A product of the Enlightenment, Pyrker (1772-1847) was a Jeffersonian figure in his varied interests and drive for public good. His legacy is still felt in Hungary but he’s largely forgotten today.

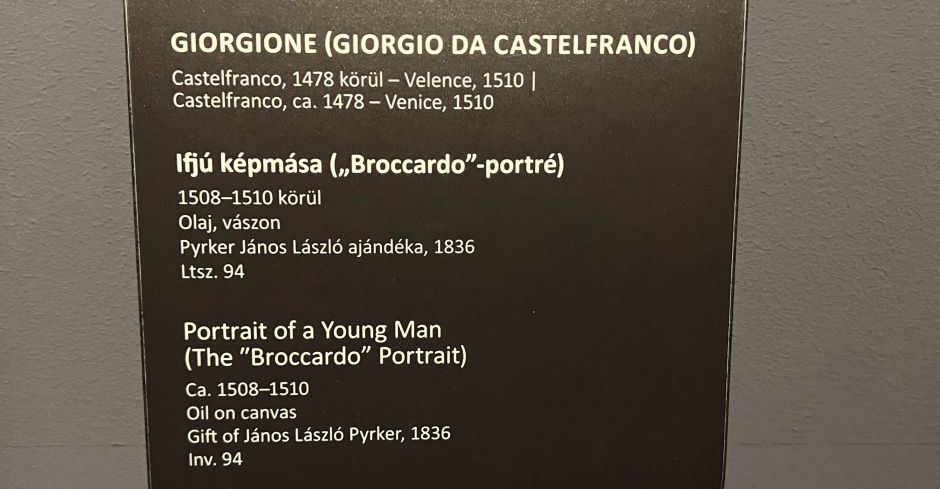

I noticed his name at Budapest’s Szépművészeti, the greatest fine arts museum in Hungary: “Gift of János László Pyrker, 1836,“ read the dusty-blue wall texts, one after the other. What kind of person could afford these masterpieces in early 19th-century Hungary? What kind of person would give them away for free? How did I not know of this? I spent the past few weeks perusing Pyrker-monographs and Pyrker archives in Eger – a 50,000-resident city in eastern Hungary where he was Archbishop between 1827 and 1847 – and found his life so fascinating that it’s worth describing in detail.

Unlike the Hungarian upper crust of his time, Pyrker wasn’t born into wealth. His father, a small-time estate manager, managed to send the precocious Pyrker to schools in Székesfehérvár and Pécs but university was out of the question. Pyrker instead landed a job in Buda, in 1790, where he showed more interest in reading Schiller and Goethe than the clerk duties he was supposed to perform at the Palatine’s Office.

Despite his passion for literature, the twenty-year-old Pyrker decided to become a priest – a choice he later described as prudent – and, by the recommendation of a friend, moved to the Cistercian Abbey of Lilienfeld in Lower Austria. He spent the next thirty years there, earning the monastery’s respect and being elected abbot in 1812. All this time, he kept nourishing his mind: he read literature in the evenings, wrote epics and dramas, learned French and Italian, and attended the intellectual salons of nearby Vienna.

Crucially, it was in Lilienfeld that Pyrker became friendly with the Habsburg family. Emperor Francis I (1768-1835) regularly lodged at the scenic abbey – which had a designated royal quarter – and appreciated Pyrker’s company, especially his wide learning and deferential manners. Just how fond of him the Emperor was became clear in 1818, when he requested that Pyrker leave the order to become the Bishop of Szepes in northern Hungary. Two years later, he made Pyrker the Archbishop of Venice (so-called Patriarch).

Pyrker had been uneasy about these promotions; he preferred the quiet life of Lilienfeld but Francis needed trusted church leaders, especially in Venice. The recalcitrant Venetian Republic had recently lost its long-held independence to the Habsburg Monarchy, so Francis ensured that all top-level positions were filled with his most loyal lieutenants – in fact, Pyrker was the first non-Italian Archbishop of Venice (he did speak Italian).

To appease Pyrker, Francis granted him the Villa Giovanelli Colonna, a stunning 17th-century Palladian palace outside Venice along with a salary increase. Having this “direct line” to the Emperor was totally unprecedented for other members of the Hungarian elite and explains why Pyrker was able to get things done so efficiently in Venice and later in Hungary.

Venice was an ideal place for Pyrker to pursue his greatest passion: painted artwork. He attended the annual shows at the Gallerie dell'Accademia, and when touring the churches of his diocese, he’d study each altar painting in detail. He never missed a chance to visit a private villa with an art collection. As his own collection started to take shape, his new friends in Venice – people he hosted for lunch at the Villa Giovanelli: professors, scientists, artists, art dealers – helped him find treasures. If this sounds like atypical behavior for a priest, it was in fact; however, by all accounts Pyrker performed his clerical duties with utmost conscience and care. (He must have been very good at time management.)

While also buying contemporary works, Pyrker’s purchases focused on the greatest Venetian period in painting, the 16th and 17th centuries. Gentile Bellini, Giorgione, Paolo Veronese, Palma il Giovane, Bernardo Strozzi, Tiepolo, Guardi, Belloto. Decades later, when his collection was moved to public museums in Hungary, it turned out that many had been misattributed. It’s tempting to think that his Italian “friends” fleeced him, but attribution was far from scientific back then and things could go both ways. For example, what Pyrker labeled as a “circle” painting turned out to be by Giorgione himself.

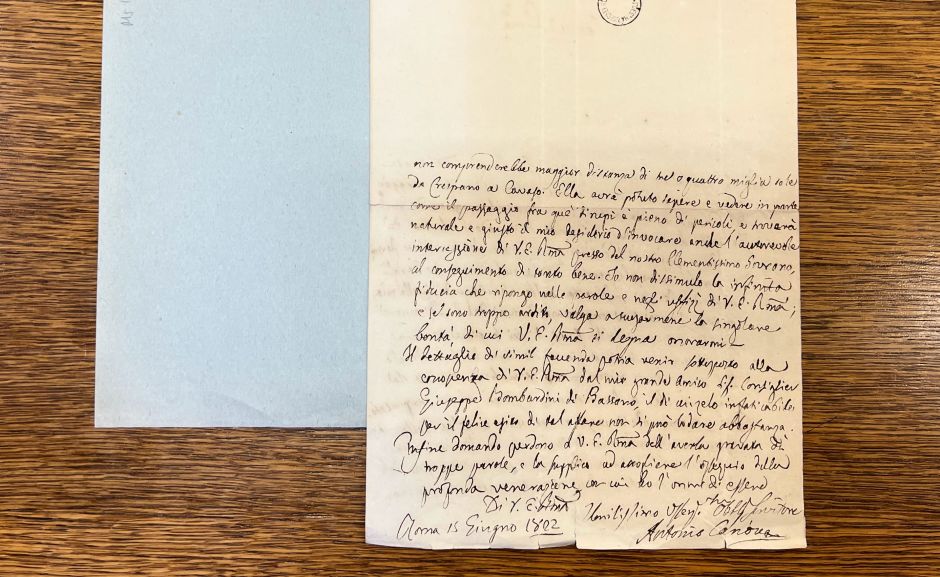

Some of Pyrker’s possessions came by the time-honored way. Not only as Archbishop but in virtue of having the ear of the Emperor, people asked him all sorts of favors, and they rarely arrived empty-handed. Once, the greatest sculptor of the 18th century, Antonio Canova, pleaded with Pyrker to finance a road construction leading to his home village of Possagno, giving weight to his appeal with a Paolo Veronese painting and a statue of Saint John the Baptist by his own hand. (The request was granted, despite the fact that the Veronese later turned out to be a workshop piece; Canova’s letter is still held at the Archbishop’s Library in Eger.)

Just as he finally settled in at Venice, in 1827 the Emperor dispatched Pyrker to fill the vacancy at the Archbishopric of Eger, one of the biggest dioceses in Hungary (then days of carriage ride from Budapest; today, less than two hours by train). Returning to his homeland after nearly four decades was bittersweet and a bit of a culture shock. “The quiet Eger after the noisy Venice,” he wrote with understatement. He immediately set out to transform the provincial Eger from the backwater he felt it was, capitalizing on his wealth and international connections.

Touring the diocese, he noticed that teachers themselves often struggled with basic reading and math, so he founded and paid for the first Hungarian-language teacher’s college in the country. The two-year course covered math, literature, Biblical studies, and music (many teachers in small towns doubled as cantors). Still in 1827, he set up a drawing school to improve the skills of local carpenters, builders, and other craftsmen. He also intended to launch Eger’s first girls school, but that took place only after his death, financed in part from money Pyrker left for it.

He established an improvement commission to regulate building construction in Eger, banning the unnecessary parceling up of land, penalizing the owners of vacant lots, and setting standards for facade details. He transformed the Eger Castle into a historic monument. This was the site of the famous 1552 battle where the vastly outnumbered Hungarian troops had defeated the Ottoman army and which previous bishops used as a stone quarry for their building projects. Pyrker landscaped the area, brought back the marble tomb of the battle’s hero-general, István Dobó, and built a chapel around it.

Following in the footsteps of the Ottomans, he took advantage of Eger’s rich reservoir of thermal water by expanding the baths’ capacity and promoting Eger’s medical tourism (still a draw for visitors today). He ensured that Jewish people were permitted to settle in Eger and ply their trade uninterrupted, enforcing the national law of 1840.

Pyrker also built a new cathedral for Eger. He thought the old church of the Archdiocese looked like a village parish, so he tasked the Rome-trained star architect in Hungary, József Hild, with the design. By 1837, within just six years, the enormous building was up, its imposing Roman portico towering over Eger’s Baroque center.

It’s still the third biggest church in Hungary today and a striking example of neoclassical architecture, complete with a pedimented columnar porch, a hemispherical dome, and lunette windows that bring to mind the ancient baths of Rome. Pyrker hired Venetian sculptors and painters for the decorative program. Marco Casagrande’s stone statues of Hungary’s canonized kings, Stephen and Ladislau, with the church’s portico rising behind them, is still a haunting sight.

As in Venice, Pyrker liked to host intellectuals at the Archbishop’s Palace in Eger. During these gatherings, his private string quartet recruited from Italy performed music and guests were free to view his by-then immense painting collection. He extended the southern wing of the palace to make space for the hundreds of pictures he brought back from Venice. Judging by visitors’ notes from the 1830s, the picture gallery was a grand spectacle, completely peerless in Hungary. Pyrker allowed artists to study them and make copies and even regular visitors were usually permitted to tour the halls.

In 1836, the same day when the construction of a National Museum was approved by the Hungarian Diet in Pozsony, Pyrker announced that he would donate 192 paintings to the museum. With this, Pyrker established the first public picture gallery in Hungary and set an example for the high aristocracy for most of whom this sort of charitable behavior was completely alien. Pyrker’s paintings, still today, comprise some of the most treasured possessions of the Szépművészeti Múzeum.

Even as high priest, Pyrker continued to write literature. Today he’s generally viewed as a B-level author of epics that nonetheless stirred quite a debate in 1830s Hungary. Pyrker, whose native language was Hungarian, wrote his books in German and his two best known works – Tunisias and Rudolf von Habsburg – both narrate the heroic deeds of German emperors. Predictably, this didn’t sit well in Reform Era Hungary where patriotic sentiments were flying high (the famous poet Mihály Vörösmarty, wrote a poem eviscerating Pyrker’s German sympathies).

Pyrker likely preferred German because he expected a greater audience in the more advanced and more urbanized German territories. Whatever the reason, it’s a mistake to judge him through a nationalist prism: Pyrker was a product of the enlightenment, he probably didn’t harbor any kind of patriotic sentiments; not German, nor Hungarian.

This also explains why Hungary today isn’t peppered with Pyrker monuments and Pykrer streets. Posterity usually prefers a fiery patriot to a quiet doer, no matter how meaningful. I’ve found that even in Eger few people remember him. (Among the employees of the Archbishop’s Library, there’s a small Pyrker fan club, which I’ve now proudly joined). You, however, dear reader, could honor the memory of János Pyrker by visiting the Szépművészeti Múzeum in Budapest. Or the charming city of Eger, where his legacy still imbues the whole town.

I’d like to express my gratitude to Erzsébet Csorba and Zoltánné Szász at the Archbishop’s Library in Eger for their kind assistance.