Sadly, I’m no aristocrat and this isn’t the 18th century, but I did go to Italy in search of art and architecture. Part 3: Bologna, Ferrara, Ravenna, Rimini, and Urbino.

I've been covering art and architecture recently, so an immersive visit to Italy seemed like a good idea. I wanted to see for myself the palaces, the churches, the frescoes, the paintings (or whatever remained of them) which had such an influence on Western art. This concept is nothing new, of course. The idea of a Grand Tour goes back at least to the 17th century when it was standard practice among the more enlightened members of the high nobility to spend a few years traveling through Italy to study – or pretend to – the classical world through its ruins.

Unfortunately I don’t sit on a dynastic fortune, so my Grand Tour was compressed into an intensive three-months period which took me from Venice to Rome, with a dozen cities and more than a hundred museums in between. What follows isn’t a collection of amusing travel stories – sorry! – but my attempt at making sense of the artworks I've seen. I included specific recommendations for museums and architecture with a map in case you're inspired, and also a short food and wine summary of the regions I visited. Part 3: Bologna, Ferrara, Ravenna, Rimini, and Urbino.

Bologna in a Nutshell

Italy’s food capital with an unusually strong painting tradition, Bologna offers at least two convincing reasons to visit it. This red-brick capital of Emilia-Romagna with its endless arcaded streets and Europe’s oldest university is usually packed with tourists.

The Food of Emilia-Romagna

Emilia-Romagna is the leading wheat and pasta producer in Italy thanks to a rich soil and the proximity of the Po River. The tagliatelle, the tortellini, and the lasagna are the three pasta dishes of Bologna; the ribbon-shaped, golden-colored tagliatelle is often served with ragu.

The Apennine Mountains on Emilia-Romagna’s southern border have plenty of pigs and cows, meaning that the region is also ham and cheese country. Bologna’s special cooked sausage is the mortadella (in the U.S. they refer to it as “Boloney”). Nearby Parma has its famous ham, in an area with ideal mountain-air for curing. The hams are treated with only a small amount of salt to retain their sweetness. The most prized cut is the culatello, with an especially sweet flavor (very pricey – special occasions only).

Parmesan, the famous hard cheese, is produced in both Parma and Reggio, hence the official name of Parmigiano Reggiano. Modena, next to Bologna, is famous for its balsamic vinegar, an aged, sweet-tart fine wine vinegar. Sommeliers tend to look down their noses at the Lambrusco, Emilia-Romagna’s sparkly, easy-drinking red wine, but, shamefully, I’m a big fan.

Bologna’s Pinacoteca

Bologna’s main picture gallery, the Pinacoteca Nazionale, was a wonderful discovery. It’s one of those regional museums in Italy that doesn’t just shed light on the local painters but also shows how they were influenced by Florence, the art capital of the 15th century. For example, the intense colors, languid figures, and studied composition of the Bologna-based Francesco Francia (1444-1517) brought to mind his exact contemporary, Pietro Perugino, one of the best painters of Italy at the time.

Other highlights of the museum include an amazing polyptych (1330-1335) by Giotto. It’s one of the few works he actually signed, not that it was needed: the saints and the two angels have that unmistakable – and totally addictive – Giotto-esque look, slightly creepy, complete with almond eyes and bronze faces.

Also at the Pinacoteca: a late-period Crucifixion by Titian (Jesus and the Good Thief, 1563), and what has to be Parmigianino’s cutest painting (Madonna with Child and Saints Margaret, Hyeronymus and Petronius, 1529). I discovered a Bologna painter who has since become a favorite: Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665-1744). Far from the tiresome Baroque grand manner of the early 18th century, Crespi’s fluid figures have an undeniable human touch.

The Carracci School

Just as Bologna started to enjoy the glories of a humanist city-state under the Bentivoglio family, it was annexed in 1509 by the Papal States of the bellicose Pope Julius II. From then on, Bologna was relegated to a permanent number-two status behind Rome. Still, the city was home to a very important art school at the end of the 16th century helmed by the Carracci family (Ludovico and his cousins, Annibale and Agostino). The Carraccis cut ties with the excessive artifice of the Mannerist style, think Parmigianino, and advocated for paintings that were easily understood by simple and illiterate people, in line with the doctrines of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) and the Counter-Reformation.

The Carracci School – also known as the Bologna School and Emilian Classicism – has been described as a blend of classicism (Raphael's figures and composition) and naturalism (Michelangelo's dynamism and figures). Given Bologna’s close links to Rome, the most successful Carracci-pupils ended up working on important commissions for the high clergy. Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), for example, frescoed the Palazzo Farnese, now the French embassy, and Domenichino (1581-1641) did many of the original altarpieces for the Saint Peter’s Basilica.

In Bologna, the Pinacoteca has a big hall filled with Carracci works while the Palazzo Fava contains famous fresco cycles by the three Carraccis. They show scenes from the life of Jason, the leader of the Argonauts in search of the golden fleece, and from Aeneas's journey to Italy.

Guido Reni (1575-1642), also from the Carracci cradle, became one of the most recognized names in art history, ranked alongside Michelangelo and Raphael. The Bologna Pinacoteca has an entire hall packed with Reni’s cool and silvery representations of saints and Biblical heroes, allowing visitors to judge whether Reni’s expulsion from Mount Olympus by 19th century art critics was justified or not (they thought he was superficial and formulaic). My view: Reni is amazing.

Another heavyweight from Bologna of the early-Baroque period was Guercino (1591-1666). I had been familiar with Guercino’s brand of naturalism and use of light and shadow because of a memorably moving prodigal son painting at the Kunsthistorisches in Vienna. More than anyone else, he was a forefather of the grand Baroque manner practiced in Rome throughout the 17th-century and early 18th centuries.

Only in Italy

I’d walk into a Bologna church, randomly picked, and usually a Guercino, a Guido Reni, or a Carracci painting would be staring back at me from the walls. Often I'd be completely alone and undisturbed. Outside of Italy, these masters are cherished museum-pieces. There's a similar situation in the Veneto with Bellinis, Tintorettos, Tiepolos.

The Gentle Art of Giorgo Morandi

Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) became Italy’s most famous painter of the 20th century despite himself. Morandi wasn’t interested in fame or commercial success, having spent his entire life in Bologna, living in a first-floor apartment with his three sisters and painting almost only still lifes: vases, bottles, and drinking glasses arranged in various combinations. But his simplicity is deceptive. These mundane objects rendered in milky pastel colors have a powerful sense of melancholy and layers of sensibility.

The biggest collection of Morandi paintings is in the Morandi Museum, inside Bologna’s Museum of Modern Art (Mambo). There’s also the Morandi Memorial House near the city center, thanks to one of the sisters who preserved Morandi’s small studio. Evidently, this was a life dedicated to work – his studio doubled as his bedroom. It was both logical and surreal to see the same vases and bottles lying around that feature in his paintings. What crowned my visit was noticing the Giuseppe Maria Crespi pictures hanging on the walls. (Note that the memorial house is open only during the weekend.)

San Petronio, Santo Stefano, San Domenico…

Bologna’s biggest church, the unfinished Basilica San Petronio on Piazza Maggiore, is where Habsburg Charles V had himself crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 1530 by Pope Clement VII. Charles’s troops had sacked Rome a few years earlier so he deemed Bologna a more conciliatory location for this ceremonious event with the Medici pope. Nearby, the triangular Piazza Santo Stefano is the most charming square of Bologna and its namesake Basilica hides a labyrinthine system of exceptionally well-preserved early medieval churches and courtyards.

I didn't know that the Dominican order held its first chapter in Bologna (1220) and that the Dominican order’s founder, the Spanish native Dominic Guzman (1170-1221), is buried in the Basilica of San Domenico. His namesake chapel is anchored by an incredible 13th century marble tomb decorated with carved scenes from Dominic’s life, also featuring three small statues by the young Michelangelo from the 1490s. Above his tomb, a fresco shows Dominic’s ascent to heaven by the hand of Guido Reni.

An Old University

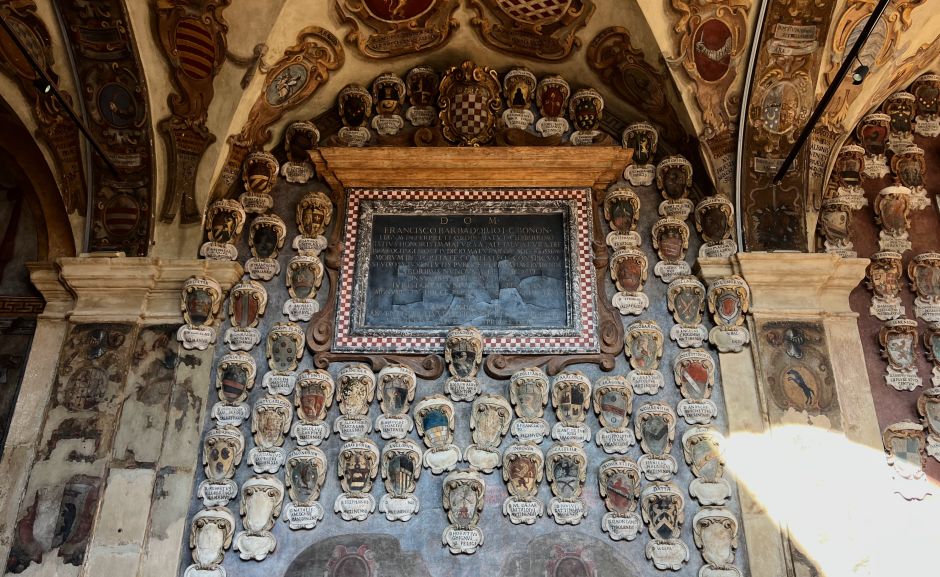

Near the Piazza Maggiore lies the Archiginnasio Palace, the first permanent home of the University of Bologna, Europe’s oldest (1088). Today a public library, classes took place here between the 16th and the 19th centuries.

For a small admission fee, visitors can view the anatomy theater, which is truly a theater: while the professor dissected a human body on a central podium, enraptured students sat around him on elegant tiered wooden benches. Even more striking are the thousands of coats-of-arms that blanket the hallways. They show the name and the place of origin of the university’s most esteemed graduates – an adorable tradition due for a revival!

The Este Court in Ferrara

Apart from Florence and the Medici, the fate of no other Italian city has been so closely tied to its rulers than Ferrara’s to the Este family. Name a place in town and surely there’s an Este connection, starting with the imposing castle in the center, still ringed by a water-filled moat and lined with battlements (those same crenellations recur in Giorgio de Chirico’s famous painting, The Disquieting Muses).

Borso, Ercole, and Alfonso d’Este created a golden period in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. They supported poets, commissioned codices, ordered family portraits, and built plenty of palazzos. The Palazzo Schifanoia, a summer estate within walking distance, still has an extraordinary cycle of early-Renaissance frescoes – the Hall of the Months; 1469 – executed by court painters Ercole de' Roberti and Francesco del Cossa. The cafe in the palace garden is an amazingly restful place.

Cosmè Tura and the Diamanti Palace

I’m partial to another Este court painter, the idiosyncratic Cosmè Tura (1430-1495). I’ve enjoyed in Vienna's KHM his strangely nervous and rugged paintings. There are more of them at Ferrara’s National Painting Gallery inside the Diamanti Palace.

The building, Este of course, is a pilgrimage site for architects and named after the diamond-shaped marble blocks that project from its facade (built in 1493-1503). The same Biagio Rosetti designed it who turned this barren neighborhood into a model of renaissance urban planning at the urging of Duke Ercole Este. The palazzo-lined avenues are very different from the cramped old-old town of Ferrara with its pebble-paved narrow streets.

As with Bologna, Ferrara’s golden period was cut short in 1590 when the Papal States annexed Ferrara and placed it on the backburner. No need to feel too bad for the Este Court, which packed up and moved to Modena and Reggio, cities they continued to rule.

Ippolito d'Este’s Adventure in Hungary

Fun little trivia: Ippolito d'Este, younger brother of Alfonso I, moved from Ferrara to Hungary in 1487 to become the country’s Archbishop (Ippolito’s aunt, Beatrice of Naples, was Queen of Hungary). His lavish life in Esztergom – and in several summer houses across the countryisde – didn’t earn him many favors with the locals and after the death of his patron, King Matthias Corvinus, he thought it better to return to Italy.

Cappellacci con Zucca

Ferrara is still the heart of Emilia-Romagna, so its food isn’t much different from that of Bologna. The famous local dish is the cappellacci con zucca. A hat shaped pasta filled with pumpkin, parmesan and nutmeg and drenched in butter or ragù sauce.

Ravenna’s Mosaics

The scent of salty breeze filled the air from the moment I stepped off the train in Ravenna. Located near the Adriatic Sea and just an hour from Bologna by train, Ravenna is one of the countless cities in Italy with a hundred thousand or so residents; a sleepy provincial town except for the fact that between the 5th and the 8th centuries AD, it was the capital of the Western Roman Empire and later to the Byzantine Empire’s Italian territories. (I often complain that Budapest lives off its Austro-Hungarian past, that it doesn’t have much to show for the present day; well, Ravenna capitalizes on a glorious period that took place 1,400 years ago.)

It’s a complete miracle that so many buildings have survived nearly intact. Decked out in spectacular glass mosaics, these early-Christian mausoleums, churches, and baptistries capture the moment when antique art and architecture transformed from their idealized forms into something coarser, clumsier, but perhaps more expressive.

Abraham and Isaac at the San Vitale

The main landmark is the 6th century San Vitale Church, from the time of Emperor Justinian (482-565), who tried to retake the Western Roman Empire from the German tribes. The typically Byzantine church has a central octagonal shape ringed by apses, one of which contains the jaw-dropping mosaics. It shows the Emperor, looking dapper in earrings and a purple dotted robe, flanked by church and lay leaders (his wife, Theodora, is on the opposing wall with her retinue).

Of the Biblical themes, there’s an unforgettable depiction of the Sacrifice of Isaac: Abraham tenderly holds the head of the vigorous child, who’s starting to suspect what’s coming when at the last second an angel’s hand appears to stop Abraham from murder (compare it with Rembrandt’s take on the theme a thousand years later).

Conveniently, there’s a combined ticket which provides access to the major sights, including the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia next door, the Baptistery of Neon, and the Archbishop's Chapel. (Die-hard fans of the early-Christian period could also trek out to the Mausoleum of Theodoric on Ravenna's outskirts.)

Piadina and Culatello in Ravenna

In Ravenna, it’s fitting that one should try a piadina, the local flatbread adopted from Byzantine and still popular here and a few nearby towns. I had a delicious version at a small shop called Profumo di Piadina, stuffed with cooked ham (prosciutto cotto) and squacquerone, the creamy local cheese. The version in nearby Urbino is called crescia, and call it piadina at your own risk! It was also in Ravenna, at the city's swanky market hall, Mercato Coperto, that I couldn't resist a few slices of aged culatello from a butcher I passed by.

Leon Battista Alberti in Rimini

Rimini is located less than an hour from Ravenna by train and I made a quick stop to see its early-Renaissance church – Tempio Malatestiano. The architect was Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), a father of the Renaissance, who was completely obsessed with Roman ruins. In the employ of Pope Nicholas V, he studied the ruins, drew the ruins, and published about the ruins. Not surprisingly, his own buildings resembled the gigantic complexes of ancient Rome. (Alberti designed few buildings, Mantua in Lombardy has two of them.)

Rimini’s mercenary lord, the ruthless Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta commissioned the church. Malatesta was an archrival of Federico Montefeltro in nearby Urbino (more on him below). Alberti’s contribution – work started in 1453 and never finished – is a thick marble encasement of an earlier Gothic structure. “Someone received a very good contract supplying all that marble,” wrote a friend when I sent him the photo above. The front of the church features a triumphal arch motif and there are deeply cut arcades on the sides. Heavy, solid, geometric masses, both impressive and intimidating.

The Gothic interior, which was badly damaged in WWII, is overlaid with a decorative program by VIP artists. Piero della Francesca painted the Malatesta family chapel, showing the lord proudly kneeling before his patron saint, Sigismund, accompanied by a duo of loyal greyhounds. That Crucifix hanging above the altar? By none other than Giotto di Bondone.

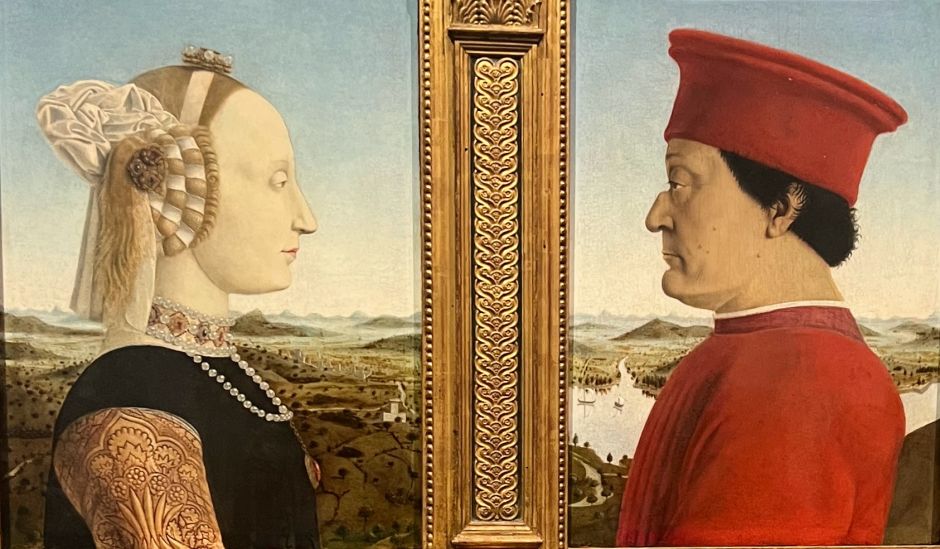

Federico da Montefeltro’s Urbino

Urbino is an astonishingly beautiful hilltop town about an hour’s drive from the Adriatic Sea. It was an important center of the Renaissance and a pinnacle of courtly elegance and culture under Duke Federico da Montefeltro (1422-1482). "Where wit and beauty learned their trade," wrote W.B. Yeats. Despite its small size, Urbino is still a very lively place thanks to its university, founded in 1506, which occupies seemingly every building in town. I wasn’t surprised when I read that there are more students (17,000) than residents (15,000) in Urbino.

Montefeltro was a colorful figure – part mercenary, part intellectual, but he liked to pose in full military armor on paintings. After losing his right eye in a battle, he had his nasal bridge removed by a doctor to improve his field of vision.

Raphael, perhaps the most famous painter in history, grew up in Urbino because his father, Giovanni Santi (1435-1494), worked for the Duke as a court painter. The Raphael Memorial House is a letdown. The bare three-story building features mediocre copies of his paintings and one remaining fresco in which Raphael may or may not have had a hand assisting his father.

The Ducal Palace & The Picture Gallery

Frequent visitors to Urbino’s Ducal Palace included leading architects (Leon Battista Alberti, Luciano Laurana, Francesco di Giorgio), painters (Piero della Francesca), and writers (Baldassare Castiglione). The 15th-century early-Renaissance building complex has since been gutted, but the remaining stone lintels, grand fireplaces, and the spectacular wooden paneling of Montefeltro’s study – with inlays showing the Masaccio-like deep perspectives that fascinated artists – provide a glimpse into its past.

Today, the palace houses the National Gallery of the Marche region. The most famous works are Piero della Francesca’s puzzling Flagellation of Christ (1470; there’s good explanatory text) and Raphael’s portrait of a noblewoman, La Muta (1508; with the gentlest hands I’ve seen in painting). There are many works by Federico Barocci, a painter from Urbino who stood at the threshold of the Baroque, fusing the styles of Raphael and Titian and impressing people like Peter Paul Rubens.

The exhibition includes a famous “Ideal City” painting by Luciano Laurana from 1475 – the streets and the buildings are laid out geometrically, but it's far from the soulless urban plan of Le Corbusier from 450 years later.

Atop the neighboring hill stands the Chiesa di San Bernardino, originally intended as the Montefeltro family mausoleum. The church is a half-hour-stroll from Urbino’s city center and a beautiful example of 15th-century early Renaissance: self-conscious about its geometric simplicity and planar surfaces (still holding the remains of Federico and his son, Guidobaldo).

Back in the old town, the Oratory of St. John the Baptist features a cycle of frescoes by a pair of local painters from the early 15th century. A hundred years after Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel and a hundred before Michelangelo’s Sistine, it’s a fascinating archive of art history – brilliant, clumsy, adorable.