From haunting Gothic churches to funky postmodern architecture, these are the most interesting buildings in Vienna.

As the capital of the Austrian branch of the Habsburg dynasty for more than 600 years (1278-1918), Vienna has a fascinating and layered architectural past. The city center (District 1) is best known for its Gothic churches and the Baroque winter palaces modeled after the Roman palazzo type. The Ringstraße, a spectacular boulevard separating downtown from the outer districts, appears in every architecture textbook as the prime example of historicist architecture of the second half of the 19th century. Perhaps these buildings – neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance, neo-Baroque, and so on – aren't so fashionable these days, but to most people the Ring remains the crown jewel of Vienna.

As a departure from this historicist style, the Secession group under Otto Wagner, Joseph Maria Olbrich, and Josef Hoffmann produced a unique brand of Viennese Art Nouveau around 1900. Soon, even this Art Nouveau looked dated compared with the modern architecture of Adolf Loos. Closer to the current day, Vienna has several globally renowned buildings, especially from the postmodern period of the 1970s and 1980s.

Note: Vienna's Architecture Center in the Museums Quarter has excellent permanent and temporary shows. In addition, the ground floor of the Ringturm also features exhibitions dedicated to Central and Eastern European architecture.

#1 - St. Rupert's Church (12-13th centuries)

Vienna’s oldest church still in existence is tucked away on a charming square, Ruprechtsplatz, on the north side of the city center. This is also where the Roman military camp (Vindobona) was once based. The church is named after Saint Rupert (660-710), the Bishop of Salzburg, the city that likely funded its construction since Vienna didn't have its own Diocese until 1469.

It more or less retained its simple Romanesque look for more than a thousand years, although parts of it reflect Gothic and Baroque additions. The nave and the lower floors of the tower were built in the 12th century, and two of the stained glass windows – in the middle of the apse – are from the 13th (the others were installed in 1993). Free entry, opening hours vary. Location.

#2 - Maria am Gestade (14-15th; 19th centuries)

This might just be the quirkiest church you’ve been to! The Maria am Gestade (Maria at the Shore) derives its name from its peculiar location on the bank of the Salzgries, once an arm of the Danube River. This proximity to the river explains why the church nave is so narrow and why mainly fishermen came to pray here until the Salzgries dried out in about 1750.

Take note of the beautiful Gothic paintings inside and the church’s tall tower topped by a helmet-like structure with decorative crockets. The stained glass windows and the high altar area are from the 14th century, the nave from somewhat later, as evidenced by its more complex system of ribbed vaults. Today, the Maria am Gestade serves the Czech and Slovak-speaking Catholics of Vienna. Location.

#3 - Minoritenkirche (13-14th; 19th centuries)

The original Gothic details of this grand and perennially quiet Franciscan church near the Imperial Palace (Hofburg) are still discernible despite myriad later additions and alterations yielding its stacked, blocky look. The church spire was destroyed twice during Ottoman Turkey’s siege of Vienna in the 16-17th centuries and ultimately rebuilt with a flat top. Interestingly, a copy of Leonardo’s Last Supper decorates the side altar – it was commissioned by Napoleon when he ruled Vienna in 1809, later intended for the Belvedere, but being too big for it, ended up here. Free entry. Location.

#4 - Augustinian Church (14th century)

The solemn Augustinian Church was, ironically, the venue of Habsburg weddings, including those between Empress Maria Theresa and Francis I, Napoleon and his second wife, the Habsburg Marie Louise, and Emperor Franz Joseph and Sisi. Little of the (neo-)Gothic structure is seen from the outside because the 18th-century expansion of the neighboring Court Library enveloped the church.

The highlight of the inside is the pyramid-shaped funerary monument of the Empress’ favorite daughter (Maria Christina) made by Antonio Canova, the greatest sculptor of the Neoclassical period. Completed in 1805, Canova placed a procession of mourners, young and old, who are swallowed up by the dark opening of the tomb, thereby generalizing the idea of death. The figure of the blind old man with the cane is especially moving. (Canova's other major Viennese sculpture, Theseus slaying a centaur, graces the main staircase of the Kunsthistorisches Museum.) Free entry. Location.

#5 - St. Stephen's Cathedral (12-15th centuries)

St. Stephen’s is Vienna’s biggest and most famous church, the city's main symbol. Erected on the ruins of two medieval churches, the Gothic building’s ever-expanding size symbolized Vienna’s rising imperial ambitions under the Habsburgs in the 14-15th centuries (the old Romanesque front is still the main entrance). The south tower, completed in 1433, marks the highest point in Vienna; the northern one was never finished.

Highlights of the mystical inside include the wraparound late-Gothic pulpit with the four church fathers pictured above (1510-1515), the winged Gothic side altar (Wiener Neustädter) at the end of the the left aisle, a beautiful early-Baroque high altar made by the Pock brothers (1641-1647), and in the right aisle the red-stone tomb of Habsburg Emperor Frederick III, who helped create the Diocese of Vienna in 1469 with the St. Stephen’s as its cathedral. Free entry to most parts. Location.

#6 - Saint Michael’s Church (13th-15th centuries; 18th century)

The Michaelerkirche, located across from the Imperial Palace and dedicated to Archangel Michael, is a study in architectural styles: the neoclassical entrance portal opens to a Gothic nave whose ribbed vault leads to an amazing late-Baroque altar from 1781. As with other prestigious medieval churches, the floors and the walls are layered with the marble tombstones of the aristocracy, such as the Liechtenstein family (this was the secondary parish church of the Habsburg family after the Augustinerkirche, see above).

There are three memorable representations of Archangel Michael defeating Satan and the fallen angels: a statue atop the triangular pediment outside; a 1350 fresco to the right of the entrance; and the busy high altar itself. Free entry. Location.

#7 - Portal of the Salvator Chapel (1520-1530)

Renaissance architecture is so rare outside of Italy that any extant piece is treasured and often granted landmark protection status. This is the case also in Vienna, where the Renaissance legacy comprises a few building portals, such as the one fronting the Gothic chapel of Vienna’s old City Hall.

Technically more Mannerist than Renaissance, two composite columns jut out from the surface and frame the richly decorated entrance. The segmental pediment, with statues of Jesus and the Virgin, is flanked by two fully armored knights, brothers Otto and Haimo Haimonen, who founded the church in the 13th century. Today, the chapel belongs to Vienna’s Altkatholische Church, a denominational group formed by splintered Catholics who didn’t accept the papal infallibility doctrine of the Vatican Council of 1870. Location.

#8 - Palais Starhemberg (1667)

It’s a fact of life that Rome was the capital of the Baroque and that it took at least a century for the rest of Europe to catch up to Rome’s revolutionary church and palazzo architecture, complete with oversized scrolls, broken pediments, and playful window surrounds. In Vienna, an early Baroque bird was the town house of Konrad Balthasar von Starhemberg, a right-hand man of Habsburg Emperor Leopold I. A solid though generic palazzo, it takes up an entire block in Vienna’s old aristocratic corner on Minoritenplatz. The only information known about the architect is that he was of Italian origin. The current occupant is Austria's Ministry of Education. Location.

#9 - Jesuit Church (1623-1627; 1703-1705)

The modest facade of Vienna’s main Jesuit church hides a glamorous interior designed in 1703-1705 by a heavyweight of the high-Baroque: Andrea Pozzo (1642-1709). Emperor Leopold I brought the Jesuit priest-artist from Italy, where he is best known for his illusionistic (quadratura) frescoes in Rome's Sant'Ignazio church. Here too, he painted a deceptively real-looking dome on the ceiling.

As an example of the theatrical Baroque, each of the eight side altars obtain light from a hidden cupola, mirroring the idea first developed by Bernini. The gorgeous details include the wooden inlays of the pews and their convex shapes that sync with the hemispherical galleries up top. The pink-white color scheme with gilded details lends a joyful atmosphere to the church, whose altar paintings were also made by Pozzo’s workshop. Free entry. Location.

#10 - Kirche am Hof (14th century; 17th century)

The Kirche am Hof wins the prize for the most unbridled Baroque facade in Vienna. There’s hardly any wall space left amid the projecting and receding bays, stacked double and triple colossal pilasters, broken pediments, and oversized scrolls. Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand I gave the church to the Jesuits, who launched their Counter-Reformation crusades from here in the 17th century. The terrace wasn’t used just for benedictions, but also to stage their didactic theater plays. Since the Jesuits already managed the university church of Vienna, this one came to be known as the “Upper Jesuit Church.”

Inside, there’s a thrilling display of stylistic eclecticism: Gothic ribbed vaults and piers mix with Baroque chapels and Corinthian capitals. Amazingly, the choir and the high altar were overbuilt in a Neoclassical style, complete with a coffered barrel vault. In 1782, Pope Pious VI gave a blessing from the balcony, as did Pope Benedict XVI in 2007. Today the Kirche am Hof belongs to the Archdiocese of Vienna and serves the city’s Croatian Catholic community. Location.

#11 - Liechtenstein City Palace (1691-1705)

In 1690, Italian architect Domenico Martinelli (1650-1719) moved to Vienna to give a taste of Roman Baroque residential architecture in the Habsburg capital. The Liechtenstein family’s sober but monumental city palace – it takes up an entire block – shows many similarities with Bernini’s Palazzo Chigi-Odescalchi in Rome from a few decades earlier: a central projection accented with colossal pilasters, a powerful cornice topped with an open balustrade carrying statues. Evidently, this type of classical Baroque style was dear to the head of the Liechtenstein clan, Johann Adam Andreas, as he had Martinelli design his garden palace too in today’s District 9.

Adolf Loos was a fan of the building; I'll now pass the mic on to him: "The most beautiful town house ... Here we hear the mighty voice of Rome, unadulterated, without the scratchy background noise of a German gramophone. Go from Minoritenplatz along Abraham a Sancta Clara Gasse and lift up your head to the portal of this building." Location.

#12 - Eugene Savoy’s Winter Palace (1695-1724)

After the final defeat of Ottoman Turkey in 1683, a sense of optimism filled Viennese society, resulting in a frenzy of building activity. The go-to architect of the Habsburg Court and the aristocracy was Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach (1656-1723), an Austrian who spent 16 years working in Rome for a subcontractor of the great high-Baroque masters, Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona.

Fischer von Erlach designed the winter palace of Prince Eugene of Savoy, the military general who routed the Ottoman army. Inspired by Italian examples (Palladio's Palazzo Valmarana or Bernini's Palazzo Chigi-Odescalchi), he used giant pilasters across two floors to offset the horizontally stretched building tucked away on this downtown side street. Elaborate reliefs frame the three beautiful entrance portals and draw parallels between the heroic deeds of the Prince and those of Hercules, Perseus, and Aeneas. Also note the playful window surrounds on the upper level. The inside can’t be visited; the building has long been home to the Austrian Ministry of Finance. Location.

#13 - Plague Column (1694)

The Habsburg ruling family relied on the Baroque as a propaganda tool to express their power and religious devotion. When the 1679 plague ended, the famously pious emperor, Leopold I, ordered that a column be erected on Vienna’s main square, the Graben. Covered in blobs of white cloud and upbeat angels, the obelisk-shaped monument is impressively tall and dramatic. On its pedestal, we see Emperor Leopold, encircled by the coats of arms of his territories and successfully pleading to the golden Holy Trinity up top to save his people. The relief panels show scenes of the plague-ridden city.

The complex design of the plague column came from the imperial theater engineer Ludovico Ottavio Burnacini, the sculptor Paul Strudel, and architect Johann Fischer von Erlach. Location.

#14 - Peterskirche (1702-1733)

Strollers of Vienna’s main shopping street, the Graben, are often too focused on the nearby Stephansdom to notice the Peterskirche, despite being one of the great Baroque churches of Austria. According to Viennese legend, Charlemagne founded a church here in 792, an event depicted in high relief on the southeastern facade. The outside: two onion-topped slanted towers sandwich the concave facade and its central dome – a symbolic union of the Austrian and the Roman Baroque traditions.

The gilded ornaments weigh (too) heavily on the interior, but focus on the masterpieces. The astonishing martyrdom of John of Nepomuk sculpture group across from the pulpit by Lorenzo Mattielli. I’d love to see Johann Michael Rottmayr’s ceiling fresco of the Coronation of the Virgin restored (he frescoed the dome of the Karlskirche too, now all polished). Antonio Galli Bibiena, from the famous Italian family of Baroque stage designers, sketched the high altar and the quadratura fresco above the choir. The Peterskirche is currently managed by the priests of the Opus Dei. Location.

#15 - Karlskirche (1716-1737)

Vienna’s main Baroque church was also designed by the Rome-trained Court Architect, Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach (1656-1723). It’s as if he tried to showcase his Italian education: two Tranjanesque columns frame the classical entrance portico, which is connected to the towers by concave wings, similar to Pietro da Cortona’s Santa Maria della Pace in Rome and Filippo Juvarra's Basilica of Superga in Turin. A beautifully elongated dome soars above the central plan.

The carvings on the columns show scenes from the life of Charles Borromeo (1538-1584), the counter-reformationist Archbishop of Milan and patron saint of the reigning Habsburg Emperor, Charles VI (1685-1740). The columns are also a memento to Habsburg Spain, which had just been lost to the Bourbons.

The oval-shaped inside features high-Baroque ebullience: undulating gilded surfaces held together by a prominent red marble entablature. Both Johann Michael Rottmayr's fresco and the dramatic high altar – golden rays and stucco clouds lit from a hidden cupola – depict Saint Charles's ascension into heaven. The side altars feature famous paintings, including the Assumption of Mary by the Venetian Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734). There’s an admission fee to enter the church with access also to the lookout point up top. Location.

#16 - Court Library (1723-1726)

Perhaps no part of the Habsburg Imperial Palace (Hofburg) is more striking than the Court Library on Josefsplatz, designed, as usual, by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach. The staircase, lined with classical remains as in a Roman palazzo, leads to the marble and wood-encased halls filled with 200,000 books, ranging in time from 1503 to 1820.

At the center rises the frescoed dome, a breathtakingly dynamic composition by Court Painter Daniel Gran (1694-1757). A bright blue sky unites the various scenes, which are a running commentary on the great work of the library's founder and reigning emperor, Charles VI, through typical allegorical-mythological figures (the touchscreen can help make sense of it all). Charles's marble statue stands proudly below the dome. Unlike the new wing of the library on Heldenplatz, this one (Prunksaal) is open to visitors with a €10 admission. Location.

#17 - Daun-Kinsky Palace (1713-1719)

The two architects – and arch-rivals – who defined Vienna's Baroque are Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach (1656-1723) and Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt (1668-1745). Their styles were similar to each other’s, both originating in Italy, more daring than the classical Baroque, but less so than the unbridled buildings of Francesco Borromini. Hildebrandt’s surface decoration was a bit more expressive and heavy-handed than that of Fischer von Erlach.

In addition to the Belvedere (see below), a good example is Hildebrandt's Palais Daun-Kinsky in Vienna’s city center. The powerfully projecting main entrance leads the eye to the family’s coat of arms above the first floor. The central axis features tapered columns and richly detailed window surrounds and pediments. Up top, the balustrade supports decorative armor and statues. The striking staircase is accessible, just don't let Carlo Carlone’s frescoes and all the flying putti give you vertigo. Location.

#18 - Belvedere Palace (1712-1723)

This immense two-part Baroque palace – Lower and Upper Belvedere – was built as the summer residence of Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663-1736). Apart from being a great field marshal, Prince Eugene was a patron of the arts and liked to lavishly entertain his famous friends, including Voltaire, inside the gilded halls packed with books and paintings (his painting collection today hangs in the royal palace of Turin, which purchased it after the Prince’s death). Modestly, the ceiling frescoes depict the Prince’s ascension into heaven and point to his resemblance to mythological gods. A mainly Italian group of artists – Martino Altomonte, Carlo Carlone, Daniel Gran, Lorenzo Mattielli – executed the stunning decorative program.

The terraced Baroque garden with clipped hedges offers panoramic views all the way to the Vienna Woods and beyond. Lukas von Hildebrandt’s masterpiece is a picture gallery today, best known for its Biedermeier paintings and Gustav Klimts, and as the location of the 1955 State Treaty was signed which re-established Austria's independence. €24 admission (advance ticket purchase). Location.

#19 - Schönbrunn Palace (14th-19th centuries)

What started as a hunting lodge on the Vienna outskirts gradually transformed into the Habsburg family’s enormous summer palace, known as “Vienna’s Versailles.” Empress Maria Theresa, who ruled from 1740 to 1780, lived here in Rococo style, surrounded by astonishing details such as the black lacquer panels and inlaid floors of the "Chinese Cabinets." Another enthusiastic occupant of the palace was Emperor Franz Joseph (1848-1916), but his study, where he toiled daily from five in the morning, seems relatively spartan in comparison.

Originally by Fischer von Erlach and Nicolo Pacassi, the building’s facade was tamed by architect Johann Aman during the neoclassical period (1818-1819) but retained its Baroque character. Parts of the vast garden include the “Roman Ruin” and the Gloriette pavilion (1775), typical neoclassical elements of the late 18th century meant to evoke the great empire. Admission tickets range €20-35, but the garden is open to the public. Location.

#20 - Fries-Pallavicini Palace (1783-1784)

One of the first neoclassical buildings in Vienna stands across the Imperial Palace, facing the equestrian statue of Habsburg Joseph II. The enlightened Emperor (1741-1790) must have been fond of the simple style, but not so the public: a scandal broke out over architect Hetzendorf von Hohenberg's unadorned facade and the building's owner, Earl von Fries, yielded to the pressure, hence that outsized Baroque central portal with caryatids carrying a broken segmental pediment. The story brings to mind Adolf Loos's later misadventures a block away. Fun fact: the palace is featured in The Third Man (1949) as the apartment of Harry Lime (Orson Welles). Location.

#21 - The old General Hospital, Narrenturm, Josephinum (1784-1785)

A growing population and the rationalist ideas of the late 18th century unleashed the demand for a modern public hospital instead of the haphazard and overcrowded places of the past. It fell to the enlightened Habsburg Emperor, Joseph II (1741-1790), to convert into a modern hospital what had been a home for disabled soldiers, expanding it with an eye-catching rotunda for the mentally ill (Narrenturm; 1784) and an academy training army doctors (Josephinum; 1785), both designed in early-classicist style by Court Architect Isidore Canevale. Since 1998, the old hospital grounds comprise the campus of the University of Vienna and the Narrenturm is home to an unsettling museum of unusual pathological diseases. Location.

#22 - Theseus Temple (1819-1823)

An ancient Greek temple right in Vienna's city center? Baseless Doric columns of shimmering white marble, a somber entablature complete with triglyphs and metopes capped by a triangular pediment – Peter von Nobile's work is a perfect copy, though reduced in size, of the 5th century BC Temple of Theseus in Athens.

The Viennese temple was built to house Theseus slaying a centaur, a beautiful marble sculpture by the superstar sculptor, Antonio Canova (1757-1822). Irony #1: The artpiece was commissioned by Napoleon, a Habsburg arch-enemy, and intended for the city of Milan. Irony #2: It turned out that the temple in Greece that served as a model for this one was falsely identified as the temple of Theseus. Irony #3: in 1890, the sculpture was moved to the nearby Kunsthistorisches Museum. Still, this lonely, emptied, and mistaken Neoclassical building continues to anchor the charming Burggarten. Location.

#23 - Outer Castle Gate (Äußeres Burgtor) (1821-1824)

Unlike his father, Leopold II, Habsburg Emperor Francis I (1768-1835) wasn't a very enlightened ruler, being terrified of French revolutionary ideas. Together with his chief advisor, Chancellor Metternich, they crushed all dissent and it's telling that the major construction during his reign, the new outer gate to the imperial castle, is dedicated to a military victory (over Napoleon in Leipzig).

The outside of the central gate resembles five triumphal arches, the inside, with baseless Doric columns, a Greek temple front (as with the nearby Theseus Temple, above, it's the work of architect Peter von Nobile). In 1934, the government created a monument for Austrian heroes inside the gate, which is currently under renovation. Location.

#24 - Stadttempel (1824-1826)

This is the only temple in Vienna that survived the Kristallnacht of November 1938, when Austrian Nazis set on fire dozens of synagogues (with this one, they didn’t want to damage the neighboring buildings abutting it). The elegant neoclassical synagogue emerges behind a nondescript facade in Seitenstettengasse.

The elliptical hall, designed by Josef Georg Kornhäusel, is raised on twelve Ionic stone columns with gilded capitals. Daylight enters through the lanterned dome. Today, the synagogue is still functional, albeit with a small congregation. Entry only with advance registration and part of a guided tour. Location.

#25 - "Biedermeier Row" in Mechitaristengasse (first half of 19th century)

Biedermeier is an umbrella term used to describe the art and architecture of the Habsburg Monarchy during the repressive years of Habsburg Emperor Francis I/II and Chancellor Metternich in the first half of the 19th-century. Initially a derogatory term, Biedermeier springs from the sober neoclassical style that’s been softened to appeal to the popular tastes of the growing (lower) middle class. Its most recognizable form is in furniture design and painting, but Biedermeier architecture also exists.

In Vienna, most Biedermeier buildings are located in Districts 7 and 8, just past the Ringstraße, where better-off artisans, shop-owners, and mid-level state bureaucrats lived. Neudeggergasse and Mechitaristengasse are each practically a Biedermeier row. These small, two-story houses feature gentle window surrounds, simple terracotta decorations, and often bring to mind the early Renaissance buildings of Rome, in miniature versions. Location.

#26 - Altlerchenfeld Parish Church (1848-1861)

An unfairly under-visited building in Vienna, the Altlerchenfeld church is a prime example of Romantic architecture and a special one at that! The church’s construction began in a predictable Neoclassical style but the revolutionary events of 1848 saw the young Swiss architect, Johann Georg Müller, take over the design plans. Müller, who found inspiration in Romantic notions of medieval architecture, grafted Romanesque portals with nested arches onto a basilica plan topped with an octagonal dome.

The inside is a study in vaulting techniques: saucer domes, barrel vaults, and ribbed vaults appear throughout, recalling the Byzantine, the Romanesque, and the Gothic. Professor Joseph von Führich oversaw the exhaustive fresco cycle, a rare example of the Nazarene style, which was a branch of Romantic painting – religious themes rendered in the style of Raphael – that peaked in the 1820s. Location.

#27 - Arsenal & Museum of Military History (1849-1856)

In light of the revolutionary events of 1848, the young and bellicose Emperor, Franz Joseph, decided to strengthen the Habsburg military with a new arsenal complex capable of weapons production and storage. One of the 31 newly erected buildings was the weapons museum, whose intent was to extol and glorify the Austrian military and its commanders.

This early work of architect Theophil Hansen (1813-1891) looks emphatically different from his later Renaissance architecture (see below) and embodies the Romantic style of the 1850s with its medieval, fortress-like elements, red brick, arched windows, and Byzantine dome. The building is still a museum today. Location.

#28 - Vienna Ringstraße (1860-1890s)

Much of Vienna’s current housing stock sprung up in the second half of the 19th century, when the city’s population rapidly increased during the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph (1848-1916). Most notable was the construction of the horseshoe-shaped Ringstraße between the historic city center and the suburbs, replacing the vast land taken up by the old city walls and glacis.

Starting in 1857, eye-catching revival buildings, such as the Court Opera shown above, appeared along this newly formed, 56-meter (184 ft) wide monumental avenue. The size and style of each building reflected the competing cultural and political values between state, church, and the emerging middle class.

As the period drew to a close, these historicist buildings were increasingly mocked as being out of date; still, there's a striking harmony to the Ringstraße. It takes about an hour to walk from one end (say from the Börse) to the other (Otto Wagner's Postsparkasse). You could also jump on one of many trams that passes through it. Location.

#29 - Vienna Ringstraße: Votivkirche (1854-1879)

After the unsuccessful 1853 assassination attempt of Emperor Franz Joseph by a Hungarian nationalist, the emperor's brother, Maximilian, started a fundraising campaign among Viennese citizens to build a church of gratitude. The fundraising and later the construction coincided with the increased influence of the Catholic church in Austria. After more than two decades, architect Heinrich von Ferstel's twin-towered limestone church soared high above its surroundings. Today, the Votivkirche is considered one of the grandest neo-Gothic churches of the 19th century (and sometimes mistaken for the medieval-Gothic St. Stephen’s cathedral). Location.

#30 - Vienna Ringstraße: Museum of Applied Arts - MAK (1866-1871)

Heinrich von Ferstel (1828-1883) was a skilled architect able to design in totally opposing styles; for example, his Gothic-style Votivkirche overlooks the classical university on the Ringstraße, also by him. He was criticized for lacking conviction and being a mere aesthete ("You need a Renaissance building? I can do one for you" kind of thing). Nonetheless, his red-brick museum of applied arts featuring sgraffito friezes and majolica medallions has been copied all across the dual Monarchy. Once here, be sure to see the collection featuring rare Thonet chairs and Wiener Werkstätte pieces. Location.

#31 - Vienna Ringstraße: City Hall (1872-1883)

In the golden era for secular politics in Austria – the late 1860s and early 1870s – the liberal party won major concessions from Emperor Franz Joseph. Together with its neighboring buildings, the Austrian Parliament and the University of Vienna, the City Hall symbolized middle-class constitutionalism and rationalism. They were a counterweight to the Imperial Palace (Hofburg), across the street, and the Votive Church (see above).

This secularized neo-Gothic structure – the ground floor rustication, the symmetry, the cornices all bring to mind the Renaissance – is the work of German architect, Friedrich von Schmidt (1825-1891). You'd be correct to observe parallels with the Hungarian Parliament: Imre Steindl (1839-1902), the designer of the Budapest building, was a favorite pupil of von Schmidt. Location.

#32 - Vienna Ringstraße: Austrian Parliament (1874-1883)

The House of Parliament expressed the rising power of secular middle-class politics in 1860s Austria. Architect Theophil Hansen's masterpiece used Greek-style classical culture as a symbol of the enlightenment this middle class advocated and the legislative power it finally attained from the emperor in 1866. Pallas Athena, the god of wisdom, stands proudly outside the portico, along with statues of ancient historians and horse tamers, all proclaiming the primacy of reason over emotions. With advance registration, the building can be visited for free as part of a guided tour. Location.

#33 - Vienna Ringstraße: Imperial Palace Extension & Court Museums (1871-1907)

No writeup about the Ringstraße is complete without Gottfried Semper (1803-1879). Emperor Franz Joseph invited the famous German theoretician and starchitect from Zurich to Vienna to help with the ambitious extension plans of the Imperial Palace (Neue Burg). Semper was going to connect the Neue Burg through triumphal arches across the Ringstraße to the duo of royal museums, the Kunsthistorisches and the Natural History.

Not all of it was realized, but the completed parts – the southern wing of the palace and the two museums – impressively convey Semper's theory that such theatrical backdrops are integral elements of urban life. That infamous balcony under the triumphal arch shown above is where Adolf Hitler in 1938 declared the annexation of Austria by Germany to the applause of tens of thousands of Viennese people. Location.

#34 - Vienna Ringstraße: Fine Arts & Natural History Museums (1871-1891)

Once more, Gottfried Semper, together with Carl von Hasenauer, created a monumental public square. An urban theater backed by the grand, decorative, neo-Baroque buildings of the Kunsthistorisches and the Naturhistorisches Museums. The buildings have a notoriously complex iconography, with each facade celebrating a different era in history (antique; medieval; renaissance; modern). Note the beautiful contrast between the rough-textured rustication of the ground floors and the smooth surface of the upper stories, and the dense but not overcrowded ornaments throughout.

The museums flank Maria-Theresien-Platz, at the center of which presides the throned statue of Empress Maria Theresa surrounded by major figures of the Austrian Enlightenment as well as her generals, diplomats, Joseph Haydn and even the young Mozart. Location.

#35 - Vienna Ringstraße: Burgtheater (1869-1888)

During his relatively short stay – three years – in Vienna, Gottfried Semper not only designed the new imperial palace and the court museums, but also the nearby court theater (together with local architecture professor, Carl von Hasenauer). The monumental building with a highly articulated exterior shows obvious parallels with Semper's Dresden Opera House.

Colossal pilasters span the convex central axis, which features highly decorated Venetian-Baroque arched windows. This block is topped by a giant frieze and a balustrade on which sits the statue of Apollo between the muses of drama and tragedy. Busts of famous playwrights appear on the facade. The building was badly destroyed in WWII bombings but rebuilt in its original form by 1955. Location.

#36 - Academy of Fine Arts (1871-1877)

Here’s my favorite by Theophil Hansen (1813-1891), the prolific architect who designed more buildings along Vienna's Ringstraße than anyone else. This is Hansen at his best: taut proportions, terracotta details and noble materials, clearly defined horizontal partitions – all details in control of the architect. The ambitious decorative program could reflect the influence of Gottfried Semper, who was in Vienna during this time.

It's worth glimpsing the inside, too, especially the main auditorium and the picture gallery on the top floor, which houses astonishing old masters paintings by the likes of Hieronymus Bosch, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt (€9 admission). On the Makartgasse side stands a granite memorial to Otto Wagner, who was the university's influential professor from 1894 to 1915. Location.

#37 - Vienna Ringstraße: Palais Epstein (1868-1871)

In addition to monumental public buildings, the Ringstraße features privately owned residential houses that look like Italian palazzos from the outside (this one is a combination of the Florentine and the Roman Renaissance styles). Behind the grand facades and staircases were private apartments aimed to maximize rental income for the owners. Many of these "rental palaces" were commissioned by wealthy Jewish businessmen, as with the most striking example, the Palais Epstein, located next to the Austrian Parliament (see above).

Theophil Hansen, also in charge of the Parliament, designed so many such apartment-house blocks that later, when anti-semitism in Austria was on the rise, he was mocked as the "architect of the Jews." Location.

#38 - Augustinian Bastion (17th and 19th centuries)

As mentioned above, modern Vienna no longer needed its old fortifications, bastions, ramparts, and moats. Starting in 1857, they were knocked down and leveled to make way for the Ringstraße and the glitzy buildings lining it. However, a few leftover elements of these defense structures still stand, most notably the ramp that led up to the Augustinian Bastion (the bastion itself is gone). That’s why the building of the Albertina Museum, which was built on the ramp, is elevated from the street level. Since 1869, the Danube fountain – personifications of the Danube and other rivers in Austria – complete the “bastion” which is still connected to the medieval city walls facing the Burggarten. Location.

#39 - Palm House Schönbrunn (1881-1882)

London’s Crystal Palace (1851) ushered in the era of glass and cast iron construction in Europe. For the next several decades, exposed metal frames filled with glass surfaces became all the rage, appearing as exhibition venues, train stations, market halls, department stores. And also, as seen above, as greenhouses, given their ideal light-permitting and heat-containing qualities.

Emperor Franz Joseph commissioned the 113-meter long complex inside the Schönbrunn gardens to make space for the ever-growing imperial plant collection. The palm house has three climatic zones to accommodate a range of plants, from the Mediterranean to the subtropical. Despite the modern building materials, the pavilions, which were designed by Court Architect Franz Segenschmid, are still in the historicist style (neo-Baroque). The Palm House is still functional and open to visitors. Location.

#40 - Stadiongasse 6-8 (1882-1883)

Beside Adolf Loos, Otto Wagner (1841-1918) was the father of Viennese modern architecture. To appreciate Wagner's evolution, we need to start with one of his first independent works: the Italian palazzo-like residential building on Stadiongasse, today home to the Colombian embassy. The classical vocabulary is still prominent – rusticated lower floors, windows framed by half-columns and intensely projecting entablature. But Wagner, even as a young architect in the early 1880s, never let his ornaments run wild. The facade looks taut, proportional, in perfect harmony. (Compare it with the building across the street from it.) Location.

#41 - Nussdorfer Dam & Bridge (1894-1899)

In 1894, Otto Wagner (1841-1918) won the commission to design the Viennese railway network (Stadtbahn), consisting of dozens of stations, bridges, embankments, tunnels, and viaducts across the city. Wagner employed more than 70 people at times for this massive project, which profoundly shaped his style toward a more functional architecture. His use of exposed iron trusses also dates back to this time. Wagner viewed the Nussdorfer Dam, which was meant to prevent flooding of the Danube Canal, as an entry gate to the city, hence the monumental treatment using pylons and lions. Location.

#42 - Secession Building (1898)

What’s this severe, windowless, strange white structure topped with a gold "dome" doing in the heart of Vienna? It’s the exhibition hall of Secessionist artists, the group that struck out on its own in 1897, leaving behind the conservative confines of the Association of Austrian Artists (Künstlerhaus). Gustav Klimt’s famous Beethoven Frieze from the 14th Secession exhibition in 1902 is still on display in the below-ground level.

The building, designed by the most talented of the young bunch, Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867-1908), features a collage of historical motifs: four pylons on top (ancient Egypt), gorgons above the copper door and the owl reliefs on the sides (Pallas Athena and Greek mythology), Art Nouveau decorations throughout. The gilded bronze leaves and the dome symbolically crown this new home of art.

Coined by the Hungarian art critic, Ludwig Hevesi, “To every age its art, and to that art its freedom (Der Zeit ihre Kunst, der Kunst ihre Freiheit)," says the inscription on the facade. The building functions as a museum currently. Location.

#43 - Majolica and Medallion Houses on the Wienzeile (1898)

Otto Wagner’s architecture for a short period was shaped by the Europe-wide Art Nouveau and the early phases of its local variant, the Viennese Secession. As mentioned above, the movement was formed in 1897 by a group that included Wagner’s young assistants – Joseph Maria Olbrich and Josef Hoffmann – who broke away from the Vienna Künstlerhaus after its president censored exhibitions by modern artists.

Wagner soon joined them, and the rich floral patterns adorning his Majolica House show the typical features of the early Viennese Secession (framed by iron and glass, the stores on the ground floor are more functional). The building next door – 38 Linke Wienzeile – is also by Wagner and known as the Medallion House because of its facade decorations by Koloman Moser. Location.

#44 - Karlsplatz Stadtbahn Station (1899)

Best-known of the Viennese railway network (Stadtbahn) are two dazzling Art Nouveau stations, both by Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867-1908). One of them at Karlsplatz, the other outside the Schönbrunn Palace made specifically for Emperor Franz Joseph, the Hofpavillion. The Karlsplatz pavilion shows parallels with the subway stations of Paris from this time: curvilinear frames in green, floral motifs, gilded ornamentation – a true crowd pleaser. Location.

#45 - Rüdigerhof (1903)

Rüdigerhof is a prime example of the later-period Viennese Secession style. The powerfully cantilevered cornice and the downward spiraling decorations of the top floor bring to mind Otto Wagner’s buildings. The architect, Oskar Marmorek (1863-1909), was an active Zionist and close friend of Theodor Herzl (he also suffered from depression and it's a well-known and tragic fact that he committed suicide on his father's tomb in Vienna's central cemetery). The lively café on the ground floor, Cafe Rüdigerhof, offers a good excuse for a visit. Location.

#46 - Portois & Fix House (1899-1900)

Architect and university professor Max Fabiani (1865-1962) designed several pioneering buildings across Vienna, Trieste, and Ljubljana. This one, for the upscale furniture manufacturer Portois & Fix, features unadorned glazed ceramic tiles produced by the Pécs-based Zsolnay. Fabiani had worked in Otto Wagner's office and the Majolikahaus, above, might have been an influence but the decorative program here is reduced to shades of green, the company's initials (upper left), and the construction year (upper right). The original portal with the company’s name, unfortunately, is no longer in place. Location.

#47 - Steinhof Church (1904-1907)

Otto Wagner’s famous church for the Steinhof mental institute is located on the Vienna outskirts. Wagner re-used an earlier plan for a Greek orthodox church, hence the Byzantine features with a central plan and lots of gilded details. He borrowed elements from Andrea Palladio’s church architecture, for example the thermal window (on the front), the tripartite windows (on the sides), and the small towers (see Palladio’s Tempietto Barbaro). And yet the whole looks perfectly Wagnerian in its polished tightness and beautiful proportions.

The inside, which can be visited on Saturday mornings, was made for psychiatric patients – no sharp edges, careful decorations, spacious confessionals, emergency exits. The stained glass windows are among the most beautiful works of Koloman Moser (1868-1918), a founder of the Wiener Werkstätte workshop. Location.

#48 - Post Office Savings Bank (1904-1906)

After 1898, Otto Wagner moved away from the cheerful plant motifs of the international Art Nouveau toward a more austere and geometrical architecture. Instead of pink floral ornaments (see Majolica House above), the facade of the Post Office Savings Banks consists of plain white marble slabs “anchored” to the walls by simple aluminum rivets. Wagner's focus shifted to structural rather than decorative considerations: it's one of the first buildings in Vienna using reinforced concrete and aluminum details.

The impressive hall inside is lit by sky windows and the floor is made from glass tiles to provide daylight to the sorting room downstairs. The building, which anticipated stripped-down functional modern architecture, is currently home to the University of Applied Arts and there's a cafe on the ground floor open to the public. Location.

#49 - Neustiftgasse 40 (1909-1912)

Otto Wagner's last residential work shows how far he moved from the historicism of his early years in the 1880s (see Stadiongasse 6-8 above). Few traces of the classical vocabulary remained; the building is functionally expressive with simple curtain walls and uniform-sized windows and floor heights. And yet, Wagner didn't feel the need to drop all ornaments as the Bauhaus architects so fiercely insisted on a decade later: bands of gentle glazed tiles accent the lower floors, evoking the rustications of Renaissance buildings. The outsize cornice, a Wagner signature, is also still there. The coolest feature? The address emblazoned with giant letters on an exterior panel facing Döblergasse. Location.

#50 - Zacherl House (1903-1905)

An early masterpiece by the Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik (1872-1957), one of the most talented pupils of Otto Wagner. Plečnik dressed the reinforced concrete frame in vertically accented polished granite slabs, while 28 muscular figures of Atlas hold up the cantilevered cornice. On the facade, a statue of Archangel Michael defeats a creature, a hat-tip to the Zacherl family’s insecticide business.

The building represents a transition between late-period Viennese Art Nouveau and the decor-free modern of Adolf Loos. (Plečnik, who is regarded as a national hero in Slovenia, moved away from this style of architecture with his later works in Ljubljana.) Location.

#51 - Purkersdorf Sanatorium (1904-1906)

Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956) is best known as the co-founder of the Art Nouveau furniture workshop, the Wiener Werkstätte, but he was also a prolific architect. His most notable work – besides the Stoclet Palace in Brussels – is the upscale sanatorium in Purkersdorf, a quaint Viennese suburb reachable within twenty minutes from Westbahnhof (#S50 train).

The outside is classical-looking with a centrally projecting block, but almost completely decor-free, with only a black-and-white checkered pattern framing the windows. In line with Hoffmann’s idea of “Gesamtkunstwerk,” he and his colleagues designed all of the interior details too, some of which have since become celebrated design pieces, including Koloman Moser’s Purkersdorf Armchair. Today, the building is part of a public nursing home, but visitors can walk around the premises and catch glimpses of the inside, still furnished with Wiener Werkstätte objects. Location.

#52 - American/Kärntner/Loos Bar (1907)

Architect Adolf Loos (1870-1933) famously railed against the use of ornaments – his polemic is titled “Ornament and Crime” – but he liked using rich, expensive materials on his buildings and interiors. This tiny cocktail bar off Kärntner Strasse is a study in Loos’s less is more approach: coffered marble ceiling, mahogany wall panels, and the backlit alabaster lend the dark and atmospheric space a festive vibe without superfluous decorative elements.

The place gets crowded in the evenings, but during the day they will allow you to linger over a drink and take in the details. A copy of the portrait of the notorious coffeehouse poet and Loos-friend, Peter Altenberg (1859-1919), still hangs on the wall. Location.

#53 - Looshaus (1910-1912)

Today, Adolf Loos is regarded as a key figure of modern architecture, but when his decor-deprived design plans for Leopold Goldman's upscale men’s clothing company, Goldman & Salatsch, were submitted in 1909 to the Viennese authorities, a huge scandal erupted. No elaborate window frames? Simple plaster covering the upper floors of a building located right across the Imperial Palace where Emperor Franz Joseph lived? Travesty! The conflict was finally resolved when Loos proposed the addition of bronze window boxes to the upper floors, in which, according to the land registry, flowers were mandated to be kept. (According to local lore, the Emperor never again used the entrance facing Loos’s building.)

Loos actually did dress up the ground floor: the main entrance with gorgeous Tuscan columns of expensive green Cipollino marble, the side entrance with speckled red Skyros marble. Location.

#54 - Knize store (1910)

Less-known about Adolf Loos (1870-1933) is that he designed many apartment interiors and store portals. One of his loyal clients was Knize, a high-end men's tailoring shop founded in 1858 and still around today. Located on Vienna’s upscale shopping street, the Graben, the store portal features thick polished granite emblazoned with the company's royal credentials. Loos did all of the interior details complete with timber and marble cladding; most famous is the pendant lamp hanging from both fitting rooms. Try glimpsing the upstairs, too. Location.

#55 - Steiner House (1910)

Featured in architecture books around the world, Adolf Loos's Steiner House is considered to be one of the first modern residential buildings. Especially novel are the sides (and the back, but it isn't visible from street level) with massive planar surfaces simply coated in white stucco and punctuated by unadorned sharp-cut windows. The inside showed Loos's so-called Raumplan – interconnected spaces separated only by curtains – sprinkled with cozy alcoves and small elevations. Minutes from here in Vienna's upscale Hietzing neighborhood (District 13) stands also Loos's Scheu House, see below, from a couple of years later. Location.

#56 - Scheu House (1912-1913)

Designed for a well-to-do progressive lawyer and his wife in 1912, the Scheu House is a good example of the residential architecture Adolf Loos (1870-1933) pioneered years before it became the norm: plaster-covered concrete frame, spare facade, terraced and flat roof, free floor plan. All of these features ushered in modern architecture of the 1920s. Lined with classical villas, the Scheu House stands out from its upscale residential neighborhood of Hitzing in District 13 (near the Schönbrunn Palace). The building is privately owned and can only be viewed from the street. Location.

#57 - Haus Wittgenstein (1926-1928)

Together with architect Paul Engelmann, who was a student of Adolf Loos, the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) designed this white cubical townhouse for his sister, Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein. The wealthy Wittgenstein family was a major patron of the Viennese Secession artists and Klimt painted a portrait of Margaret, which currently hangs in Munich’s Neue Pinakothek.

Despite the plain facade, the house feels more classical than similar-looking Bauhaus buildings from this era because of its high ceilings and elaborate windows, doors, and fittings made from expensive materials. Since 1975, the building has belonged to the Bulgarian Cultural Institute and can be visited by appointment (email: [email protected]). Location.

#58 - Karl-Marx-Hof (1927-1930)

With the 1918 collapse of the Habsburg House and Austria-Hungary, the newly formed Austrian Republic was much reduced in size. Vienna drew tens of thousands of people from territories that fell outside the country’s new borders. This created a critical need for new housing, especially for workers, which the city’s Socialist government – during the “Red Vienna” period of 1918-34 – addressed with huge public housing and infrastructure projects.

Most famous is architect Karl Ehn's monumental Karl-Marx-Hof, a socialist utopian city within the city, complete with 1,400 apartments, kindergartens, communal washing rooms, playgrounds, and green spaces. Repeating red towers with flagpoles project proudly from the yellow facade and soar over this otherwise upper-class neighborhood in District 19. By today’s standards, the apartments are small but many come with sizable balconies and the area is lively and well maintained. It takes twenty minutes to reach the Karl-Marx-Hof from the city center with the U4 subway line. Location.

#59 - Villa Beer (1929-1931)

Architect Josef Frank's Villa Beer is a modernist luxury building from interwar Vienna, one that's been compared to Mies van der Rohe's Villa Tugendhat (here too, the initial owner was a well-off and cultured Jewish family). Frank (1885-1967) was famous for his humanistic interiors: he dismissed the purist approach of fellow modernists who furnished every inch of an apartment according to their grand utopian visions. Visitors don't have to wait much longer to glimpse such interior – after years of neglect, the building is currently under renovation and will soon open to the public. Location.

#60 - Vienna Werkbund Estate (1929-1932)

Inspired by the famous 1927 Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart, this model housing exhibition was built in the Viennese suburb of Hietzing in District 13. Consisting of 70 small standalone residential homes designed by leading modern architects such as Josef Frank, Adolf Loos, Josef Hoffmann, Gerrit Rietveld, and Richard Neutra, the purpose of the exhibition was to promote the modern way of life in Austria.

When the exhibition ended in August 1932, the houses were sold to middle and lower-middle-class buyers (unlike the Karl-Marx-Hof, above, these houses weren’t targeted to workers). The City of Vienna, which owns the estate today, has a helpful online tour of the most interesting buildings. By public transport, the Werkbund estate is reachable within thirty minutes from downtown. Location.

#61 - Hochhaus Herrengasse (1931-1932)

Known as Vienna’s first skyscraper, this luxury building occupies the upscale Herrengasse, where a Liechtenstein Palace once stood. Similar to the New York skyscrapers that sprung up around this time (1930s), the Hochhaus has a stepped-back facade, so the 16-story tower is only visible from certain angles at the street level.

A long list of celebrities have lived here over the years, including the actor Christoph Waltz. Unfortunately, the inside, which is occupied by offices and private apartments, can’t be visited, but the marble-clad reception area is open to the public. There, encased in glass, you’ll find two detailed paper models of the building. Also: a fun, glass-walled cafe hides on the ground floor. Location.

#62 - Esterházypark Flak Tower (1943-1944)

During WWII, Nazi-ruled Vienna erected three pairs of enormous air-defense towers to protect the city from Allied bombings. Forced laborers and prisoners of war built these reinforced concrete monsters that were also used as air-raid shelters for the civilian population. The 11-story control tower in Esterházypark has since transformed into a popular aquarium, the House of the Sea, featuring sharks, turtles, and other maritime creatures. The top floor, accessible for free, provides stunning 360-views. Its sister tower is located in nearby Stiftgasse, but that one can't be visited. Location.

#63 - Volksgarten Pavilion (1951)

Fans of mid-century modern architecture and design should pay a visit to Oswald Haerdtl's pavilion right inside the Volksgarten, built as a milk bar during the impoverished years of post-war Austria. The skeletal structure with a butterfly roof and a massive terrace is straight from the mid-century textbook and operating as a café currently. Next door, the former Volksgarten-Tanzcafé is also by Haerdtl (1899-1959) from the 1950s and a nightclub today. Location.

#64 - Ringturm (1953-1955)

Since Austria was on the losing side of WWII and geographically located between the Soviet and the Western-occupied zones, the Allied powers split the country among themselves for a period of ten years before Austria regained its independence in 1955. The city of Vienna too was divided among the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and France.

There, being so close to one another, architecture became a propaganda tool. The glitzy new high rise of the Vienna Insurance Group, the tallest building in the city after the Saint Stephen’s Cathedral, meant to symbolize capitalist success to the grim Soviet side just across the Danube Canal. The building’s ground floor – Architektur im Ringturm – is known for its rotating set of free exhibitions about architecture in Central Europe. Location.

#65 - Wotruba Church (1974-1976)

It takes a bit of a trek to reach this unusually shaped Brutalist church by the Vienna Woods in District 23. The designer, Fritz Wotruba (1907-1975), was a prominent sculptor known for his blocklike, cubic statues, and this building, too, feels like a giant sculpture. The church consists of 152 slabs of rough-hewn concrete arranged like Jenga blocks with glass panels filling the gaps and admitting daylight. The siting is perfect: the church sits atop a small hill surrounded by nature and gradually reveals itself to churchgoers and visitors. Location.

#66 - Vienna International Center & UN Headquarters (1973-1979)

Austria was a neutral country during the Cold War (1947-1991), and the country's famous Chancellor, Bruno Kreisky (1911-1990), lobbied hard to reinforce this status by bringing prominent international organizations to Vienna. In 1979, the United Nation's third headquarters opened in a far-flung location between the Danube River and a onetime branch called Old Danube, an area now known as Vienna International Center.

Six imposing and rather generic Y-shaped office towers anchor the UN institutions. This part of the city, which is also home to a business district and several skyscrapers, can be accessed easily by the U1 subway line. Location.

#67 - Domenig-Haus (1975-1979)

Günther Domenig (1934-2012) was a well-known and protean architect in Austria. His most famous work, the former Z-Bank building on Vienna’s Favoritenstrasse in District 10, blends brutalist, high-tech, and postmodern elements. The exposed concrete skeleton and structural parts are clad in an expressive facade of stainless steel plates that evoke a human face. The lower floors are occupied by a restaurant today and can be visited. Location.

#68 - Hans Hollein designs in the City Center (1960s-2003)

Austria’s foremost postmodern architect, Hans Hollein (1934-2014) won the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s Nobel, in 1985. For his “wit and eclectic gusto that draws upon the traditions of the New World as readily as upon those of the Old,” argued the committee. To unpack what this means, visit the storefronts Hollein designed in Vienna’s city center just steps from one another. They remind me of abstracted shapes of classical forms; always beautifully polished and taut, sometimes playful. The Retti candle store (1965) at #12 Kohlmarkt, shown above, consists of a deeply recessed aluminum cover shaped like an Ionic column.

Find more Hollein-storefronts at #7 Kohlmarkt, and #26 and #31 Graben. Hollein’s more controversial works include the Haas House (1990), a strangely shaped commercial building right across from the St. Stephen’s Cathedral and covered in reflective glass, and the beautifully cantilevered entrance portal of the Albertina Museum (2003). Location.

#69 - Hundertwasser House (1983-1985)

A favorite of tourists, the Hundertwasserhaus is an attention-grabbing block of public housing in Vienna’s District 3. The designer, Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928-2000), belonged to the generation that was disillusioned by modernist architecture and its predictably clean, rational, standardized, sleek shapes (“the straight line is godless,” he said). The Hundertwasser House is none of those things.

This idiosyncratic building with 52 residential apartments consists of irregular shapes, harsh colors, undulating floors, and overblown decorations. Trees are everywhere; they grow on the roof and project from the apartments (Hundertwasser was an early proponent of environmentalism). Architects often criticize the building for being kitsch, but you should be the judge of that. A few blocks away there’s a Hundertwasser Museum inside the Kunst Haus Wien, which was also designed by him. Location.

#70 - Rooftop Remodeling Falkestrasse (1987-1988)

This strange object on the rooftop of a historical building in Vienna’s city center is one for architecture geeks: in 1988, Wolf Prix (b. 1942) of Coop Himmelblau designed what was among the first completed works of the deconstructivist style. This type of architecture became popular with the buildings of Peter Eisenman and Frank Gehry and is known for its strangely angular shapes, as if built from fragments and made to be intentionally uncomfortable. Prix’s steel-and-glass rooftop extension was made for the offices of a local law firm. Unfortunately, not much of it can be seen from the street level, but at least you know it’s up there. More photos. Location.

#71 - Collegium Hungaricum (1996-1998)

László Rajk was a leading postmodern architect in Hungary, best known for designing the wild and weird Lehet Market in Budapest. His building for the Hungarian Institute of Culture, located in Vienna’s Leopoldstadt (District 2), is another eccentric and playful work. Rajk was primarily a set designer and the building looks as if it belongs to the theater stage: The squashed windows, the impossibly curving facade, the bright red, and those strange metal objects are embellished and theatrical. Location.

#72 - Museums Quarter (1998-2001)

Vienna’s Museums Quarter is an exemplary case of giving new meaning to a historical building complex that has lost its original purpose. In 2001, the Baroque-style imperial horse stable from the early 18th century was transformed into a cultural hub with two newly erected museums, one for the Leopold, the other for the mumok. In addition to these anchor institutions, the area also features cafes, a bookstore, a children’s museum, an architecture center, and artists’ residencies. It’s also a popular hangout of local residents. Location.

#73 - Gasometers (1999-2001)

Even the international press joined the fanfare when four abandoned 19th-century gas storage facilities on the outskirts of Vienna found a new purpose in 2001. The star architects behind the project, including Jean Nouvel and Wolf D. Prix from Coop Himmelb(l)au, retained the brick exteriors but filled the insides with apartment buildings, retail stores, and performance halls. Twenty years hence, in the current day, it’s a depressing experience to roam these cylindrical buildings: cheap commercial units, half-empty offices, and decaying residences stare back at visitors. Evidently, something went wrong along the way. Location.

#74 - Sofitel Vienna (2010)

A work by a Pritzker-winning architect always merits attention, but Jean Nouvel’s glass-walled skyscraper in Vienna looks more generic than some of the French master’s other buildings. Located in Leopoldstadt (District 2), right on the bank of the Danube Canal, the structure is home to the 182-room, five-star Sofitel (SO/ Vienna). The most striking feature of the hotel is the panoramic 360-degree views from Das Loft, the restaurant and bar perched on its top floor. Location.

#75 - Library and Learning Center – Vienna University of Economics (2008-2013)

The new campus of the Vienna University of Economics and Business, located in District 2 next to the Prater park, was commissioned from six prominent international architecture firms. At the heart of it stands Zaha Hadid’s Library and Learning Center. Fans will quickly recognize her effortlessly fluid, crowd-pleasing shapes, especially that of the tilted black concrete box that cantilevers over the public plaza and contains the library.

The inside – sleek and white and curvilinear – brings to mind Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim and a luxury cruise ship. Hadid (1950-2016) was no stranger to Vienna: for years, she taught an architecture masterclass at the University of Applied Arts. Location.

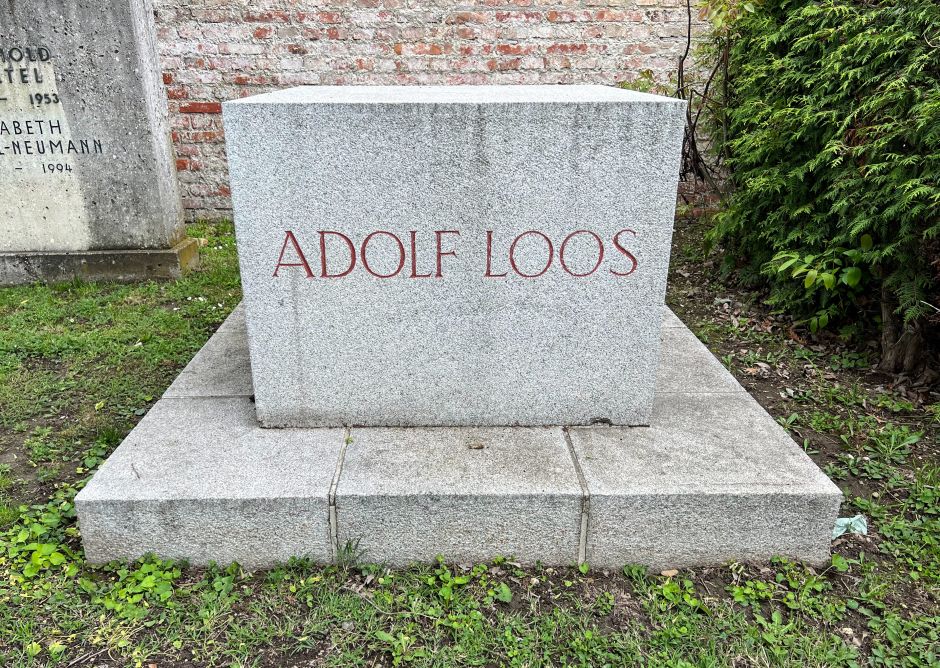

#76 - Graves of Viennese architects

If you also like to roam through the graves of famous architects, head to Vienna's central cemetery. It's fascinating to observe the tombstone decorations, usually reflecting the style of the deceased: Gothic inscriptions for Friedrich von Schmidt (who did the medieval-looking City Hall), Greek elements for Theophil Hansen (Austrian Parliament), a minimal stone for Adolf Loos (Looshaus), which he designed himself. Most architect-graves are located in the cemetery's section 14, within minutes of the main entrance at Tor #2 (except Loos, who is to the left, all the way at the end: Group 0, Row 1, #105.) Location.