The Museum of Fine Arts (Szépművészeti) has an unexpectedly grand old masters collection.

“The fine arts museum was the greatest discovery of our Budapest trip,” said my friend a few months ago. Like other tourists, he didn’t expect to stumble into an astonishing old masters collection in this neck of the woods. As most good things in Budapest, this hallowed institution harks back to the golden years of Austria-Hungary (1867-1918), when a confluence of capital and political will rapidly transformed the city into a thriving metropolis with cultural offerings to match.

How did this vast collection come about? After all, by the end of the 19th century the Habsburg treasures had been deposited to Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum and Hungary's "own" line of royalty ended with the Renaissance King, Matthias, whose paintings and illustrated codices had been long dispersed.

The pivotal year was 1871, when the Hungarian state acquired the artworks of the financially strapped Miklós Esterházy. The purchase included 637 singular old masters paintings – for example those by Raphael, Correggio, Bronzino, Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Guercino, Claude Lorrain, Jusepe de Ribera, Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, Frans Hals, Francisco Goya – together with thousands of drawings and etchings that the princely family had accumulated. So valuable was the Esterházy collection that other museums, including the Louvre, submitted competing bids for it, but by then it had been a national cause in Hungary to “bring home” the paintings, which until 1865 hung in the family’s Vienna palace.

Other pictures came from enlightened Hungarian aristocrats and high priests who bestowed their private collections on the museum. For example, in 1836, János László Pyrker, the Archbishop of Eger, in eastern Hungary, donated 192 paintings; for years, the art-loving Pyrker had been the Patriarch of Venice during which time he assembled an amazing body of Venetian old masters including Giorgione’s famous Portrait of a Young Man. Or János Pálffy (1829-1908), one of the wealthiest people in Austria-Hungary, who gave away 178 precious paintings from his Budapest, Vienna, Bratislava, and Paris palaces and countryside castles.

Arriving at the Szépművészeti, simply “Szépmű” for locals, is a festive experience. From the city center, you saunter down the elegant Andrássy Avenue or jump on the charming underground M1 line, getting off at Heroes’ Square (the grand plaza filled with statues of Hungary’s greats, real or imagined). The museum’s entrance consists of a trio of Roman porticos. You take the middle one, elevated on a flight of stairs and supported by majestic Composite columns. All this is neo, of course – the building was completed in 1906.

There's a subterranean level full of antique sculptures, a ground floor with thematic Romanesque, Renaissance, and Baroque halls, but I'm here to draw your attention to the superb old masters paintings, which are upstairs. I highlighted below some of my favorites with a short profile on each, but you can also just roam the museum’s august halls, relying on the informative wall texts.

Keep an eye out for the Szépmű’s ambitious temporary exhibitions, which recently included shows on Bosch, Matisse, El Greco, and Renoir. Any gift shop? Of course! Café? Below-ground level! Just don't make the mistake of going on a Monday, because you'll find the oversized oak doors firmly shut. Final note: If you live here or planning more than one visit, consider buying the annual pass for HUF 9,800 (€25).

1. The Coronation of the Virgin, by Maso di Banco (1328/1330)

Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337) was one of the most important painters in history; he plucked Western Art from its Byzantine traditions and laid the foundations of naturalist painting, which is to say, rendering real-looking humans in real-looking places. For a truly immersive Giotto-experience, one must travel to Padova's Scrovegni Chapel, but even in Budapest it’s possible to get a taste of Giotto’s brilliance through his most talented pupil, Maso di Banco (? – 1353).

The Coronation of the Virgin by Christ, a popular apocryphal story at the time, shows Maso’s solid understanding of spatial depth and movement – most of his contemporaries would have struggled to place the crowd of angels around the throne looking so life-like and three dimensional, not to mention those playing music. But my favorite thing about this painting is the beautifully Giotto-esque faces of the angels: solemn, almond-eyed, bronze-skinned, and same-looking.

2. The Man of Sorrows, by Giovanni Santi (1490)

Giovanni Santi (1435-1494) was the father of a much more famous Santi – Raphael – which is why he’s usually put on the backburner. But the fact that Giovanni was the court painter at Federico da Montefeltro’s Ducal Palace in Urbino, a leading renaissance center in 15th-century Italy, is proof that he was a serious artist himself (it was at the Montefeltro court that the young Raphael picked up his immaculate manners which served him so well in his dealings with Popes).

The painting depicts a sorrowful Christ, risen from the dead, with his wounds from the Crucifixion still bleeding. The two dainty angels on his side show that Santi was familiar with the gracious manner of Perugino, a leading painter from nearby Umbria. That fly on Christ’s chest? A symbol of life’s impermanence, and a long-held painterly tradition to parade one’s talent by rendering the insect so realistic that a viewer would feel the urge to flick it off the canvas (please don’t do that).

3. Virgin and Child Enthroned, by Carlo Crivelli (1476)

Carlo Crivelli (1430-1495) had a strange, idiosyncratic, highly personal style that’s hard to categorize or pigeonhole. Despite a flawless technique for perspective and architectural details (as seen above), his mindset was more Byzantine and Gothic than Renaissance. Crivelli prized religious piety above all, often in ways that seem exaggerated and unnatural for his time, likely a function of his provincial clients in the Italian backwaters of Marche where he spent most of his life.

His paintings are deeply textured and thick with gold leaf, sometimes even in relief, as with the ornaments on the Virgin’s beautiful velvet robe above. The oversized garland of fruit hanging over her head – a Crivelli classic – alludes to Christ’s passion and death. Originally a polyptych, the other panels of the altarpiece are held by the National Gallery in London.

4. Ill-Matched Couple, by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1522)

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) was a man of many talents: mayor of Wittenberg, real estate investor, and the leading painter of 16th-century Germany. Cranach is also known for his close friendship with the Augustinian friar whose 95 Theses turned Europe upside down: Martin Luther (this didn’t stop the prolific Cranach workshop from accepting commissions also from Roman Catholic clients).

After the Reformation, Cranach’s moralistic paintings became very popular, especially the “ill-matched couple” series, in which wrinkled old men and women are looking for love in the wrong places. Above, a toothless creep is fondling the breast of a sinuous young woman while she’s stealing money from his purse. Look to your left for another Cranach in reverse setup: old woman-young buck. There’s a crude, Gothic strain to Cranach’s works, which pay little heed to anatomy. Some people find this refreshingly addictive, others painfully antiquated. (Amazingly, the Renaissance-perfect Albrecht Dürer was Cranach's exact contemporary.)

5. Portrait of a Young Man, by Giorgione (1508-1510)

Despite a short life, Giorgione (1477-1510) was a very influential painter in Renaissance Venice, so much that Titian’s early works are completely under his influence. Giorgione always creates a poetic, wistful, longing mood. Both in landscape – as with his famous Tempest, at the Galleria dell'Accademia in Venice – and in portraiture, such as the painting above.

This enigmatic young man, whose identity is unfortunately unknown, is shrouded in a dreamy melancholy. Is he in love? Lovesick, perhaps? Who knows, but he’s surely feeling deep things, making the moon-gazing German Romantics of the early 1800s seem like heartless monsters. Very few Giorgione works have survived, so this one is an especially cherished possession of the Szépmű.

6. Virgin and Child with Saint Elisabeth and the Young Saint John and Baptist, by Bernardino Luini (1525/1525)

When Leonardo da Vinci moved from Florence to Milan for the second time (1508-1513), his presence completely upended the Lombard painting traditions established by Vincenzo Foppa. The Szépművészeti has an entire hall dedicated to Leonardo’s most prominent followers – Bernardino Luini, Marco d’Oggiono, Antonio Boltraffio, Andrea Solario. It’s amazing to observe all the recycled Mona Lisa-faces enveloped in mysterious greens and yellows.

Bernardino Luini (1480-1532) is usually regarded as the most talented of the bunch. The Virgin shown above holding the child can’t rival the delicate litheness of Leonardo’s Madonnas, but it’s a work that can stand on its own. Not like some others sharing the hall, for example a workshop painting whose Madonna resembles a Leonardo-caricature. (The room also holds a bronze statuette attributed to Leonardo himself.)

7. The Esterházy Madonna, by Raphael (1508)

Raphael (1483-1520), perhaps the most famous painter in history, had an unusual skill for composition, always gently leading the viewer’s eye to what mattered most. He also set the standard for female beauty in Western Art for hundreds of years. No one before him painted the Virgin Mary with such purity, loveliness, and noble tenderness as he. The Esterházy Madonna brings together these two qualities and it’s also notable for the fact that after this painting, once in Rome, Raphael’s style yielded to Michelangelo’s influence (and came: muscular figures! bright colors! frantic movements!).

Not so fun fact: in 1983, together with a few Giorgione, Tintoretto, and Tiepolo paintings, an Italian-Hungarian criminal group stole the Esterházy Madonna from the Szépmű. After a months-long international manhunt, the paintings were found in Greece, hidden in a suitcase inside a monastery.

8. Portrait of a Woman, by circle of Bronzino (1560)

Bronzino (1503-1572) was a portrait painter of the Florentine nobility; he did, for example, the finest portraits of Cosimo I de' Medici, always tactfully concealing the Grand Duke's severe strabismus. Bronzino, amusingly, showed the Tuscan rich and wealthy completely devoid of emotions and shrouded in pretension. Titian's way of plumbing the human soul? Searching for the character behind the royal mask? Of no interest to Bronzino and his circle of followers. And yet there's something irresistible in his highly polished colors, his exceedingly elegant figures, the jewel-encrusted clothing, the lascivious references.

9. The Three Graces, by Giovanni Battista Naldini (second half of 16th-century)

Mid-16th century Florence: the city’s golden era is ending, the art capital has shifted to Papal Rome and imperial Madrid. It’s that strange post-Renaissance, pre-Baroque period known as Mannerism, when painters exaggerated Michelangelo’s figures and tacked onto them Raphael’s overly precious faces. The greatest Mannerist exponents were Rosso Fiorentino, Pontormo, Bronzino, and their group of pupils.

One of those, Giovanni Battista Naldini (1537-1591), painted the wonderful picture above. We see three entwined goddesses, representing charm, beauty, and kindness. Cloaked in translucent white with elaborately braided hair, they dance away while Cupid floats overhead with caduceus in hand, ensuring peace and love.

10. Hercules Expelling the Faun from Omphale’s Bed, by Tintoretto (1585)

Tintoretto (1518-1594) was to Venice what Bronzino was to Florence: the 16th-century star painter of his city, laboring for the local aristocracy in a highly personal, Mannerist style. But while Bronzino’s pictures are polished and detached, Tintoretto’s are fast and loose and dramatic. His canvases lack a cohesive composition; they’re disorienting, with strange, diagonally placed figures shown in the dark or in bright light.

The painting above captures these peculiar qualities. We see Hercules kicking off his bed a faun, who mistakenly thought he would find there Hercules’s wife, not him. Servants have gathered around and appear to be watching the scene with mild amusement, but there’s tension in the air. Positively strange – trademark Tintoretto.

11. The Preaching of Saint John the Baptist, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1566)

Following in the footsteps of Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569) was the famous genre painter of Flemish peasants. Using the pretense of a Biblical theme – Saint John the Baptist preaching – Bruegel is plying his regular trade here. The figures of Saint John and Jesus hardly stand out of the dense crowd, whose members are the centerpiece of the painting.

It’s worth spending a few moments observing the faces from close-up. All dimwits and halfwits, hardly a regular looking fellow. They’re gazing at the preachers in awe, in wonderment, in confusion, or some combination thereof. My favorites are the tree huggers, and the man who has a fortune teller read from his palm during the sermon. Bruegel’s bourgeoisie urban clients likely got a real kick out of the mocking of the lower classes. (There’s more of this kind of stuff at Vienna’s KHM, the pilgrimage museum for Bruegel fans.)

12. The Annunciation, by El Greco (1600)

The Crete-born El Greco (1541-1614) spent his formative years in Venice, which is why Tintoretto’s loose brushstrokes and elongated figures are never too far from his own. After failing to get work in Papal Rome and in King Philip II’s Madrid, El Greco settled in 1577 in Toledo, the ecclesiastical center of Spain filled with churches, monasteries, and religious foundations that kept him busy for the rest of his life. The cultured El Greco knew his Bible and knew what would sell in Counter-Reformation era Spain: legible scenes conveying their religious fervor even to an illiterate Spanish peasant.

Such as the Annunciation seen above, in which a yellow-robed Archangel Gabriel appears amid an illuminated sky to tell the obediently Bible-reading Virgin Mary that she would conceive a child who will be the son of God. Centuries later, painters such as Picasso, Max Beckmann, and Oskar Kokoschka hailed El Greco as a proto-modern, who rightly rejected naturalism in favor of the spiritual and the expressionistic. With five paintings, the Szépmű has the greatest collection of El Grecos in Europe outside of Spain.

13. Tavern Scene with Two Men and a Girl, by Diego Velázquez (1619)

One of the all-time greats, Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) spent most of his adult life as Habsburg court painter for King Philip IV of Spain, so naturally his greatest works today hang at the Prado in Madrid and the KHM in Vienna (lots of family portraits to facilitate those incestual marriages between the Spanish and the Austrian sides). The Szépmű too does have a stunning Velázquez, from when he painted genre scenes in the taverns of Seville (bodegones) as a twenty-year-old.

This early work shows the Caravaggian influence in its use of light and shadow, but the signs of Velázquez’s genius are already present. He elevated the tavern genre into high art the way he captured the banal details and the human character. We can almost smell the freshness of that crisp linen tablecloth. And how brilliant is the concentrated face of the girl pouring the wine and the way the liquid lands in the glass?

14. Penitent Mary Magdalene, by Gerrit van Honthorst (1625)

The Dutch Gerrit van Honthorst (1592-1656) spent his formative years in Rome where he completely fell under the spell of Caravaggio’s extreme use of light and darkness (in Italy, he’s still referred to as Gherardo delle Notti, “Gerard of the nights,” because he painted so many nocturnal scenes). In 1620, van Honthorst returned to his hometown of Utrecht and together with two other Rome-steeped Caravaggio disciples, Hendrick ter Brugghen and Dirck van Baburen, disseminated the new painterly style which came to be known as Utrecht Caravaggism.

We can identify Mary Magdalene by the vessel of oil to her left which she used to anoint the feet of Jesus. Using a rosary, she’s engaged in passionate prayer. So deep is her guilt about the sinful life she’s led as a prostitute that we see tears rolling down her rosy cheek. Her dark shadow on the wall enhances the striking white of her exposed skin. “Cow-eyed blondes,” is how the art historian Simon Schama referred to van Honthorst’s women from this period.

15. Wedding Portrait of Princess Mary Henrietta Stuart, by Anthony van Dyck (1641)

People don’t usually get excited about royal portraiture from days of yore because to our eyes these paintings often lack “truth” and the “real self” and seem overly flattering of their subjects. But if you accept that portraits of the high-born were basically improved public masks, modifications of the truth, then it’s possible to savor the best ones, such as those by Diego Velázquez and Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641).

The painting above shows van Dyck’s 1641 wedding portrait of Princess Mary Henrietta Stuart, who, at the age of nine, married the prince of Europe’s wealthiest country, the Dutch Republic. The Flemish van Dyck, Rubens’s most gifted pupil, spent the last decade of his life in London as a star painter flooded with royal commissions. His technical brilliance was astounding. Observe the mastery of details in the princess’ wedding dress: her delicate white lace collar, the glittering diamond brooch, the gentle ribbons, the folds in her rich silk wedding dress. We can almost feel the texture and weight of all the fabrics.

16. Still Life with Ham, Nautilus-cup and Silver Decanter, by Willem Claesz Heda (1654)

Golden-era (17th-century) Dutch still lifes are among the strangest of all paintings, showing tables piled with half-eaten foods and fancy tableware. What’s the point? The Netherlands were the richest country in Europe then and its citizens naturally wanted to flaunt their new-found capitalist wealth and prosperity. But it was also a pious, deeply protestant land, so a bit of moralizing was never too far – reminders about self control and our inevitable mortality. These two motivations merge in the brilliant works of Willem Claesz Heda (1594-1680), who, together with the fellow Haarlem-based Pieter Claesz, revolutionized the genre.

The burned-down candle checks the box for the obligatory memento mori, but Heda has more fun surveying the luxury items. Take a look at the beautiful nautilus shell with silver mounts, the salt container chock-full of salt grains, the polished ebony handle of the knife dangling off the table, the glistening fat on that piece of ham. The detail of surfaces and their reflections are startling. That spiraling peel of the lemon, imported by the Dutch East India Company along with other exotic produce from East Asia, was Heda’s way of showing off his draftsmanship.

17. Interior of the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) in Haarlem, by Pieter Saenredam (1653)

The Dutch Golden-era master Pieter Saenredam (1597-1665) was known for his exacting paintings of church interiors. He’d make detailed drawings and study the architecture plans before picking up the brush. The light-filled, peaceful halls belie the violent cleansing that had taken place inside these churches a century earlier, when the more zealous members of the Protestant community smashed the statues, stripped the paintings, broke the stained glass, and whitewashed the frescoes.

I’m among those who find Saenredam’s matter-of-fact style enthralling. His precise, detached, wistful manner has a lyricism, not unlike Giorgio Chrico’s deep perspective views of Italian cities from a few centuries later.

18. Brothel Scene, by Jan Steen (1668)

Perhaps no one did the Dutch moralizing genre scenes better than Jan Steen (1626-1679). His boisterous images of life in the city of Leiden convey straightforward ethical messages: too much drinking leads to foolish behavior; a messy home sets a bad example for the children; quacks pretending to be doctors are ridiculous charlatans. He’d often include himself in the paintings as one of the corrupt characters. Moralizing though they were, Steen’s paintings are technically brilliant and a lot of fun to try to decode.

Above, we see a coquettish courtesan comfortably lying back on a sofa with wine in hand while her prospective client is settling the price with the brothel keeper. Signs of sex abound: the hole on the foot stove, the dog’s position, the shape of that pitcher, the lute hung on the wall. But Steen warns us about the dangers of seeking physical pleasures in the brothel. The painting within the painting shows a young man being chased out of a building and the glass ball strung from the ceiling is a symbol of the fragility and transient nature of life, which, we're reminded, shouldn’t be wasted on carnal pleasures.

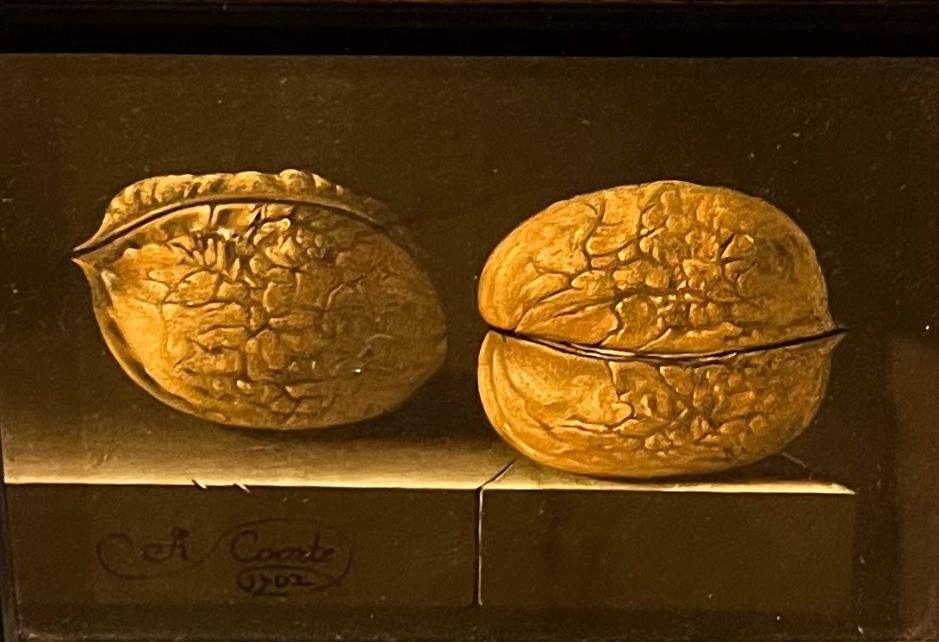

19. Two Walnuts, by Adriaen Coorte (1702)

As seen with Willem Claesz Heda above, Dutch still-life painters maintained astonishingly high standards of craftsmanship. Unlike the showman Heda, however, Adriaen Coorte (1665-1707) specialized in small-scale works depicting simple produce placed on a stone ledge: a bowl of strawberries, a bundle of asparagus, or, in this case, two pieces of walnuts. The simplicity of the scene belies its mastery. Bathed in light and set before a dark background, the walnuts appear as realistic as in a photograph and you're just about to reach for them. Spend a few moments before the picture and its intensity will gradually reveal itself.

20. St James the Greater Conquering the Moors, by G.B. Tiepolo (1749-1750)

Saint James, one of the twelve apostles, enjoys a hero's cult in Spain thanks to a legend that he led the Christian army to victory over the Muslims in the battle of Clavijo (844). Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770), the great Venetian Baroque painter, was the perfect man for the job to depict this momentous and completely fabricated event.

Tiepolo's monumental canvases embody the decadent twilight years of the Venetian Republic – bright and heroic, with an "epic breadth of the grand manner," as the art historian Rudolf Wittkower put it. What came from Tiepolo's loose and rapid brush here feels both joyfully superficial and deeply intense, featuring his typical zigzag composition (follow the line from the sword on the ground to the cherubs up top). Note that this picture is located in the Baroque Hall on the ground level and that there are smaller Tiepolo oil studies on the second floor.

21. The Water Carrier, by Francisco Goya (1808-1812)

As court painter for the Spanish King Charles IV, Francisco Goya (1746-1828) painted countless portraits of the Spanish aristocracy. These official works show the hand of a fluent and practical artist who knew how to tailor an image to fit what was expected by patron or sitter.

Starting in the late 1790s and with the onset of the brutal war between Napoleon’s France and Spain (1808-1814), Goya’s routine neoclassicism gave way to something harsher and more expressive. He became openly critical of the country’s backwardness, but also memorialized the heroic behavior of the Spanish independence fighters, such as the girl shown above, who’s bringing water to her compatriots on the battlefield. The free brushstrokes, the visible splotches of paint on her clothes, and the low angle view all enhance her sense of effortless confidence.