So much beauty contained in a single building.

There are countless reasons to visit the Kunsthistorisches Museum, known as the "KHM” locally. It’s Vienna’s greatest and grandest museum, inside Vienna’s greatest and grandest building, designed by Gottfried Semper (Emperor Franz Joseph had the German star architect move from Zürich to Vienna in 1869 for the commission). The museum’s source of pride is the old masters collection, accumulated by two art-loving Habsburgs: Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612) and Archduke Leopold Wilhelm (1614-1662), who was governing the Spanish Netherlands.

A visit to the KHM isn’t just about the art. The creaking parquet floors and the blue velvet-upholstered couches – I’ve seen people marvel, read, work, and nap on them – are as much fixtures of the place as Tintoretto’s Man with a White Beard (the portrait that inspired Thomas Bernhard’s laugh-out-loud bitter novel, Old Masters).

Ascend the main staircase – passing Antonio Canova's knee-bucklingly beautiful marble Theseus at the landing – to reach the painting galleries: Italian and Spanish on your left; Flemish, Netherlandish, and German on your right. In between, under the tall dome studded with royal statuary, is a fancy café. Entry to the museum costs €21 per person, but if you’re here for longer, consider purchasing the annual pass for €53. The best investment I've made this year.

Italian & Spanish Painters

Madonna del Prato, by Raphael (1506)

This is your chance to spend private time in an uncluttered hall with Raphael (1483-1520), one of the most beloved painters on earth and the person who set the standard for female beauty in Western art for hundreds of years. The painting of the Virgin with the child and John the Baptist shows Raphael’s famous gift for composition – Mary’s diagonally placed right leg completes the pyramidal structure of the three figures, who are placed in an enchanting pastoral scene, evoking harmony and bliss far into the distance. The painting is from Raphael's Florentine period (1504-1508), before he went to Rome and adopted Michelangelo's dynamic and muscular figures.

Bow-carving Amor, by Parmigianino (1534-1539)

Parmigianino (1503-1540), from the generation after the high renaissance masters, had an exceedingly elegant and graceful "mannerist" technique inspired by Raphael. This one is a charming depiction of Amor, the god of passionate desire, who innocently looks over his shoulder while carving his bow. He carelessly placed his weapon of erotic love on top of two books to convey its power over learned knowledge. Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612) was such a fan that he not only purchased the painting from his uncle, King Philip II of Spain, but also had his court painter, Josef Heintz, make a copy of it.

Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, by Parmigianino (1524)

This playful object shows off Parmigianino’s technical brilliance and self-confidence. The twenty-year-old painter made his talisman for Clement VII, the Medici pope and patron of the arts, when he set off from his hometown of Parma to find employment in Papal Rome. Parmigianino painted his own reflection in a mirror onto a small piece of curved wood. Our attention is drawn to the foreground, to the inflated right hand, as if he were to say, "Hey, watch this, my secret weapon, the source of my genius." (As for so many artists, Parmigianino's stay was cut short by the 1527 Sack of Rome.)

Susanna Bathing, by Tintoretto (1555-1556)

The Old Testament story of Susanna – two old men spy on the bathing lady, try to seduce, then falsely accuse her – takes us to the strange world of Jacopo Tintoretto (1518-1594). A star artist of golden-age Venice in the 16th-century (behind Titian, and beside Paolo Veronese), Tintoretto painted colossal “mannerist” figures who are always in frantic motion and burst with energy. Susanna is illuminated in radiant light and appears exaggerated compared with the creeps hiding behind the hedge. The bald man is about to fall off the canvas so unbalanced is the composition. The unusually long perspective makes the painting even more disorienting.

The Raising of the Youth of Nain, by Paolo Veronese (1565/1570)

Paolo Veronese (1528-1588) is known for his immense, theatrical scenes of which more than a dozen appear on the walls of the Kunsthistorisches Museum. Veronese was always drawn to the surface level; no matter the task at hand, he most enjoyed painting fashionably dressed Venetian aristocrats having a good time. Once he ran into trouble with the Inquisition for depicting "jesters, drunks, Germans, and midgets" on a Last Supper.

This one, ostensibly, shows the Biblical story of Jesus raising the dead son of a widow. The boy’s pale figure hides in the lower-left corner while our attention is directed to his beautiful mother at the center of the canvas, rendered in a wonderful light-blue silk dress. The robes of Christ, pastel pink and pastel blue with a metallic sheen, exemplify what's usually meant by "Venetian color" in painting.

Jacopo Strada, by Titian (1567-1568)

Few museums can boast 22 (!) paintings by Titian (1488-1576), one of the greatest of all. Many of these works aren't Titian's best, but I'd like to draw your attention to the portrait of Jacopo Strada shown above. Titian knew how to flatter his patrons – conveying their social status through elegant clothing – but also revealed their personality traits unlike anyone before Rembrandt.

A successful art dealer, including Titian’s, Strada was an immensely wealthy man as shown by his gold chain (with a medallion of Habsburg Emperor Maximilian II), fur cloak, and glinting sword. Titian’s brilliance: Strada’s mysterious sideway glance. People have long speculated whether this refined man perhaps harbored a bit of malice, too.

Nymph and Shepherd, by Titian (1570/1575)

In the 1570s, when Titian (1488-1576) was past eighty, he painted with a free and expressive brush. His late-period canvases have a loose and sketchy style, often imbued with a raw, violent energy. Above, a young shepherd is playing his flute to a woman who turns her back to him. The dark pastel colors and the restless pastoral scene are deeply unsettling, perhaps to evoke the shepherd's troubled state of heart.

Inspired by Titian, this rougher style – observe those two incredible red lines indicating the setting sun – was later adopted by both Velázquez and Rembrandt. Amusingly, art teachers often warn their students against imitation, arguing that in unskilled hands this technique leads to embarrassing failures.

David with the Head of Goliath, by Caravaggio (1600-1601)

Caravaggio's mystical naturalism and aggressive use of light and shadow revolutionized painting, leaving behind the Mannerist artifice exemplified by the likes of Parmigianino (see above). The brightly lit figures set against the darkness are often completely undignified and everyday-looking and hence relatable to viewers then and now. By the first half of the 1600s, countless Caravaggio schools sprouted both within and outside Italy, including the famous Utrecht School in the Netherlands.

Above, we see David, the dirty-nailed and unpolished shepherd boy he might have been, confidently but not boastfully showing the decapitated head of Goliath (to Saul, the King of Israel). Caravaggio did a more somber version of the subject a few years later, which is at the Gallery Borghese in Rome.

Infanta Margarita in a Blue Dress, by Diego Velázquez (1659)

It was a long-held tradition between the Spanish and Austrian branch of the Habsurgs to marry within the family (a result of this inbreeding: the famous Habsburg jaw, of which you can find plenty of examples in the Kunstkammer on the ground level of the museum). Family portraits would be dispatched from Madrid to Vienna and back to facilitate nuptials. This painting of Margaret Theresa, daughter of the Spanish king Philip IV, shows why the court painter Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) is regarded among the great in history.

We can almost feel the weight and texture of Infanta Margarita's gorgeous blue dress despite the loose brushstrokes, while her gaze reveals the individual behind that obligatory royal mask. Fun fact: Margarita is the same person who appears at the center of Velázquez's most famous painting, Las Meninas (in the Prado). Not so fun fact: she married Emperor Leopold I, moved to Vienna in 1666, and inspired his husband to expel the Jewish community from the city and knock down its synagogue.

Saint Michael Vanquishing the Devils, Luca Giordano (1664)

Many fans of the Italian Baroque believe that the Neapolitan school was unrivaled. Its pioneer, Luca Giordano (1634-1705), incorporated the best of the previous epochs and his epic paintings are always lively and betray his brilliant draftsmanship. Above, we see Archangel Michael effortlessly squashing the recalcitrant angels of heaven. Giordano rendered the rebellious Lucifer and his allies so repulsive that the painting – I’ve seen it time and again – never fails to elicit reaction from visitors. The topic of Lucifer’s expulsion from heaven was popular during the Counter-Reformation, being a symbol of Catholic victory over Protestantism. Little surprise that this oversized canvas landed in a Vienna church.

Centaur Chiron and Achilles, by Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1695/1700)

The Bologna-based Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665-1747) practiced a different type of Baroque than was common in 17th-century Italy. He freed himself from the tiresome grand manner, the cliched, similar-looking Biblical scenes – no matter what he painted, it's filled with a sincere feeling, rendered with a free brush and with a strong contrast of light and shadow.

The scene above is from the education of the young Achilles, who in Greek mythology was entrusted to Chiron, the wise centaur and teacher of heroes (hence the book and the armillary sphere in the lower left corner). Even with his eyes completely black, we sense the loving and tender care that Chiron directs to the young boy, whose expressive face is characteristically Crespiesque. Crespi was a painter’s painter – less appreciated by the public than by artists and art historians (Giorgio Morandi, the greatest painter of 20th-century Italy, adored Crespi).

The Freyung in Vienna, by Bernardo Bellotto (1759-1761)

Even if you don’t live in Vienna, the grand topographical cityscapes (vedutes) of Bernardo Bellotto (1720-1780) are a joy to observe. These highly detailed, factual paintings depict the Habsburg capital under Empress Maria Theresa. A day at the Schönbrunn Palace; the views from the Belvedere; the busy market in the Freyung district shown above, and so on. The clarity, the aggressive use of light and shadow, the brilliant draftsmanship, and the multiple perspective views (to pack more details) are all Bellotto's signatures. Also note the miniature citizens, made in a Rococo-style, who throng Bellotto's canvases: carriage drivers, priests, farmers, Habsburg bureaucrats.

The KHM has eight paintings by Bellotto, who was a nephew of the most famous Venetian vedute master, Canaletto (Bellotto, confusingly, referred to himself also as Canaletto to capitalize on the name). Bellotto left Italy in 1747 and spent the rest of his life as court painter in the north, in Dresden, Vienna, Munich, and Warsaw.

Emperor Joseph II with Grand Duke Leopold, by Pompeo Batoni (1769)

This carefully staged composition presents two young Habsburg Archdukes, sons of the reigning Empress Maria Theresa. As was customary among the nobility in the age of Enlightenment, Joseph and Leopold went on a cultural Grand Tour of Italy and had a double portrait painted by the most famous portraitist in Rome, Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787). The Saint Peter’s Basilica and the Castel Sant’Angelo help us identify their location, but there’s more to tell us.

Joseph, the heir apparent and already Holy Roman Emperor at this point, is casually leaning on a sculpture of Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, while pointing to a copy of Montesquieu’s The Spirit of Law (De l'esprit des lois). We are made to understand that here stands an enlightened ruler who embraces not the Baroque formalities but the most progressive political theories of his time. Indeed, Joseph went on to become an atypical Habsburg ruler (his brother, later also an emperor, was similarly reform-minded but more diplomatic).

Flemish, Netherlandish, and German Painters

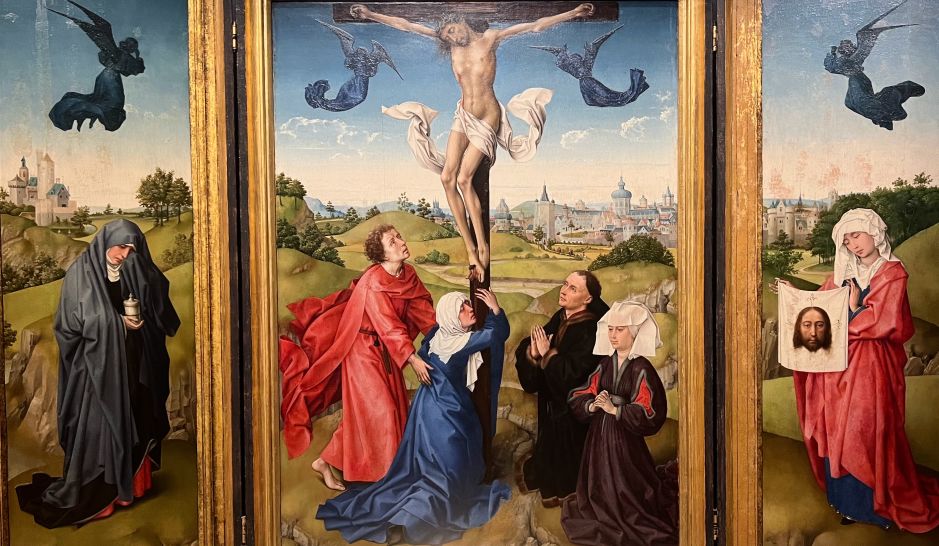

Crucifixion Triptych, by Rogier van der Weyden (1440)

This crucifixion of Christ is by Rogier van der Weyden (1399-1464), the leading painter of 15th-century Netherlands beside his slightly older contemporary, Jan Van Eyck. Still in his lifetime, van der Weyden, who worked in Brussels, was a celebrated artist on both sides of the Alps. The painting exhibits a mix of Gothic and Renaissance features. The unnatural folds of people's robes, the skeletal depiction of Christ, and the exaggerated expressions of the wailing Mary Magdalene and Saint Veronica are still in the Gothic mould.

What makes the picture pioneering for its time (1440)? The superbly detailed faces of Saint John the apostle and the patron, who is kneeling next to his wife on the right of the cross. The deep perspective views of the landscape and of the city of Jerusalem, which looks more like a medieval Flemish town. And the striking blue and vermilion colors that intensify the scene.

The Crucifixion, by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1500/1501)

Compared with the refined realism and technical brilliance of his contemporaries – Michelangelo, Dürer, Raphael – the paintings of the German Lucas Cranch the Elder (1472-1553) look strangely crude, anatomically flawed, and out-of-date. Still in the Gothic style. And yet Cranach’s canvases, especially his early works painted in Vienna around 1500, have an expressive power that’s hard to resist – just observe the tormented faces at the Crucifixion shown above.

Cranach later moved to Wittenberg as painter to the Saxon court, became friends with Martin Luther and, after 1517, a great advocate of the Protestant cause (this didn't stop his large workshop from working for Catholic clients too; he was a prudent Protestant). He put out hundreds of paintings and woodcuts in support of Luther and produced a popular moralizing series of "mismatched couples" in which old men and women are looking for love in the wrong places. You'll find many of these at the KHM, which has a great Cranach-collection.

Emperor Maximilian I, by Albrecht Dürer (1519)

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), the leading artist of the German Renaissance, was called the “Leonardo of the North” for his manyfold scientific interests and anatomical studies about human proportions. His paintings show little of the nervous brush and clumsy figures so typical in contemporary Germany, instead reflecting the solidity of Andrea Mantegna and the colors of Leonardo (the result of two extended trips to Italy).

The portrait above features the notorious Habsburg matchmaker and Dürer’s most important patron: Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519). The Caesar was so fond of his court painter that, according to an anecdote, he himself once steadied Dürer’s wobbly ladder while the master painted away up high. You’ll find Dürer’s famous signature hidden in the top right of the picture.

The Peasant Wedding, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1567)

Following in the footsteps of Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569) was another brilliant chronicler of Flemish peasants. More mocking than moralizing, Bruegel’s renditions of grotesque and dumb-looking villagers provided plenty of entertainment to his middle-class patrons.

Take your time to observe the ignorant faces in his best-known genre painting, the Peasant Wedding, in which a barn is the wedding venue, porridge the wedding meal, and paper crown the bridal jewelry. So mean! With its large figures and sharp diagonal composition, this late-period Bruegel shows the influence of contemporary Venetian Mannerism (see the similarities with Tintoretto’s Susanna above).

The Hunters in the Snow, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1565)

Twelve Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569) paintings hang in the Kunsthistorisches, making it the largest Bruegel collection in the world. Many know the Flemish master for his crowded genre scenes, as with the Peasant Wedding above, but he was also an astonishing landscape painter. The Hunters in the Snow is part of a series depicting life in the countryside during the various seasons.

A group of hunters with their dogs returns home; people set up a fire outside their house; ice skaters frolic on a frozen pond. But this isn't a happy place. The hunters are empty-handed and the sky has an ominous bluish-gray hue. Black birds are circling overhead. There's a palpable sense of foreboding amid the somber atmosphere. And look at that stunningly beautiful deep perspective view.

The Four Continents, by Peter Paul Rubens (1615)

The paintings of Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) aren’t easy to admire at first sight – exuberant canvases teeming with human flesh and floating putti. Things can get overwhelming from all the rhetoric. But Rubens was a genius – I realized this when I compared him to his Italian contemporaries – and the Kunsthistorisches has one of the biggest and best selections of his paintings in the world (based in Habsburg Antwerp, the tireless Rubens also served the court as its roving diplomat).

The picture above, the personification of the four continents and their four major rivers, shows Rubens at his best: muscular Michelangelo-esque figures, rosy-cheeked women, vibrant colors, tension and motion. High Baroque theater. Try to take it in and enjoy!

Self-Portrait, by Peter Paul Rubens (1638/1640)

A humanist intellectual who came of age at the Ducal Court of Mantua, Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) was more than just the leading painter of Catholic Europe. He felt as much at home in the classics (a reader would recite poems while he painted) as he did at the royal courts of Madrid, Paris, and London. While managing his enormous workshop in Antwerp, he found time to negotiate peace treaties on behalf of the Spanish Netherlands and to nurture his passion for collecting antiques. It is this dignified and somewhat worn artist-scholar-diplomat who peers down at us from this precious self-portrait (despite his immense output, Rubens painted only four self-portraits during his long career).

Large Self-Portrait, by Rembrandt (1652)

No matter what he painted – history, mythology, landscape, or portrait – Rembrandt (1606-1669) was most interested in the individual. Relying on just a few colors and the intense dramaturgy of light, he plumbed the soul like no one before him, seeking “human truth” rather than heroes or idealized beauty. Accordingly, this self-portrait is free of flattery and conventions – just look at that prominent root-vegetable nose of his. His clothes are dissolved by the dark background and we’re immediately drawn to Rembrandt’s illuminated face.

Who do we see? A man who’s tired and hurt and without illusions. But also proud and self-possessed, perhaps not yet done with life. Be careful with his penetrating eyes otherwise they might pierce a hole in your gut.

The Art of Painting, by Johannes Vermeer (1666-1668)

This Dutch Golden Age masterpiece is a precious possession of the Kunsthistorisches. The paintings of Vermeer (1632-1675), delicate, serene, and frozen in time, are often charged with allegorical meaning. Here, behind a drawn curtain, we see the back of an elegantly dressed painter – likely Vermeer himself – working on a portrait of the beautiful model standing before him. She is Clio, the muse of history and the inspiration of artists of the Netherlands, whose map is hanging on the wall. The mask on the table symbolizes imitation and hence the art of painting.

The technical virtuosity of the picture is astounding. Observe the creases of the map; the texture of the painter’s clothes; the red of his stocking, the blue of her robe; the black-and-white marble floor; and – a Vermeer signature – the soft light streaming from the left. (Bizarrely, Adolf Hitler bought the painting in 1940; after the end of the war, the Allies gifted it to Austria.)