Mary’s lap bespeaks the sensibilities of a completely mature artist. The technical brilliance is shocking. All this from a slab of marble. Michelangelo's later Pietàs, in Florence and Milan, are less detailed but equally expressive.

By the last thirty years of his life (1534-1564), Michelangelo was a celebrated artist across Italy and the popes inundated him with architecture projects. In the 1540s, he created a charming square atop the Capitoline Hill. As you approach the trapezoid from below, the space is flanked by two synched-up buildings, tilted and leading your gaze to the bronze equestrian statue of Emperor Marcus Aurelius standing at the center, slightly elevated. Countless architects have imitated Michelangelo's Renaissance details, especially the colossal pilasters on all three square-facing facades.

Michelangelo also designed a playful gate by the old city walls in eastern Rome, the Pia Porta (1561-1565). The late-period Michelangelo is on full display. The broken and embedded pediments, the giant dangling guttae, and other idiosyncratic details provided a rich toolkit for the coming generations of Baroque architects and sculptors.

And there’s of course the Saint Peter’s Basilica. Michelangelo, with a few brilliant strokes of a pencil, transformed Antonio da Sangallo’s overly complicated design to the radial central plan initially envisioned by Donato Bramante. He established the main axis with a portico, but everything about Michelangelo’s exterior – including the colossal pilaster system wrapping the building – would have led the eye to the glorious dome at the center. His answer to Brunelleschi's famous dome in Florence a hundred years earlier.

Unfortunately, after Michelangelo’s death, two additions rendered his dome almost invisible when standing too close to the church. These were Giacomo della Porta's unnecessarily long nave, and Carlo Maderno's unnecessarily big facade. Still, Michelangelo’s dome dominates Rome's skyline and it became a much-imitated symbol for centuries to come, both in Rome and around the world, both in church and civic buildings.

The Bologna School of Classicism

One of the most important movements in the history of painting was the Bologna School, which monopolized much of Europe for two hundred years, from about 1600 to 1800. Its origins go back to Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) and his cousin Ludovico and brother Agostino, who in the 1580s established an art school in Bologna that ushered painting back to its classical roots.

The Carraccis cut the cords of the confusing – but often fun – Mannerist-style that had been popular across Italy, from Tintoretto's lopsided canvases to Bronzino's polished artifice. They equally derided Caravaggio’s imitation of imperfect reality. Nature, they believed, is to be embellished and idealized. The most important members of the Carracci cradle were Guido Reni, Domenichino, Giovanni Lanfranco, Il Guercino, and Francesco Albani, artists who moved from Bologna to Rome for periods of time in the early 1600s.

The leading figure, Annibale Carracci, struck a wonderful balance between Raphael's classicism and Michelangelo's energy. His most famous work is the ceiling fresco at the Palazzo Farnese (1597-1608), showing the loves of mythological gods, anchored by a fun-looking party hosted by Bacchus and Ariadne (entry by advance appointment only as the high-security building today is the French Embassy).

The Bologna Classicism conjures up in me an image of an elegant mythological or Biblical scene in which slender figures frolick in the green landscape, perhaps framed by Roman architecture. Similarly, the Bologna Classicism was at the root of the 17th-century grand manner, known for its oversized and classically arranged figures (walk into any Baroque church in Rome for an example). Much of the Italian Baroque and even Rococo paintings can be traced back to this source.

Notwithstanding the masterpieces and personal touches – I'm a big fan of Guido Reni's wistful silvery tones, for example – it's not without reason that many art historians in the 19th century relegated this type of stuff to the back-burner for being generic and overly formulaic.

Caravaggio in Rome

Caravaggio lived in Rome for most of his short but eventful life and the majority of his paintings are located in Rome’s museums and churches. I had struggled with the few that hang in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, but now that I’ve seen his full range, I’m a firm believer of his brilliance. The Borghese Gallery is a good place to start because it turns out that Cardinal Scipione collected paintings too, in fact, he assembled more Caravaggios than most people (six pieces).

Caravaggio’s sharply painted early works from the 1590s – the Boy with a Basket of Fruit, the Sick Bacchus, the Fortune Teller – have their own charm (neoclassicism two hundred years before neoclassicism?), but his legacy is rooted in the religious themes from 1600 onward. When he combined the extreme use of light and shadow with extremely realistic and slightly mystical depictions of Biblical figures. Has anyone before painted Saint John the Baptist the regular teenage boy he might have been? Madonna’s mother, Saint Anne, old and wrinkled? Madonna with cleavage? Saint Jerome with dirty nails? (All of these at the Borghese.)

To me, these paintings are more powerful and persuasive than irreverent or scandalous. Of course the clergy, especially lower-level priests, didn’t always think so. The French church in Rome (San Luigi dei Francesi) famously rejected Caravaggio’s peasant-looking and illiterate Saint Matthew and requested from him a more respectable version that still hangs at the center of the Contarelli Chapel. Fortunately, they gave the green light to the Calling of Saint Matthew, an astonishing and spirit-lifting coming together of Caravaggio's realism and magical use of light.

And who else, besides Michelangelo, gained such a following without trying to? Caravaggio schools sprouted across Europe after his 1610 death. In Rome led by Orazio Gentileschi, in Naples by Jusepe de Ribera and Artemisia Gentileschi, in Utrecht by Hendrick ter Brugghen and Gerrit van Honthorst. Some of these artists’ best paintings are also at the Borghese, but the most detailed survey of caravaggism is found at Rome's National Gallery in the Barberini Palace, with four halls dedicated to the various strains of chiaroscuro, from Giovanni Baglione to Orazio Borgianni, from Carlo Saraceni to Bartolomeo Manfredi.

The Old Masters Collections in Rome

The Borghese Gallery has one of the best collections in Rome for old masters paintings (be sure to book ahead because tickets often sell out weeks in advance). In addition to the Caravaggios and the Bologna painters mentioned above, there's an emotional late-period Titian – Venus blindfolding Cupid – and one of his brainiest canvases called Sacred and Profane Love. In Correggio’s Danae the wrinkled bedsheets evoke a bedroom scene after lovemaking. Bonus: the Deposition of Christ by Raphael (1507), proof that even a genius as he couldn’t persuasively paint figures in motion, at least not yet. Lanfranco's astonishing quadratura fresco in the Sala della Loggia (1625) upstairs will surely mess with your sense of reality.

The Doria Pamphilj Gallery also holds crowd-drawing old masters. There are three Caravaggios, landscapes by Paul Bril and Jan Brueghel, and dozens of paintings by the Bologna School, especially Francesco Albani. Above all stands, in a room to itself, Diego Velazquez’s portrait of the Pamphilj pope, Innocent X (1574-1655), with that famous cold gaze that pierces a hole in the gut.

The National Gallery in the Barberini Palace is worth seeing for the striking Baroque Villa housing the collection, designed by the greatest names of the 17th century: Maderno, Bernini, Borromini. The collection has a broad sweep, from Byzantine paintings up to 1800, usually matched by depth. A highlight is Raphael's phenomenal portrait of Margarita Luti (1518), his likely mistress, better known as La Fornarina, the baker’s daughter from Trastevere.

With Raphael, it's always hard to peek beneath the surface glory, to unearth the stuff his subjects are made of. But here, those black eyes of hers reveal the depth of the relationship they might have had. Before leaving, it's worth trying to take in Pietro da Cortona's exuberant fresco in the grand salon, conveying the Barberini family's earthly and celestial powers.

Visitors often ignore the Vatican Museum’s picture gallery and head straight to the Laocoön, the Raphael rooms, and the Sistine Chapel despite a terrific collection (and less crowded halls). It's here that you can chart Raphael’s evolution that culminated in his flawless last painting, the Transfiguration (1520). Other highlights: Giotto's Stefaneschi triptych, Caravaggio's Deposition, Guido Reni's Crucifixion of St. Peter (with caravaggian influence), and Domenichino's Last Communion of St. Jerome.

In addition, there are three stunning palace-galleries in Rome with mainly B-level paintings. Palazzo Colonna, Galleria Spada, and Palazzo Corsini. Here, the elaborate Baroque interiors – the Colonna family still lives in their block-sized palazzo – are as much part of the experience as the artworks.

Bernini in Rome

The Borghese Gallery is best known for its nine works by the young Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), the greatest sculptor – also architect and painter – of the Baroque period. Bernini’s figures immediately appear more polished, tense, and dynamic than the nearby antique sculptures (only the Laocoön at the Vatican Museum could compare in intensity). As if Bernini captured them in a pivotal moment: David winding up his sling; Aeneas rescuing his family from the burning Troy; Pluto seizing the helpless Proserpina.

Bernini's virtuosity astounds most in the mythical story of Apollo and Daphne, where he shows when Daphne, in her quest to avoid the advances of Apollo, turns into a laurel tree. Her slender limbs and her soft hair are enveloped by ligneous toughness and we see in real time as her gentle body loses itself to the encroaching laurel tree that comes to be a symbol of Apollo – all this narrative carved from a piece of marble by the twentyfive-year-old genius. Including the individual blades of laurel leaf and their stalks.

A late-period bust of Gabriele Fonseca (1668-1674), the doctor of Pope Innocent X, proved to me that Bernini wasn't all fireworks. That he could express layers of human emotion with nuance and sensibility, in this case the doc's religious devotion. This largely unknown masterpiece is located in the Basilica of Saint Lawrence in Lucina, just off Rome's main street, the Corso.

Bernini didn't just invent what we now call Baroque sculpture, but he was the first to combine architecture, sculpture, and painting in a way that the individual elements melt together. As if he transformed a painting into three dimensions. Using golden rays and hidden sources of natural light, he often recreated the impression of a miracle or a religious vision, most famously with the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647-1652) in the Santa Maria della Vittoria church.

The outrageous depiction of Saint Teresa enraptured shows her bathed in light and stabbed in the heart by a cherub with a flaming arrow, the sign of her union with God. The list of exquisite details is endless. Members of the Cornaro family, who commissioned the work, kneel in high relief on the sides, impressed by the miracle taking place before them (a theater within a theater). The heavenly sky overhead combines painted and three-dimensional floating putti but the difference is impossible to tell. The marble details are so singular and beautifully composed that they might have made even Adolf Loos blush.

Bernini's famous twisted baldachin (1624-1633) at the Saint Peter's Basilica doesn't just bring the attention back to Michelangelo's seminal dome overhead, but, viewed from the church nave, its bronze columns dramatically frame the papal throne and the radiating image of the holy dove (1656-1666). As chief architect of the Saint Peter's, Bernini and his workshop churned out papal tombs, sculptures, and the Doric colonnades outside, whose main purpose was to position the crowd to a vantage point from which the church's outsized facade no longer blocked the view of the dome.

My favorite Bernini is the Saint Andrew Church on the Quirinal. It's one of his few architecture works, although this small, oval-shaped, spirit-lifting tempietto is as much an outsized sculpture as it is a building. The semicircular portico signals to visitors the vertigo-inducing spatial experience waiting inside. Almost everthing – the color scheme, the projections, the lighting – directs our eyes to the apotheosis of Saint Andrew, the fisherman-turned-apostle, sitting atop the broken pediment of the altar niche and waited upon in the heavenly golden dome by fishermen-putti. Bernini's coffered dome lined with ribs was emulated by later generations (he got the idea from Pietro da Cortona).

Some thoughts that kept recurring in my head during the Bernini days: At which point does this aggressive ornamentation and three-dimensionality become too much? Can people even register the incredible details? Does the whole exceed the sum of the parts? Part of the reason that Loos’s marble accents are still celebrated today is because nothing rivals them; he let them take center stage.

I'll mention two Berninis that didn't do much for me. The Rivers of Paradise (1648-1651) fountain on Piazza Navona felt too bombastic, and the impossible tomb of Pope Alexander VII (1671-1678) in the Saint Peter's Basilica would be an example of kitsch in my book if I didn't know it was by Bernini. ("How much folded jasper can we fit into the alloted space?")

It’s against the above background, all the theatrics, that I experienced what has to be the greatest irony of the Baroque period: the tomb of the master. Bernini’s own final resting place. The simplest, most inconspicuous thing, hidden in the back of the Santa Maria Maggiore church. It made me wonder: who had the last laugh here?

Borromini in Rome

I used to think of Francesco Borromini (1599-1667) as the curmudgeon right-hand man of Bernini. Envious and resentful of the great master whom he could never surpass. I no longer think that. Perhaps the two of them shouldn't even be compared, as they often are, since Bernini was primarily a sculptor, Borromini an architect. If Bernini's sculptures embodied the greatest of the high-Baroque, so did Borromini's building.

The novelty of Borromini's architecture was movement: A spatial dynamism, an interplay of the concave and the convex, walls undulating in a rhythm, projecting and receding. He always carefully held the separate parts together with a sequence of outsized columns and cornices, as in the San Carlino alle Quattro Fontane (1640-1680) and the Sant'Ivo alla Sapienza (1642-1667) churches, two of his best works. Notably, both of them are largely free of interior decorations. Unadorned white spaces defined and brought alive through architecture alone.

Borromini didn't just stretch the classical forms to their limits – squeezed window pediments projecting outward, illusionistic coffered half-domes, compact sculptural facades with almost no wall space left to them. He also introduced new motifs with endless creativity. Take the strange tower of the Sant'Ivo alla Sapienza, with its stacked inverted scrolls, pyramid, and spiral, or the way he played with the classical Corinthian cornice, replacing its egg-and-dart motifs with whatever struck his roving mind. I kept thinking: in another hand, this would surely turn into awful kitsch. Not with Borromini.

This might sound like light-hearted mannerism, but Borromini's churches can lift the spirit, even for a non-religious person. Standing under the honeycomb-patterned white dome of the Quattro Fontane conveys the power of divinity more persuasively than most other churches I've been to. The same is true for the soaring verticality of the Sant'Ivo, its dome rushing and racing to reach the heavens.

Since 1927, the Hungarian Academy in Rome has been located inside the Falconieri Palace. This grand building lines Via Giulia, named after the Renaissance pope Julius II, who started to overlay Rome's winding medieval streets with long avenues leading to the Vatican. In the 1640s, a wealthy Florentine merchant family, the Falconieri, tasked Borromini to extend their Renaissance palace.

Borromini dressed up the otherwise unremarkable facade with herms ending in falcon-heads (the family's symbol). He added a stunning top-floor loggia, visible from the garden. We can only imagine what the views are like from up there, but the garden is open to the public. Inside, he decorated twelve of the rooms with rich ceiling stuccoes, featuring a dense collection of his signature floral motifs and putti that form the architectural design.

A similar ornamental program – much bigger in size – appears in the Basilica San Giovanni in Laterano (1646-1649), where Borromini spiced up the nave, including the clerestory, and the aisles. Not all details are decipherable, but totally striking in their effect.

Pietro da Cortona in Rome

Pietro da Cortona (1596-1669) was the greatest high-Baroque painter in Italy but he isn't so well-known, perhaps because he was an exact contemporary of the superstar duo, Bernini and Borromini. Cortona dialed up the Bologna School's quiet classicism, creating vast, fiery, exuberant frescoes. His greatest work is the enormous ceiling painting in the Barberini Palace (1633-1639) celebrating the achievements of the Barberini pope, Urban VIII. Cortona's other dense masterpiece: the frescoes at the Santa Maria in Vallicella church, known as the Chiesa Nuova (1647-1660). Here, uniquely, his frescoes ring the 1608 altar painting of Peter Paul Rubens, the more famous giant of the high-Baroque.

Cortona was also an architect, designing the widely admired Santa Maria della Pace church (1657), known for its semi-circular portico and lively facade (and Raphael's frescoes of sibyls and prophets inside it, evidently inspired by Michelangelo). He also did the Santi Luca e Martina church (1635-1650), where he is buried, with a perplexing and much imitated coffered dome. This church falls under people's radars because of its peculiar location right by the Roman Forum, its convex front almost touching the 3rd century AD triumphal arch of Septimius Severus.

Cortona set the stage for the monumental fresco paintings in Rome in the second half of the 17th century. Perhaps the most spectacular of these high-Baroque works are Giovanni Battista Gaulli's mystical Adoration of the Name of Jesus (1674-1679) in the Gesù, and Padre Andrea Pozzo's allegory of the missionary work of the Jesuits (1691-1694) at the Sant'Ignazio. Both of these churches belong to the Jesuits and are located near each other in the city center.

From the Pope to Mussolini: Palazzo Venezia

The least visited and most spectacular museum in Rome is inside the fortress-looking Palazzo Venezia, across the outsized 19th-century monument to Victor Emmanuel II. Once the residence of Pope Paul II (1417-1471) and the Venetian ambassadors to Rome, the grand salons housed the office and the private quarters of Benito Mussolini in the interwar period (his lonely desk looked absolutely comical in that giant room).

You'll most likely have the Loggia di Benedizioni to yourself, an exterior gallery from which the pope used to give his blessing to the masses with wonderful views onto the Capitoline Hill. The museum also has a bunch of terracotta and plaster sculptures of famous Baroque works, majolica dishware from Federico Montefeltro's Renaissance court in Urbino, and a few gorgeous paintings by the likes of Giuseppe Maria Crespi and Giorgione.

The Decline of Rome

Notwithtstanding such 18th-century treasures as the the Spanish Steps (1723-1725), the Trevi fountain (1732-1762), and the magnificent sculptures of Antonio Canova (1757-1822), the decline of Rome started already in 1667 with the death of Pope Alexander VII, the last great patron of the arts. Papal investments dried up and Paris, under the centralized rule of Louis XIV, became the new center for art and learning. Rome was gradually relegated to an open-air museum of ancient ruins, no longer the capital of modernism. 18th-century travelers came to Rome – from Winckelmann to Goethe to countless English lords – to study the past, not the present.

More than three hundred years later, in the current day, this is still largely the case. The difference is that in the 18th century, a trip to Rome – the Grand Tour – was the privilege of the elite class, whereas these days most people can afford a visit. The democratization of travel and mass tourism, of course, came with downsides, which are especially evident in Rome. The only way to evade the crowds: become a night owl. Visit the Pantheon, for example, late at night, when it has cleared of fellow tourists.

I don't want to end on a sad and nostalgic note, so I'll recommend two modern museums. The first one is the fairly well-known Maxxi, in northern Rome, inside a characteristically eye-catching Zaha Hadid building. The place is dedicated to 21st century art, so some of the exhibited items won't stand the test of time, but it's a refreshing venue nonetheless after the classical ruins and Baroque churches of downtown. Here, you can also glimpse artsy and chic Romans whom you won't find in the city center even if their life depended on it.

The other one is the National Gallery of Modern Art in the Borghese gardens. International heavyweights abound – Monet, Van Gogh, Mondrian, Kokoschka, Giacometti, Cy Twombly – but the collection is mainly about Italy's bests from the 19th and 20th centuries.

Note the unique spatial experience. The first of the vast halls is playfully crowded with paintings the old-school way, then things get airy and sparse. An avantgarde sculpture here, a Canova Hercules there. Explanatory wall texts nowhere. The exhibition, evidently, was made for promenading through it (tons of natural light and the palatial vibes help). This isn't the place for overanalyzing every artpiece. Let your eyes guide you. And enjoy. A museum in Rome that isn't crowded with people!