You can't avoid them in Vienna. Seemingly every building, every church, every statue ties back to a Habsburg. Who were these people? Europe's greatest dynasty ruled much of Central Europe for 600-plus years, so what follows is inevitably as much about the family as it is about the whole region.

The Beginnings: Power At All Cost

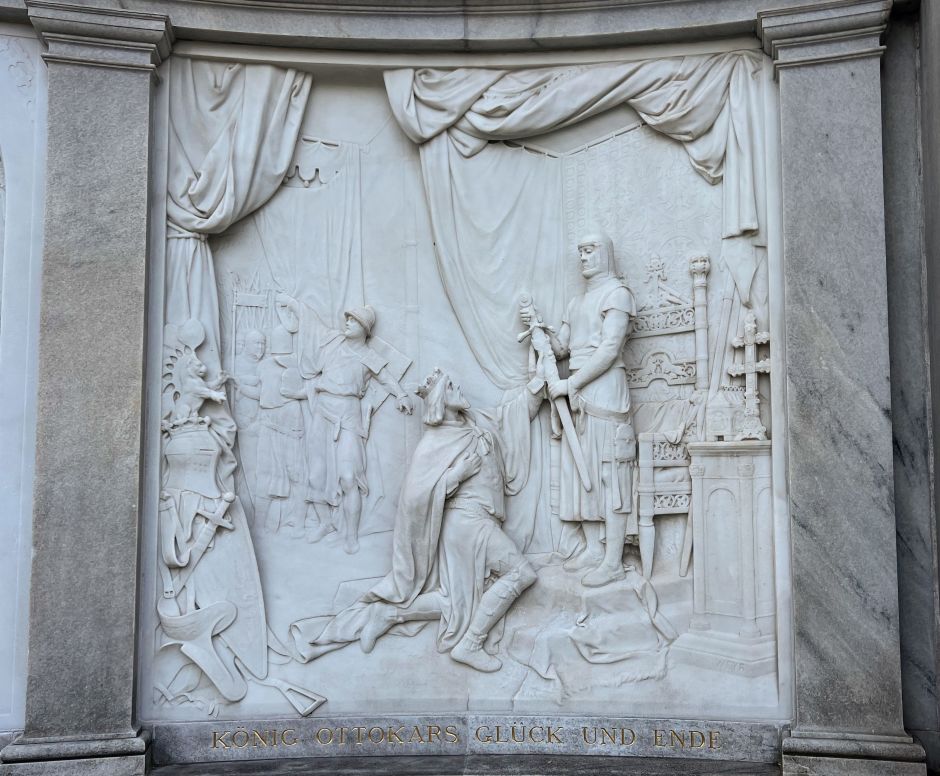

The first Habsburg to capture parts of today’s Austria was Count Rudolf, who seized the lands of the recently extinct Babenberg family. Rudolf defeated the powerful Bohemian (Czech) King Ottokar in 1278 at the battle of Marchfeld, then settled into the old Babenberg castle in Vienna, which was already an important port city along the Danube with direct access to Germany, Hungary, and the Byzantine Empire.

Before Marchfeld, the Habsburgs had been a mid-level noble family with territories in Upper Alsace and in present-day northern Switzerland. The original Habsburg castle, rather modestly sized, still stands near the highway between Zurich and Basel. With Marchfeld, the family’s power base shifted to Austria, in the southeast corner of Germany, known then as the Holy Roman Empire.

Rudolf’s successors added new territories to the Habsburg base throughout the 14th century, including present-day Slovenia and the rugged Alpine terrains of Tyrol. At this point, Habsburg dynastic success owed much to sheer luck – staying alive and producing children who reached adulthood was a constant challenge in medieval Europe – and to ruthless opportunism. Duke Habsburg Rudolf IV, for example, forged in 1359 a collection of "historic" documents, Privilegium maius, which resulted in the family being elevated to the highest rank in the Empire with privileges to match (they became Archdukes).

It was after the extinction of the Luxemburg family that the Habsburgs took over German imperial politics. In 1440, Frederick III became Holy Roman Emperor, a position the Habsburgs basically retained until the Empire’s collapse in 1806. To be clear, the Habsburgs had lands within the Holy Roman Empire that they held directly, such as the Austrian territories and later Bohemia, and on top of this, as emperors, all states in the Holy Roman Empire were their imperial vassals.

However, by this point the Empire was a loose – and progressively looser – association of decentralized German states that were only nominally united by the elected Habsburg emperors. Being an emperor was about prestige and soft power rather than hard cash. In the meantime, ironically, the Habsburgs lost their original territories in Switzerland as the cantons banded together and expelled them even from the old family fortress by 1415.

The Greatest Matchmaker: Maximilian I

The skillful diplomacy and the extraordinary luck of Emperor Maximilian I brought most of Europe under the Habsburg's sway. In 1477, Maximilian married Mary, daughter of Charles the Bold, the deceased Duke of Burgundy, thereby gaining the wealthiest region of Europe – the Low Countries: today’s Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg. In 1496, he wed his son Philip to Joanna, daughter of the Queen of Castile and King of Aragonia. After the unexpected deaths of Joanna’s brother, older sister, and nephew, the Habsburgs earned the recently united Spain with its New World possessions as well as Sicily and southern Italy.

Closer to home, Maximilian devised a double marriage scheme between his grandchildren and the Jagiellonian royal house. This meant that after the 1526 death of King Louis at the battle of Mohács, both Hungary (today’s Hungary, Croatia, Slovakia, and parts of Romania, Serbia, and Ukraine) and greater Bohemia (today's Czechia) fell into the Habsburg’s lap. Hence the well-known saying coined by Hungary's Renaissance King, Matthias Corvinus: “Let others wage war, you, happy Austria, marry.”

The Habsburgs now had territories that fell outside the borders of Germany (Holy Roman Empire), such as Hungary. Going forward, I'll refer to the Holy Roman Empire as "Empire," and to the Habsburg's directly-held lands – Austria, Bohemia, and Hungary – as the "Habsburg Monarchy." Spain and the Low Countries I treat separately.

Spanish Side, Austrian Side

Habsburg power peaked under Maximilian’s older grandson, Charles V (1500-1558), who seriously entertained the idea of a universal monarchy – ruling the entire world. Like most Habsburg emperors, Charles wasn’t especially bright but fueled by a divine mission to unite Christendom under the Habsburg dynasty’s god-given primacy. What prevented him was a solidly independent France and an ever-stronger Ottoman Empire encroaching on Europe. Worse, Europe had just turned upside down after the Augustinian priest, Martin Luther, posted in 1517 his heretical 95 theses on a church door in Saxony.

Protestantism spread so quickly that within a couple of decades most people in the Empire (including Austria and Bohemia) and in Hungary were on the side of the Reformation. The Catholic Habsburgs became a small minority within their own dominions. Charles, based out of Madrid, realized that his empire was too vast to effectively deal with the double-threat of Protestantism and the Ottomans while also fighting France closer to home (it took months to reach Vienna from Madrid). In 1556, he divided the Habsburg imperium between his son Philip and his brother Ferdinand.

Philip received Spain and the Low Countries; to Ferdinand went Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, and the nominal leadership of the Holy Roman Empire. There was no doubt as to who got the shorter end of the stick. The Austrian side was poorer and with bleak commercial prospects as trade shifted to the Atlantic and the New World. Bloody religious wars between Catholics and Protestants already plagued the Empire. In addition, Ottoman Turkey seized most of Hungary in 1526, leaving only a sliver on its western and northern borders for the Habsburgs and threatening Vienna itself.

For reasons of dynastic survival, the Austrian and Spanish branches remained very close. It was standard practice in Vienna, for example, to send the Habsburg children to Madrid for a few years to learn proper royal etiquette (Madrid had a grander court). First cousins were regularly married to each other and matchups between uncles and nieces were also common. The protruding “Habsburg jaw,” which can be studied on countless busts and Diego Velázquez-paintings in the Kunsthistorisches and the Prado museums, is the result of this inbreeding.

The Problems of Hungary and Bohemia

With Hungary and Bohemia, Ferdinand expanded its Austrian power base with a complex patchwork of territories. Each of these countries by then had a long-established nobility that prided itself on its autonomy and constitutional liberties. They had local parliaments (diets) that made laws and levied taxes, and feudal estates that administered those laws and collected those taxes. This meant that the Habsburgs were constantly at the mercy of these noble magnates for money and military support and had to be sensitive to their privileges and economic interests.

Furthermore, Hungary and Bohemia turned upside down the ethnic makeup of the Habsburg Monarchy. What had been an almost completely German-populated land – the Austrian territories, such as Upper and Lower Austria and Styria and Tyrol – suddenly became the most multiethnic state in Europe. The Hungarian Kingdom, for example, had sizable Hungarian, German, Slovak, Romanian, Croatian, Serbian, Jewish, and Ukrainian populations. Bohemia was majority Czech. Later, in the age of nationalism, this caused many headaches for the Habsburgs.

Governing such a diverse and decentralized state was an enormous challenge. It wasn’t until the late 18th century that a proper administrative center was formed in Vienna that suppressed and bypassed the still extensive bureaucracy of the feudal estates. The Habsburgs were at a major disadvantage compared with their main enemy, the French kings, who by then ruled a centralized and assimilated French state.

Perhaps due to these challenges, Ferdinand, and later his son Maximilian II and grandson Rudolf II, were far wiser rulers than their wealthier and more powerful cousins in Madrid. Unlike the militant, tyrannical catholicism the Spanish side came to be known for, those in Vienna preferred religious toleration and a peaceful coexistence between Catholics and Protestants. No doubt, this was in part a strategic move: they wanted to retain the unity of their territories and the military support of the Protestant nobles in the face of the Ottoman threat.

Emperor Rudolf II was an unusual case. He distinguished himself not with the notorious Habsburg piety and work ethic, but with a keen interest in alchemy, science, and strange objects. In 1583, he moved his court from Vienna to the castle of Prague (Hradčany) to be farther away from the Ottoman battle lines and surrounded himself by astronomers, for example Johannes Kepler, and artists. He had his Flemish court painter, Bartholomeus Spranger, decorate the imperial halls with a sequence of erotic canvases. He refused to follow the family protocol and marry his cousin, Habsburg Isabella, instead maintaining an affair with Katharina Strada, the granddaughter of his art dealer with whom he had six children. Rudolf's painting collection and his cabinet of curiosities – paper-thin agate and chalcedony bowls and Giambologna statuettes, for example – are part of the permanent exhibition of Vienna's Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Catholics Only

The era of relative religious freedom in the Austrian side ended in 1619 when the extremist Ferdinand II became emperor. What started as a Protestant resistance movement to Ferdinand’s aggressive catholicization in Prague snowballed into a brutal Europe-wide conflict – the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) – involving also the fanatical Spanish relatives and costing more than eight million lives.

The Peace of Westphalia was a major blow to both branches of the Habsburgs. For the Spanish side, it was another humiliation after the 1581 secession of its Dutch provinces – who, without Spain’s harassment, unleashed the most advanced mercantile economy in the world – and the 1588 loss of the Spanish Armada to England. Habsburg Spain, rapidly losing power, was overtaken by Bourbon France as the dominant force in Europe.

For the Austrian side, it meant a smaller and weaker and even more fragmented Germany (Holy Roman Empire). On paper, the German estates were still the Habsburg's imperial vassals but they were free to choose their religion and basically independent. Habsburg rule over Germany became truly nominal. As a result, they continued to retreat from German politics, turning their attention to the lands they ruled directly: Austria, Bohemia, and Hungary.

There, they managed to completely root out Protestantism through forced conversions and the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of people (less so in Hungary and its eastern region, Transylvania, which gained religious concessions through force). In Vienna, for example, which had been majority Lutheran – something hard to imagine today – the Habsburgs brutally confiscated the houses of rich merchants who refused to convert and simply gave them to loyal aristocrats, such as the Liechtenstein family.

The Jesuit order provided vital support in these Counter-Reformation crusades. They sent teachers, established churches, and took over the universities across the Habsburg Monarchy. They organized mass conversion ceremonies and processions in Protestant areas to sway people.

The Counter-Reformation was also a tool for political control: during this Catholic restoration, the Habsburgs ejected much of the old Protestant nobility from its lands and from the local parliaments in Bohemia and Hungary. The new guard, naturally, was not only Catholic but also more loyal and cooperative.

Deceptive Baroque Brilliance

The remainder of the 17th-century brought positive developments for Habsburg Austria. An allied European army successfully defended Vienna against the Ottoman siege of 1683, and, capitalizing on the momentum, chased the Ottomans out of Hungary and Transylvania. And while the Spanish Succession War ended the Habsburg line in Spain – Louis XIV’s grandson took over – Austria received as compensation a bunch of wealthy territories that had belonged to their cousins, for example the Spanish Netherlands (today’s Belgium) and most of Italy. With these territorial gains, the Habsburg Monarchy was stronger than ever and free from the Turkish threat.

The heavenly mission of the Habsburgs seemed to have come true: together with a restored Catholic church and an increasingly loyal high-nobility, they lorded over a peasantry that paid all taxes. In fact, the peasants' feudal obligations got much worse as a result of this alliance between the Habsburg court and the aristocracy. In most parts of the Monarchy, peasants had to spend as many as four days a week performing unpaid robot services – tilling their landlord’s land for free (up from about one day). They were also forbidden to move somewhere else. For any grievances, they could only turn to the district courts, which were also run by the nobility.

Another victim of this alliance: the urban population. Unlike France and England, the Habsburg Monarchy had few sizable cities because they faced unfair competition from the aristocracy, which forced its peasants to buy only products that were produced on the estate. The expulsion of Protestants and Jews added insult to injury, since many of them had been town dwellers.

The exuberant high-Baroque churches, imperial buildings, and residential palaces of the first half of the 18th century embody this symbiosis of court, clergy, and nobility. The Habsburgs relied on the Baroque style as a propaganda tool to parade their power and to express their religious devotion. Examples include the grand Karlskirche, the Court Library, and the spectacular Plague Column that still soars over Vienna's Graben, showing Emperor Leopold saving his people from the epidemic with divine support.

Famously religious, the Habsburgs also started a cult of the Virgin, turning the town of Mariazell into a major pilgrimage destination and erecting myriad Marien Columns (Mariensäule) such as the one on Vienna's Am Hof. The victorious Catholic Church built hundreds of Baroque churches in the early 1700s across the Habsburg Monarchy, which can be easily identified today by their onion-shaped spires.

The aristocracy pulled its weight too, commissioning lavish palaces from the court architects, Johann Berhard Fischer von Erlach and Johann Lukas von Hildebrand. Families such as the Esterházy, Liechtenstein, and Schwarzenberg proudly projected to the world their newfound prestige, wealth, and proximity to the Habsburg court. Vienna and its suburbs are still swarming with hundreds of these Baroque palazzos. Italian architects and painters were initially entrusted with the design plans – people such as Domenico Martinelli, Andrea Pozzo, and Sebastiano Ricci – before a homegrown set of artists emerged to disseminate the lessons across the Habsburg territories.

But the Baroque pomp and the elaborate courtly manners masked what Austria had become by the 1730s: outdated, decentralized, superstitious, and intolerant. Unlike contemporary England and France, the Habsburgs were completely opposed to the emerging ideas of the enlightenment and to modern centralized governance (they were also opposed to science and the intellectual fields, but liked to patronize music and opera). Driven by a Catholic zealotry and visceral antisemitism, the dull and arrogant Emperor Charles VI was still resettling Protestants from the Habsburg heartlands and expelling Jews. Acting against the state’s economic self-interest in such an obvious way was unusual in the age of reason.

Time for Change

By the 1730s, Prussia replaced France as the greatest threat for the Habsburg Monarchy’s survival. An increasingly powerful German state in the northeast of the Empire, the Protestant Prussia was known for its efficient central administration and strong military. In 1740, Prussia launched an attack on the Habsburgs, hoping to take advantage of the succession crisis that followed the death of Emperor Charles VI. His daughter, Maria Theresa, ultimately secured the throne for herself, but she lost crucial territories in northern Bohemia (Silesia) to Prussia. The war exposed two major weaknesses. One: despite the size of the Monarchy, state revenues were thin. Two: the Habsburg military was small, inefficient, and run by incompetent people.

Modernization of the state affairs could wait no longer. Emulating the enemy – the enlightened model state of Prussia – Empress Maria Theresa grudgingly agreed to a reform program led by her chancellors, Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz and later Wenzel Anton Kaunitz. In line with the enlightened theories of their time, they believed in a strong, secular, centralized state that improves the well-being of its people, including those of the peasants. To achieve this, they had to build a direct link to the peasants and reduce the influence of the feudal estates and the Catholic Church.

First, Haugwitz increased the tax contribution of each Habsburg territory and demanded that the nobility pay part of the costs. The new revenues were spent on the military and on boosting the size of the civil administration, whose members now started to replace the estates' local agents. To avoid the exploitation of peasants, Kaunitz created land registries and took measures to standardize the feudal obligations. He maximized the amount of robot work and launched pilot programs with the goal of abolishing serfdom.

Maria Theresa’s advisors thought that the church was a barrier to progress, keeping people ignorant and superstitious. As a legacy of the Counter-Reformation, people spent too much time attending religious processions and responded only to visual persuasion. Kaunitz preferred a simpler, modest form of Catholicism that emphasized social responsibility.

He believed this could be achieved via mandatory elementary education, which would also provide vocational skills and ultimately increase state revenues. He dismissed the Jesuit methods of religious devotion and rote learning, focusing instead on morality, reason, and knowledge. When Pope Clement abolished the Jesuit order in 1773 for its undue influence, Kaunitz ordered all Jesuit property be confiscated to help pay for the roll-out of a public school system. By the end of Maria Theresa's reign, more than 6,000 schools opened across the Habsburg Monarchy.

In 1772, the Habsburg Monarchy participated in the first partition of Poland, adding southern Poland (Galicia) to its dominions with its mix of Polish and Ukrainian population. The empress was initially reluctant, but her first-born son and co-regent, Joseph, and Kaunitz convinced her that it was needed to keep up with the expansionist Prussia and Russia.

There's a giant Maria Theresa monument in Vienna today and people generally remember her as a good ruler. True, with the help of brilliant ministers – she was famously good at judging talent – she successfully transformed the Monarchy to meet the demands of the time. She laid the foundations of a modern centralized state. She built a solid military, a well-functioning bureaucracy, a public education system. She took steps to stop the exploitation of the peasants, although she avoided confrontation with the aristocracy. Paradoxically, she remained an arch-Catholic who persecuted Protestants, despised Jews, and was fundamentally against the ideals of the Enlightenment.

An Unusual Habsburg: The Enlightened Joseph II

Joseph II, who ruled between 1780 and 1790, was an atypical Habsburg. Unlike most of his ancestors, he was extremely intelligent and learned, and couldn't wait to launch the enlightened policies he thought his mother (Maria Theresa) was too timid to implement. Radically for a monarch, he truly believed in the equality of people and traveled the countryside incognito to meet peasants and understand their concerns, even trying his hand at tilling the land. He was also a control freak, had no political skills, and thought he knew what's best for everyone. His motto: “Everything for the people, nothing by the people.” Bypassing the local parliaments, he governed only through decrees, churning them out at a lightning speed.

He shut down hundreds of “unproductive” and “idle” Catholic monasteries that lacked schools, farms, or hospitals, using their wealth to build parish churches that served their communities with better educated priests and novices. He subordinated the Catholic Church to the state, which now controlled all clerical appointments. This earned him a protest-visit from Pius VI (he received the Pope in Vienna with utmost respect and refused to budge). He banned Catholic processions and cut the number of religious holidays. His Toleration Edict allowed Protestants, Orthodox Christians, and Jews to build places of worship and practice their religion.

His radical agrarian reforms ended the mandatory robot services, permitted peasants to move freely, and capped their taxes. In turn, he started to tax the nobility, rescinding their cherished centuries-old privileges. He opened the world’s largest general hospital in Vienna, built new schools, and created public parks, for example Vienna's Prater. He reformed the legal system with a new civil and criminal code under the concept of equality before the law. Torture was abolished and peasants received free legal aid in litigations against their landlords.

While Joseph was hailed as a folk hero among peasants and had many fans among middle-class intellectuals, such as Mozart and the young Beethoven, his idealist reforms completely ignored the traditional pillars of Habsburg power: the church and the landed aristocracy. Not to mention his countless infringements on personal freedom that frustrated a broad segment of society. He banned, for example, the use of caskets for burials (to save wood) and decreed what people could wear and where they could travel.

Predictably, the aristocracy reacted with armed rebellions and crisis erupted from Belgium to Hungary by the time of Joseph's death in 1790. His brother Leopold, the new emperor, was similarly reform-minded but wiser and more conciliatory. To restore order, he reinstated the nobility's tax exemptions and pulled back the abolition of the robot labor.

But he preserved most of Joseph's progressive achievements: more freedom for the peasants and for religious minorities; a fairer civil and criminal code; a more secular church that served its people; a healthy and liberalized economy; a strong military; a meritocratic system of state administration; and a rising middle class of educated bureaucrats in cities such as Vienna, Milan, Brussels, Prague, and Buda-Pest. Thanks to half a century of reforms by Maria Theresa and Joseph, the Habsburg Monarchy's peasants now looked to the state as their ally and a counterweight to the power of the local nobility.

A Weak Habsburg: Francis

Leopold soon died and his son Francis took over as emperor in 1792. He was a famously indecisive and narrow-minded ruler whose 43 years in power were shaped by the events of the French Revolution. Instead of continuing the enlightened reforms of Joseph and Leopold – his uncle and his father – Francis reverted to the safety of the feudal order. He wanted to gain the support of the aristocracy during his drawn-out war with Napoleon's France and he also dreaded what further enlightened progress might bring (Marie Antoinette, the executed queen of France, was his aunt).

The first half of Francis's reign was taken up by the Napoleonic Wars, a long sequence of military defeats and humiliations: Napoleon captured Vienna and the Habsburg Monarchy became a French satellite; Francis was forced to dissolve the Holy Roman Empire after Napoleon allied with himself most of Germany (1806); and he had to watch the low-born Bonaparte marrying his own daughter, Habsburg Marie Louise (1810).

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 restored the old order and even improved the Habsburg geopolitical position: the Monarchy gained Salzburg and Dalmatia and swapped Belgium for what used to be the Venetian Republic, thus creating a strong and unified central European state also in charge of northern Italy (Lombardy and Tuscany had already been Habsburg). Austria became President of the German Confederation, which replaced the Holy Roman Empire. These gains owed much to the shrewd negotiation of Klemens von Metternich, Francis’s loyal foreign minister and chancellor.

But there was no return to the social progress and meritocratic system of Joseph and Leopold. Francis and Metternich built a repressive state in which censorship and police informers infiltrated every layer of society. They halted the land and the tax reforms, so peasants were once again exploited and paid most taxes. They scaled back university and high school education and demanded that all state bureaucrats swear an annual oath of loyalty. Despite financing much of the economy – the railways, for example – Jews were still without equal rights and humiliated in many regions.

Francis and Metternich resented the liberal idea of a constitution and power shared with the people, so they governed without consulting the regional parliaments. Internationally, Austria was viewed as the enemy of social progress, a place of reactionary conservatism. Many people left for other parts of Germany and visitors to Vienna would regularly point out the lack of intellectuals and writers in the city. The so-called Biedermeier culture with its inward-turning domesticity and escape to nature – depicted in the cabinet paintings of Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, Peter Fendi, and Josef Danhauser – embodied the illiberal and anti-intellectual decades of the 1820s and 1830s. Through literary salons, coffeehouse groups, and civil societies, the middle classes tried to fill the void left by the state.

Still, Francis's wasn't a complete reversal of the previous epoch. He insisted on the rule of law and took advantage of the industrial age with the liberalization of the largely guild-based economy. With imported machines and technologies from England, the textile and iron industries grew significantly and this was when railways appeared across the Habsburg Monarchy. Technical education began in 1815 with the founding of today’s Vienna University of Technology.

The Forces of Liberal Nationalism and 1848

Originating in France, the revolutions of 1848 reached all parts of the Habsburg Monarchy and brought a climactic end to the Metternich era. People were overjoyed and filled with optimism, from Milan to Venice to Vienna to Prague to Buda-Pest. But the revolution meant different things to different people in the Monarchy. The peasants, for example, wanted the abolition of their feudal duties; the emerging factory workers in the cities' slums wanted better working conditions and no more child labor; the urban middle classes wanted a liberal constitution and a representative parliament. In addition, there was now a complex system of competing national interests.

The 19th century saw the emergence of Romantic nationalism – the idea that people who shared a language or ethnic background also shared a national consciousness. This Romantic notion gradually hardened into demands for political independence and burst to the surface during the revolutions of 1848, creating new alliances, new dilemmas, and many contradictions in the multi-ethnic Habsburg Monarchy.

Germans in Bohemia discriminated against the Czechs, the Poles in Galicia against the Ukrainians, the Slovenians in Gorizia against the Italians, while the Hungarians altogether broke from the Habsburg Monarchy, but without support from Croatia, which wanted its own independence after centuries of submission to Hungary. There was also the issue of the Habsburg Monarchy versus Germany. German liberals wanted a united Germany based on the territories that had been part of the Holy Roman Empire, including Bohemia, but the Czech liberals opposed this, because they didn’t think Bohemia belonged to Germany – they wanted Bohemia either part of the Habsburg Monarchy or as an independent Czech nation.

The national revolutions of 1848 raised new questions: Were people’s primary loyalties to their national groups (Czechs, Germans, Poles, etc.), to their historical territory (Bohemia, Upper Austria, Galicia, etc.), or to the Habsburg Monarchy itself? Was a nation defined by its language, ethnic group, or crown land? Was there an Austrian nation? If so, was it German or Slav? Could a person belong to more than one nation?

Initially, the Habsburg court agreed to most of the revolutionary demands. In July 1848, for the first time, an Austrian Imperial Parliament was summoned. The parliament was elected democratically by people from across the Habsburg Monarchy (without Italy and Hungary, which were consumed by independence wars). The new parliament abolished the feudal structures and ended the peasants’ robot requirements. It also approved the use of national languages in the civil administration and a bill of rights that guaranteed individual freedoms that were missing during the Metternich era – freedom of religion, speech, and assembly.

Dreaming Absolutism: The Young Franz Joseph

After the military put down the revolutions in Italy and Hungary in 1849, the new emperor, 18-year-old Franz Joseph, swept all questions of constitution and national rights under the rug. He felt secure enough in his power to dismiss the revolutionary central parliament together with all regional diets and, going against the currents of his time, impose a radical absolutism. He aggressively centralized and modernized the state bureaucracy down to the district level, from Milan all the way to Transylvania, and ruled only by decrees. For swift enforcement, he relied on his beefed-up administration as well as the police and the army.

Containing many forward-looking elements, Franz Joseph’s absolutism was closer in spirit to the ambitions of Joseph II than those of Francis and Metternich. For example, he accepted the full emancipation of the peasants – passed by the revolutionary parliament – and ended tax exemptions for the nobility. He boosted the economy with the creation of a single market across all Habsburg territories and extended and liberalized the railways. He founded the Creditanstalt bank to finance industrial investments with long-term loans. He improved the universities whose graduates became competent members of the state bureaucracy.

The exception from this progressive agenda was his religious policy: Franz Joseph’s faith was so deep – and his mother's influence so great – that in 1855 he gave up state control of the Catholic church. To the outrage of intellectuals and liberals, this meant that the church was once more in charge of elementary school education and it adjudicated mixed marriages.

Franz Joseph often visited his far-flung territories to counter his negative image of a tyrant who got rid of the constitution and the parliament (railways made travel a lot easier). He capitalized on the popularity of his beautiful and free-spirited wife, Elisabeth, better-known as Sisi, who was especially well-liked in Hungary. This helped to moderate resentment there toward Franz Joseph, who ordered the execution of Hungary’s revolutionary heroes in 1849.

Crucial defeats on the battlefield, however, forced the bellicose young emperor to cut short his absolutist dream. In 1859, Franz Joseph lost all Habsburg territories in Italy to a Franco-Piedmontese alliance that unified Italy (risorgimento), now completely without Habsburg involvement. The 1866 loss to Prussia at the battle of Königgrätz meant that it was not the Habsburg Monarchy but Prussia that would unify Germany. As a crushing humiliation, Habsburg Austria wasn’t even invited to join the new German Empire.

Austria-Hungary: The Great Transformation

Before events could cascade further out of control, Franz Joseph quickly gave in to Hungary's demands for separation. Hungary wanted a constitutional kingdom that was independent from Austria, having its own central parliament in Budapest, own ministries, own state bureaucracy. This Hungarian Kingdom included today's Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia, and parts of Austria, Romania, Serbia, and Ukraine (within Hungary, Croatia retained its semi-independent parliament, the Sabor).

Hungary's remaining connection with the rest of the Monarchy would be through a single market and currency, a joint foreign policy and military, and through Franz Joseph himself, who became King of Hungary and Emperor of Austria. Every ten years, delegations of the Budapest and the Vienna parliaments would negotiate the budget of the common expenses. Thus formed in 1867 Austria-Hungary, or the Dual Monarchy. No longer a great power of first rank, but still significant.

By then, Franz Joseph was forced to concede also to the Austrian side, which included today's Austria, Czech Republic, Slovenia, and parts of Italy, Poland, and Ukraine. The wars had bankrupted the state and the banks told Franz Joseph that any financing was conditional on an elected central parliament and a constitution with strong limitations on his imperial power. He had no choice. The first session of the Austrian central parliament was held in 1861. Franz Joseph retained control over foreign policy and the military and the governments were responsible to him (he hired and fired the ministers). Still, he no longer made laws and lost control over the budget.

Understandably, the Czechs, Poles, Slovenians, and other nationalities of the Monarchy weren’t happy about the formation of Austria-Hungary, but they viewed it as a temporary constitutional victory for ethnic Germans and Hungarians. Nationalist tensions continued to burden both sides of Austria-Hungary during its fifty years of existence (1867-1918). Things could get famously chaotic in the Austrian central parliament, where conflicts between German and Czech nationalists resulted in endless obstructions. They fought over representation and over the official language in schools and in the civil administration in Bohemia, with Germans insisting on keeping German the only official language.

The Hungarian side was calmer but less democratic. The ruling Liberal-Nationalist Party prevented non-Hungarians from gaining representation in the central parliament by tying voting rights to income levels (most Slovaks and Romanians were poor peasants). Since Hungarians comprised less than fifty percent of the country, there was a relentless effort of cultural and linguistic Hungarianization – the system favored those who spoke Hungarian. They had a much better chance of finding employment as state bureaucrats, for example, even in communes where the population wasn’t Hungarian.

The situation was different with Jews, who became completely assimilated, more so than anywhere else in Central and Eastern Europe. They went on to form a symbiotic relationship with the Hungarian political elite, which relied on them to transform Hungary into a modern capitalist state. In exchange, they granted them full civil rights and crushed anti-semitism.

It was a known fact that Franz Joseph lacked charm and was indifferent to intellectual stimulus, to art, to books. By all accounts he was a bore. But over time he came to be viewed as a solid and reliable anchor in an otherwise fast-changing Dual Monarchy. Rising at 4:30 a.m. and laboring away all day between rushed meals, he was the dutiful, disciplined, first civil servant of the state. Nobody questioned his personal integrity. His private letters even reveal a capacity for tenderness and – most of all – a profound loneliness (Sisi, selfish and disillusioned by the Vienna court, spent most of her time away traveling).

Accordingly, Franz Joseph’s reputation went from being a hated military-obsessed autocrat to a widely respected arch-grandfather who earned the loyalty of the people. Part of this loyalty stemmed from his long reign – he embodied Austria-Hungary – and from the fact that people sympathized with the personal tragedies that afflicted his life, such as the murder of Sisi and the suicide of his son, Rudolf. Tyrolian peasants in the Alps, Czech businessmen in Bohemia, Hungarian nobles in the Alföld, and Jewish merchants in Galicia equally mourned his passing in 1916 after 68 years in power.

There were valid reasons for that. Franz Joseph oversaw the greatest transformation in the history of the Habsburg Monarchy. Austria-Hungary became a place where Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Croats, Serbs, Slovaks, Romanians, Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, Slovenians, and Italians lived in security, peace, and increasing prosperity. Where the economy was rapidly integrating and catching up with the most advanced countries in Western Europe. Where heavy investments in education yielded the most extensive school system in Europe. Where voting rights, at least on the Austrian side, were among the most democratic in the world by 1907.

This was the period when Vienna, Budapest, Prague, and Trieste grew into cosmopolitan cities and great cultural centers, producing many scientists, philosophers, and writers. These were the cities of Gustav Mahler, Béla Bartók, Arnold Schönberg, Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos, Sigmund Freud, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Karl Polányi, Arthur Schnitzler, and Franz Kafka. For the first time, a Habsburg country was known for its intellectual achievements, not just its music.

Many of these developments harked back to the sizable Jewish population of Austria-Hungary (ten percent in Vienna, more than twenty in Budapest). Better educated than everyone else and no longer persecuted, Jews quickly adapted to the demands of the modern economy and came to be radically overrepresented in middle-class professions – doctors, lawyers, journalists – in addition to their traditional fields of banking and commerce. Envy and hatred predictably followed, but, as mentioned above, Franz Joseph fought antisemitism, even sending in the military when needed. In Hungary, he was successful, in Austria, less so.

Lessons Learned and Not Learned

Austria-Hungary collapsed in 1918 because of World War I. With it collapsed the Habsburg dynasty, after lording over Austria for more than 600 years. For much of the 20th century, the disappearance of the Dual Monarchy was viewed as inevitable – something waiting to happen given its simmering national conflicts. Since the 1980s, historians have corrected this view. The majority today thinks that it was quite the opposite: a healthy multi-ethnic and multi-cultural state that enjoyed the attachment of its people.

The political and cultural grievances, they say, were the reflections of a functioning democracy whose different peoples and cultures felt they could shape its future. There was never any internal pressure to break up. All nationalities were loyal to the Dual Monarchy and imagined their future inside of it. That Czech nationalists subverted the war efforts and refused to fight is a myth that was invented in post-war Czechoslovakia.

The collapse of Austria-Hungary is seen as all the more unfortunate when considering the disastrous history of the 13 nation-states that grew out of it: horrific treatment of ethnic minorities, descent into fascism and communism, modern-day nationalist autocracies. It’s hard to imagine that things could’ve gone worse.

In fact, here lies the Monarchy's important legacy: Austria-Hungary was the most diverse country in Europe and it provided safety and prosperity for its people. It was a protective haven for the small nationalities. Proof that a state with many constituent nations can co-exist. Austria-Hungary was the opposite of a nation state.

This is why historians today often point to its resemblances to the European Union. Far from perfect, annoyingly inefficient, but inclusive, diverse, operating based on the possibilities of compromise and a complex system of checks and balances. With a democratic leader who appreciates the uncertainties of policy and who avoids impulsive decision-making. Austria-Hungary was close to achieving that.

Unfortunately, Franz Joseph declared war on Serbia on July 28, 1914, rather than compromise on the South Slav question. He was certainly influenced by the reactionary aristocrats within the military establishment, who felt out of place in Austria-Hungary's merit-based and democratic society and hoped that war might revert things to the way they had been. Still, Franz Joseph started the war out of an irrational and antiquated sense of dynastic honor. He almost certainly knew he was starting a world war where millions would die, but too great was his “concern for his patrimonial legacy” to back down. He had to protect the honor of “his monarchy.” Perhaps what the Monarchy needed to survive was one fewer element – the Habsburgs themselves.

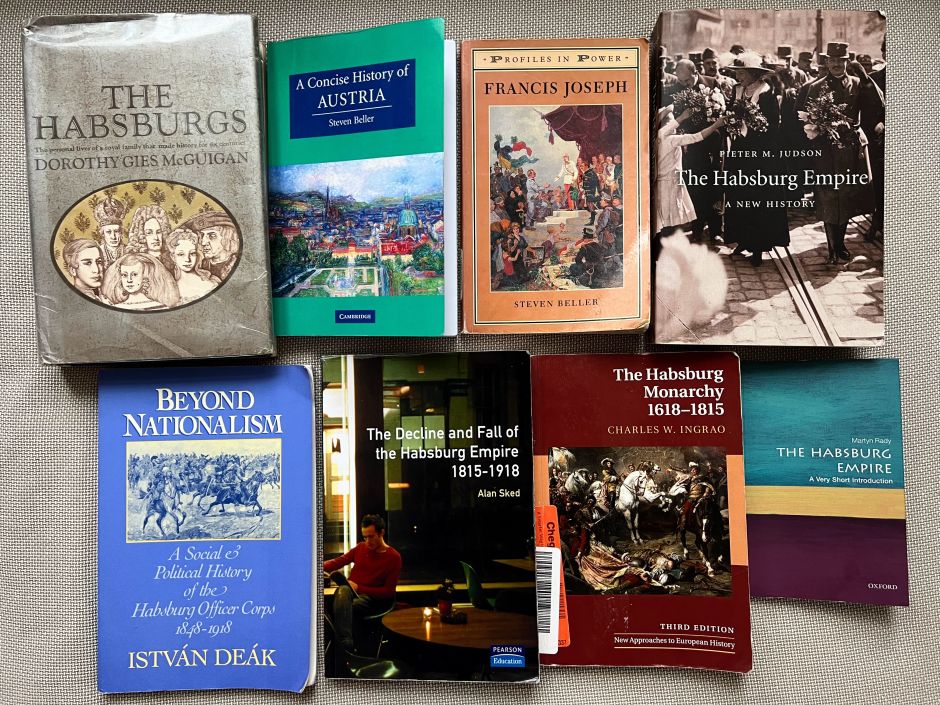

If you're interested in exploring Austrian and Habsburg history, I recommend the books of Steven Beller, especially the Concise History of Austria and Vienna and the Jews. Pieter M. Judson's The Habsburg Empire makes a convincing case for the Dual Monarchy especially in light of the nation states that succeeded it. Charles W. Ingrao’s The Habsburg Monarchy 1618-1815 is a lucid examination of the Counter-Reformation and the ensuing period of enlightened centralization. The late Columbia Professor, István Deák, wrote an insightful history of the Habsburg military corps: Beyond Nationalism. Dorothy Gies McGuigan's The Habsburgs is a light read on the personal sides of the royals.