Art historian Markus Kristan was the Albertina Museum's architecture curator between 1993 and 2022. He was responsible for the Adolf Loos archive and published numerous books about leading Austrian architects and designers, including Adolf Loos, Josef Hoffmann, and Oskar Marmorek.

Otto Wagner (1841-1918), a father of Viennese architecture. Who were his influences?

Karl Friedrich Schinkel. When Wagner studied in Berlin, his professor had been a colleague of Schinkel. The other big influence was Theophil Hansen, the most prolific architect of Vienna’s Ringstrasse. Hansen himself was shaped by Schinkel.

Wagner grew up seeing all the Theophil Hansen buildings in Vienna.

That too, but Hansen was also a family friend. The Wagners lived in a building in downtown Vienna designed by Hansen. He encouraged the young Otto to study architecture when he saw how well he drew. Wagner and Hansen had the same birthday, 28 years apart. Perhaps they celebrated birthday parties together.

That’s fun to imagine.

After Wagner finished university, he worked as Hansen’s construction manager. Wagner was sent off to projects Hansen didn’t have time to personally supervise, such as the Palais Epstein, right next to the Parliament, in the early 1870s. Otto Wagner, by the way, was very rich.

Good for him!

His mother inherited a lot of money which eventually landed with him. This is the reason Wagner usually owned the apartment-buildings he designed. 20-30 apartments, for example, in the famous Majolika and Medallion Houses on the Wienzeile. This meant he had much more liberty than other architects. His hands weren’t tied. No one could tell him, “I gave you the money, you have to do it in this style.”

What’s special about Wagner’s buildings?

I always feel it’s the proportions. He had a much better feeling for proportions than other architects. I don’t know why, since his training wasn’t that different. Sometimes he plays spatial tricks with the viewer. In Stadiongasse 6-8, he creates an illusion of space by narrowing the walls. Like Borromini. Josef Hoffmann also had this fine-tuned sense for proportions and so did Adolf Loos.

Wagner’s architecture took some turns.

1894 was an important year for him. First, he won the Vienna City Railway (Stadtbahn) commission. It was an enormous project for dozens of stations, bridges, viaducts. At times, Wagner employed a staff of 70. It was a technical, engineering challenge that had a big impact on his style and use of materials. This was when he started working with iron trusses, for example.

What else happened in 1894?

Karl von Hasenauer died and Wagner was appointed professor of architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna (Akademie der bildenden Künste). It was a rare case when the older teacher – Wagner was over 50 by then – was influenced by his students and young colleagues. Especially Joseph Maria Olbrich, who did many drawings for the railway. He did the famous station outside the emperor’s palace in Schönbrunn (Hofpavillion).

Olbrich left the city in 1899. It was a big loss for the Vienna art scene.

He went to start an artists’ colony in Germany’s Darmstadt by the invitation of Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig. Wagner wasn’t happy. He wanted Olbrich to stay in Vienna. He tried to get him a professorship at the University of Applied Arts and even offered the hand of one of his daughters. Alas.

Why wasn’t Wagner a founding member of the Secessionist group in 1897, as were his students?

The Secessionist artists broke from the Künstlerhaus, but this was an uncomfortable situation for Wagner, because a few years earlier members of the Künstlerhaus had supported him with the railway commission. I think he felt he would’ve betrayed them. So he waited a few years. That’s my theory.

His late buildings – Postsparkasse (1904-06) and 40 Neustiftgasse (1909-12) – seem like a synthesis of all that came before.

Wagner was a classical architect and that remained with him until the end. At the same time, he was very modern when it came to materials, using aluminum and reinforced concrete. With the Postsparkasse and the two houses in Neustiftgasse and Döblergasse, the architecture is more practical than anything he did before. Still, Wagner always managed to create extremely aesthetic buildings.

What’s your favorite Wagner building?

His public stations for the City Railway. Vienna is lucky to still have them.

Another heavyweight: Josef Hoffmann. He was Otto Wagner’s student and a founder of the Viennese Secession.

Hoffmann had many influences. His early period, with the fluid lines and nature motifs hark back to Henry van de Velde, the founder of the Belgian Art Nouveau, and Aubrey Beardsley. Two good examples are the interior of Paul Wittgenstein’s house in the Austrian countryside, and the Apollo candle store (Appendix, Abb. 86-88) in Vienna, both from 1899.

Adolf Loos hated them. He rejected the Art Nouveau style in favor of an elegant simplicity.

Of course… It’s the same year that Loos did the Cafe Museum, which looked very different.

Hoffmann completely changed his style around this time. He went from curvilinear to simple and geometric. Why?

Adolf Loos claims that Hoffmann’s conversion moment happened when the two of them visited the interior Loos designed at 18 Landesgerichtsstraße…Who knows. In 1900, the Secessionists staged an exhibition for the Glasgow Four, including Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald. This surely had a big impact on Hoffmann.

Hoffmann’s style kept evolving.

Hoffmann often changed his style. When the young Dagobert Peche appeared on the scene in 1915, Hoffmann switched to Baroque and Rococo. It was again one of those things when the student shapes the master. Loos was more consistent.

Hoffmann was one of the three founders of the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903.

The Wiener Werkstätte was a workshop specializing in handcrafted household products. Dishware, furniture, lamps, jewelry, textiles, vases, book binding. This idea of Gesamtkunstwerk came from England, from the Arts & Crafts movement and William Morris. Adolf Loos spent decades attacking the Wiener Werkstätte and Hoffmann in particular.

What was Loos’s problem?

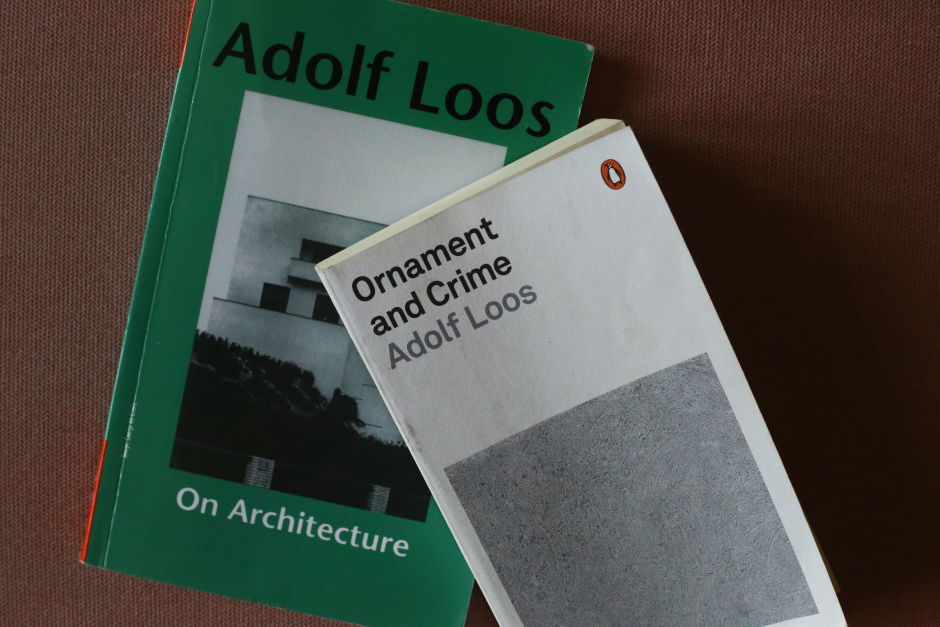

The difference between Hoffmann and Loos was that Hoffmann and his friends wanted to invent a new style and turned completely away from tradition. Loos, on the other hand, believed in the traditions of architecture. He dismissed the buildings of his immediate predecessors, the historicist Ringstrasse architects, but he loved Classicism and the Biedermeier.

What about his trip to America?

Loos was strongly influenced by American architecture – he was one of the few architects of his generation to spend a long time in the United States (1893 to 1896). He visited the Chicago World Fair of 1893 and saw all the skyscrapers of Sullivan and others.

He came back to Vienna in 1897.

And had nothing to do. He started working as a journalist. He met the writers Karl Kraus and Peter Altenberg, both of whom influenced his writing and became close friends.

I love how Loos treats materials.

His father was a stonemason. You should look at his handling of stone on his buildings. Where and how the materials meet. Everything is always exact. He was very picky about buying marble. Not all Cipollino marble is as beautiful as the one we see on the Looshaus. It was his hobby to visit newly discovered stone quarries across Europe.

Can you talk about his famous Raumplan?

He no longer simply layered one floor on top of another, but designed complex spatial situations in which each room was assigned the height it needed to function properly. He created pioneering buildings.

There was a fierce rivalry between Loos and Hoffmann, the two most famous Austrian architects at the time.

They were the same age, both born in 1870, and classmates in Brno (Brünn). Their rivalry started in Vienna, around 1900. We’re lucky for this rivalry, because they pushed each other. We have the fruits of their battle. Hoffmann wasn’t as confrontational toward Loos. His hands were full. He was a professor at the University of Fine Arts and had lots of private and public commissions. But as an architect, Loos was much more important I think.

Loos wrote polemics about everything from men’s shoes to women’s hats. He also had a particular diet. Can you talk about this?

Loos had a problem with his stomach from the constant stress and criticism. To cure this, he created his own diet: in his expensive, tailored suits, he always carried a piece of ham and a carton of cream. Doctors have confirmed to me that this self-invented diet, although fatty, can have a soothing effect on the stomach.

Loos didn’t like the Bauhaus. Why?

As I said before, Loos comes from the classical tradition. He wasn’t a purist. If his clients wanted to keep the old family furniture, he was fine with that. For him, atmosphere was important. His interiors weren’t as cold as Bauhaus apartments.

In 1928, Loos was sued for pedophilia. He received a light, suspended sentence amid murky circumstances. How does this change his legacy?

We need to be a little bit careful with passing judgment. First, we still don’t really know what happened. Second, by then Loos suffered from dementia as a result of the syphilis he contracted as a young man. If he really did what he was accused of, this is of course a terrible crime.

You’ve also written about lesser known Austrian architects. Who is Joseph Urban (1872-1933)?

He was responsible for the parade celebrating Franz Joseph’s 60th year as emperor in 1908. He designed the stage for the emperor and all the aristocrats, outside the Imperial Gate (Burgtor) in Vienna. But he was a little bit corrupt.

Oh no.

Joseph Urban received kickbacks from the carpenters who built the emperor's stage. He had a lavish lifestyle and needed money. He loved caviar, big cigars, that sort of thing. When he was found out, he couldn’t get new commissions in Vienna and emigrated to America in 1911. There, he became stage designer at the Boston Opera, then chief designer at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. And he built Mar-a-Lago, which is now owned by Trump.