Sadly, I’m no aristocrat and this isn’t the 18th century, but I did go to Italy in search of art and architecture. Part 4: Milan, Turin, and Mantua.

I've been covering art and architecture recently, so an immersive visit to Italy seemed like a good idea. I wanted to see for myself the palaces, the churches, the frescoes, the paintings (or whatever remained of them) which had such an influence on Western art. This concept is nothing new, of course. The idea of a Grand Tour goes back at least to the 17th century when it was standard practice among the more enlightened members of the high nobility to spend a few years traveling through Italy to study – or pretend to – the classical world through its ruins.

Unfortunately I don’t sit on a dynastic fortune, so my Grand Tour was compressed into an intensive three-months period which took me from Venice to Rome, with a dozen cities and more than a hundred museums in between. What follows isn’t a collection of amusing travel stories – sorry! – but my attempt at making sense of the artworks I've seen. I included specific recommendations for museums and architecture with a map in case you're inspired, and also a short food and wine summary of the regions I visited. Part 4: Milan, Turin, and Mantua.

Milan in a Nutshell

The richest city in Italy, Milan feels a world away from the southern parts of the country in all of its elegant prosperity and capitalist success. Geographically and historically, Lombardy has been close to Germany (ruled by the Habsburgs – first the Spanish side, then the Austrian –for many centuries), so German culture shows itself in many ways, for example, in Milan’s architecture, cuisine, and economy. Never in my life have I seen so many stylish people as in Milan. Not even New York can compare. (Perhaps a function of fashion week overlapping with my visit?)

The Food and Drinks of Lombardy

Unlike in the parched southern soils of Italy, cows find a rich pastorage up here, meaning that Lombardy's choice of fat is butter, not olive oil, with a solid lineup of cheeses. Best of all is the blue Gorgonzola – Gorgonzola is a little town north-east of Milan – followed by the creamy Mascarpone and the neutral Stracchino.

The valley of the Po River in the Lombardy plain is home to Europe's rice-growing since the 15th century, making risotto alla milanese the essential dish of the region. Simple and delicious: rice cooked in butter and consommé and flavored with saffron (and eaten with a spoon). Corn is also an important grain, so cornmeal mush (polenta) appears as a side on many plates.

Like it or not, the Wiener schnitzel originates from the Cotoletta alla milanese; the Milanese prefer bone-in veal chops to Vienna’s filet, arguing it offers a better proportion of fat and meat. But the German influence goes both ways: Lombards eat their meats braised and stewed, as with the ossobucco (braised veal shanks), and flavored with parsley, sage, rosemary, onion, and celery. The Italian Christmas sweet bread, Panettone, is basically the same as what's known as the Gugelhupft across Central Europe.

My sister, who joined for the trip, reminded me that Milan is the home turf of the Campari. One of the company's first bars, Camparino, is still within the famous Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II; very touristy and very fun – I left with a renewed passion for the Campari spritz. Unlike with the hilly Piedmont, the wines of flat Lombardy aren’t especially remarkable, which explains why a fortified and flavored wine (Campari) and an herb-infused amaro (Fernet-Branca) are the two central drinks of this region.

Napoleon’s Brera

Napoleon made Milan the capital of his short-lived Italian Kingdom in 1797 and he wanted to transform the Brera into the Louvre of Italy. His troops went about confiscating masterpieces near and far and today, together with Florence’s Uffizi and Venice’s Gallerie dell'Accademia, the Pinacoteca di Brera is the grandest old masters collection in Italy.

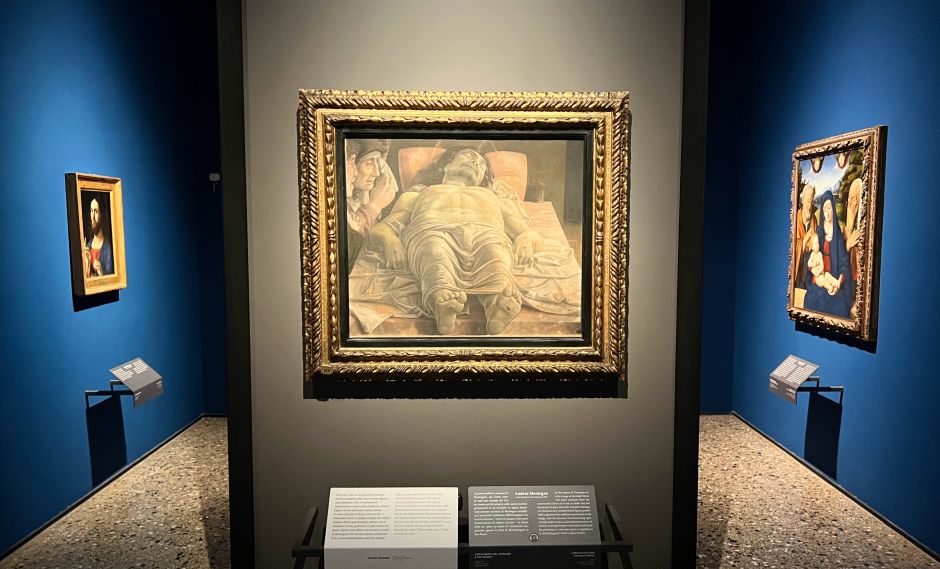

There are many peerless works across the 36 halls, so I’ll just mention the few I admired most, starting with Andrea Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1480). There’s the spectacular foreshortening of the body, that spatial brilliance Mantegna came to be known for. But this painting has a human side, which isn't typical of Mantegna – the weeping figure of the Virgin Mary on the left, hardly noticeable at first, and all the more powerful for it.

The Finding of the Body of Saint Mark (1562-1566) shows Jacopo Tintoretto at his best. Along with Titian and Paolo Veronese, Tintoretto was the star painter of golden-era Venice in the 1550s, known for an idiosyncratic style that this painting perfectly captures: deep diagonal perspectives, high-energy figures glowing in the dark, drama and confusion everywhere. We see Saint Mark, the patron saint of the Venetian Republic, appearing resurrected next to his own body, curing the sick and the demon-possessed, while gesturing to the men to stop the desecration of the tombs because he has been found. Wild stuff.

The third is an almost bacchanalian Last Supper (1585) by Paolo Veronese, who, irrespective of the job given, was always most interested in depicting the lavish life of the Venetian aristocracy. He relegates Jesus to the side of the canvas and instead directs our eyes to this unruly dinner party featuring dwarf performers, fine clothes, and lots of wine. Good fun is what Veronese liked. In addition, the Brera has singular works by Piero della Francesca, Giovanni Bellini, Carlo Crivelli, Caravaggio, Pietro Longhi, Gianbattista Tiepolo, Francesco Hayez and many others.

Biblioteca Ambrosiana & Poldi Pezzoli Museum

There are two important museums near the Brera. The Ambrosian Library, founded in 1609 by the Archbishop of Milan, is known for its manuscript collection and for Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus – twelve leather-bound books filled with his reversed shorthand writings and drawings of contraptions that occupied his roving mind. The Archbishop, Federico Borromeo (cousin of the canonized counter-reformationist archbishop, Carlo Borromeo), also owned Raphael’s full-sized preparatory work for the School of Athens (1509), as well as paintings by Leonardo, Caravaggio, Sandro Botticelli, and Titian among others.

Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli was a 19th-century Italian nobleman and art collector. His treasures are still exhibited in the downtown palazzo-museum where Mr. Poldi Pezzoli lived and which was nearly empty on both of my visits. A late-period Botticelli, a Giorgione portrait, and Piero della Francesca’s Saint Thomas of Tolentino have stuck in my head. Plus, for reasons of patriotism, a Raphael-pupil’s depiction of Elizabeth of Hungary. The 13th-century Saint is shown with her apron full of roses (she managed to avoid her husband’s wrath when the bread she secretly took to the poor miraculously transformed into roses).

Leonardo in Milan

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), originally from Florence, moved to Milan in 1482 upon the invitation of the renaissance Duke Ludovico Sforza and spent more than twenty years there in two phases. Milan lacked the thriving artistic milieu of contemporary Florence and some experts think the move did no good to the painterly development of even such a genius as he.

His presence in Milan completely upended the Lombardian school of painting, whose pivotal figure had been the early-Renaissance master Vincenzo Foppa (1430-1515). The Brera, the Ambrosiana, the Poldi Pezzoli, and the Sforza Castle’s painting gallery all have sections dedicated to the local artists and it’s instructive to observe the extent to which Leonardo’s followers – Marco d’Oggiono, Bernardino Luini, Andrea Solario, Antonio Boltraffio, Giampietrino – fell under his sway.

Many art historians have criticized this slavish imitation and, indeed, lots of these paintings seem like caricaturistic copies of Leonardo’s works: one-dimensional, and lacking in Leonado's subtlety and complexity.

Michelangelo's Pietàs

Michelangelo made three sculpture groups of the Virgin Mary with the dead Christ. The sequence of these works show his stylistic evolution over the course of his long life. His first and best-known Pietà, in the Saint Peter’s Basilica, is the most technically brilliant and lifelike of the three (astonishing details in Mary’s robe and in the completely collapsed body in her lap). The work of a 23-year-old genius looking to prove himself.

The other two are both from late in life and more unconventional. Overtaken by grief, the figure of Nicodemus is especially memorable in the Bandini Pietà (1547-1555), now in Florence’s Museo dell ‘Opera del Duomo. His tender affection toward Christ is a reflection of Michelangelo's own religious feelings and many believe that Nicodemus actually represents Michelangelo himself.

Milan’s Sforza Castle holds Michelangelo’s last Pietà, which was also his last sculpture. He made it for his own tomb and worked on it until he died in 1564 at age eighty-eight. It’s an unusually expressive (and unfinished) work, two elongated, thread-like figures floating in space and nearly fused into a single body. I drift between finding it extremely moving and too unfinished in its current state. Why in Milan? The city bought the sculpture in 1952 from the owners of the Palazzo Rondanini in Rome, where it was held for centuries.

Milan’s Sistine Chapel & Donato Bramante

I’ve heard locals refer to the frescoes in the Saint Maurice al Monastero Maggiore church as “Milan’s Sistine Chapel.” That is probably too tall a comparison, but Bernardino Luini (1480-1532), Leonardo’s most gifted pupil, and his followers cloaked the inside with an amazing fresco cycle (1520s). Both the dividing wall that separates the nun’s section from the rest of the nave and the side chapels; in the Besozzi Chapel, Luini painted scenes from the life of the notably elegant Saint Catherine of Alexandria, including her gruesome killing, first, unsuccessfully, by a spiked wheel, then, finally, by decapitation.

The church is on the way to Leonardo’s Last Supper at the Santa Maria delle Grazie. Be sure to book in advance otherwise you’ll end up like me – tickets sold out months in advance – and have to console yourself with the church’s dome and apse. Those massive circles, squares, and barrel vaults came from Donato Bramante (1444-1514), who established Renaissance architecture in Milan. (Later he was chief architect at the Vatican for Pope Julius II and drafted the initial plans for the new Saint Peter’s Basilica).

The Duomo & The Museo del Novecento

Even by Italian church-standards, the Milan Duomo is huge (the biggest in Italy, since the Saint Peter’s is officially in the Vatican). I love peering at its facade because it’s rare to see such an unashamed mixing of (neo-)Gothic and Baroque details on a building. It’s a spectacular sight but not a pretty one – the vertically racing slender Gothic spires and tracery are in open competition with the triangular and curved window pediments which seem completely out of place.

The best views of the Duomo are actually from the adjacent Museo del Novecento, a smooth neoclassical building of Mussolini-era Italy. This recently opened (2010) museum focuses on the most well-known art movement of 20th century Italy – the machine-obsessed Futurists, paintings by Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Carlo Carrà (I hadn't appreciated the close visual connection between Futurism and Cubism). Those more into Giorgio de Chirico’s wistful surrealism, Giorgio Morandi’s delicate still lifes, or Lucio Fontana’s slit canvases will also have plenty to enjoy here on three expansive floors.

Villa Necchi

I’m glad my sister convinced me to stop by the Villa Necchi, located in a fancy residential neighborhood near the center. This vast, luxurious modernist house belonged to the Necchi Campiglio family, industrialists who got rich from manufacturing sewing machines. The building is what happens when money and good taste come together (designed in 1932-35 by Piero Portaluppi). While evidently modernist, the house is less radically avant-garde than its Bauhaus-inspired contemporaries, such as the Villa Tugendhat in Brno, which is another way of saying that it’s not a programmatic building but a home made for living in.

Turin

In 1559, the Dutchy of Savoy moved its base from Chambéry to nearby Turin and came to play an important role in the development of the region (Piedmont) and Italy as a whole.

The picture gallery of the Royal Palace (Sabauda) is unexpectedly ambitious, not far behind the great museums of Italy. The core had been amassed by the Savoys, but General Eugene Savoy's wonderful private collection from Vienna also ended up here (Prince Eugene came from a cadet branch of the Savoy family but never lived in Turin). I saw very good works by Paolo Veronese, Guido Reni, Francesco Albani, Anthony van Dyck, Peter Paul Rubens, Sebastiano Ricci, and Francesco Solimena; these last two were tasked by court architect Filippo Juvarra (1678-1736) to decorate the royal apartments.

The word risorgimento refers to the sequence of events that led to the unification of Italy and the creation of the modern country in 1861. Through military force and political cunning, the various parts of the peninsula – that included an antagonistic pope and the Habsburg-run northern states – gradually submitted to the centralized rule of the House of Savoy and the not especially skilled first king of Italy, Victor Emmanuel II (1820-1878). Hence Turin the first capital of Italy, and hence Turin the home to the most important of the many risorgimento museums.

The exhibition takes place in the striking Baroque Palazzo Carignano. Still, I'm not one for military museums. After about the second hall, battle-scene paintings, portraits of generals, and military flags start to melt into a haze of nothingness. It didn't help that the English-language wall texts were minimal.

What Borromini was to Rome was Guarino Guarini (1624-1683) to Piedmont. Guarini actually tripled as an architect, a priest, and a mathematician. He became known for his strange and unexpected domes, mainly that of the San Lorenzo church and the Chapel of the Holy Shroud, both located right by the Royal Palace.

As with Borromini, he piled mismatched elements atop one another, disregarded the rules of proportion – the chapel has an unbelievably stretched drum – and somehow made it all work. The chapel's black marble ground level from which springs the maze of gray hexagonal segmental ribs is an unforgettable view.

Filippo Juvarra's hilltop church, the Basilica di Superga, will have to wait until next time. As does the Pinacoteca Agnelli, the private art museum of the family that founded Fiat, which is based in Turin.

Leon Battista Alberti and Giulio Romano in Mantua

Located near Milan, Mantua is a small but very special city, not to be missed. The Gonzaga family set up a model duchy here in the 15th and 16th centuries with approval but little oversight from the Holy Roman emperors. Like other important Renaissance centers, such as Florence, Urbino, and Ferrara, Mantua drew epoch-making artists and architects, including Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), who designed two singular churches for the city.

The Sant'Andrea is a textbook example of Alberti’s brand of early-Renaissance (although not yet finished at his death in 1472): a muscular triumphal arch entrance leads to an amalgam of amazing barrel vaults with coffered ceilings and a spectacular dome. Alberti’s inspiration for these great masses came directly from the triumphal arches and thermal baths of ancient Rome, which he studied with exemplary zeal in the 1450s, sharing an enthusiasm with the cultured Pope, Nicholas V.

The effect of the Sant'Andrea had to be especially striking in 15th-century Italy, used to Gothic arched windows, ribbed vaults, and compound piers.

Mantegna and Rubens at the Gonzaga Ducal Palace

The Gonzaga Ducal Palace in the city center is more impressive – and much bigger – than its indistinct medieval shell would imply. The endless halls, although much depleted by now, show off the Gonzaga wealth complete with an ancient sculpture collection, a Wunderkammer (narwhal tusk? of course!), and works by the young Peter Paul Rubens. The Flemish master was the Gonzaga court painter between 1600 and 1609.

Most famous, though, is the Camera degli Sposi, a semi-private reception room covered in the frescoes of Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506). The greatest early-Renaissance painter in all of Italy, Mantegna spent much of his life in the employ of the Gonzagas. The brilliant scenes – made in 1465-1474 – convey, predictably, the dignity, importance, and benevolence of Ludovico Gonzaga, Mantua’s ruler. The fresco cycle is crowned by a Baroque-style illusionistic ceiling painting, one of the first ever.

Andrea Mantegna’s House

In the 1470s, Mantegna designed his own house in Mantua (a museum today with free entry). It’s a love letter to his beloved ancient Rome whose forms he so much liked to depict on canvas – using only circles and squares, the house’s layout consists of a cube at the center of which is a cylindrical courtyard. It’s perfectly fitting that Alberti’s other Mantua church, the San Sebastiano (1460s), with its Greek cross plan inscribed in a square, stands across from the Mantegna house.

Giulio Romano & Palazzo Té

“In Mantova, go to the Palazzo Té before doing anything else,” advised my friend. Palazzo Té (1525-1535) is the Gonzaga summer estate on the outskirts of the city, a fifteen minute walk from the center. What makes the palazzo such a cult destination isn’t so much its size or opulence, but the way its architect, Giulio Romano (1499-1546), subverted the established forms of classical and renaissance architecture and designed a playful, caricaturistic, “mannerist” building.

Born in Rome, Giulio Romano was a painter and the most talented pupil of Raphael. He painted many of the famous scenes in the Papal apartments, for example the Fire in the Borgo (1514-1517), and finished Raphael’s works after his untimely death. Romano’s muscular figures in frantic motion betray the influence of Michelangelo, whose Sistine frescoes were located just steps away from the Papal apartments. With time, Romano’s painting style became, basically, a caricature of Michelangelo, as his architecture became a caricature of the Renaissance forms.

In 1524, the Gonzagas hired Romano to work as court architect in Mantua, which he did until his death two decades later. Romano wasn’t obsessed with Roman forms like Alberti and Mantegna, nor was he interested in evolving the renaissance vocabulary like Bramante and Michelangelo. What he did was ridicule it.

The window pediments of the Palazzo Té, for example, are broken at the top, the triglyphs are about to slip off from their place, the walls are over or under-rusticated. Things appear too big or too small. It’s a very strange place.

And the inside! The vertigo-inducing Hall of Giants, frescoed from top to bottom with distorted figures in agonizing pain, crushed by the angry Olympus gods. Romano makes Rosso Fiorentino and Tintoretto seem like mere beginners. The Hall of Cupid and Psyche amounts to Baroque illusionist drama before the Baroque. He must have had a lot of fun.

I’m surprised Giulio Romano isn’t a “bigger name” today. Perhaps because influential art critics, such as Bernard Berenson, dismissed him as a non-entity or viewed his art as self-serving. I don't think that's fair. For example, Romano's last work, the design for the Palazzo Thiene (1540s) in Vicenza, Palladio’s city, is totally magnificent in its scale and decorative elements. Of course, not without a few idiosyncracies – fingerprints of a subversive architect-genius.