Away from the fashionable parts of the lake, Keszthely is the cultural capital of Balaton and packed with treasures.

Often referred to as the “Hungarian sea,” Balaton is Central Europe’s biggest lake and the number one summer destination for people in Hungary. Most of its 200-kilometer (125-mile) shoreline is lined with vacation homes and beaches today, but before Balaton turned into a mass resort starting in the late 19th century, it was a sleepy region covered with vineyards and fishing villages.

Keszthely And Its Very Special Church

Balaton's one sizable town was Keszthely, at the westernmost end of the lake and cradled by the Keszthely Hills. A prosperous city already in medieval times, a vast 14th-century church still anchors the downtown and features the biggest Gothic fresco in all of Hungary today. The adorably clumsy scenes of the life of Jesus and the Virgin Mary were discovered in 1974 during a routine renovation and visitors can view them for free.

To the right of the altar is the red marble wall tomb of Hungary's (and Keszthely's) most powerful medieval feudal landlord: István Lackfi. His wealth started to rival that of the King of Hungary – Sigismund, later also the Holy Roman Emperor – who thought it prudent to get rid of Lackfi, which he did in characteristically medieval fashion in 1397.

The Festetics Legacy

The church has another important tomb located to the left of the altar: the marble pyramid attached to the wall contains the remains of the first member of the family whose name has become synonymous with Keszthely – the Festetics. It was a major turning point for the city when in 1739 Kristóf Festetics became the feudal landlord and established Keszthely as the center of his dominions.

Enjoying the patronage of the Habsburg court, the Festetics were among the wealthiest in the country, with 40,000 hectares (100,000 acres) of land across western Hungary. This was good news for Keszthely since they spent much of that money locally. The enlightened György Festetics (1755-1819), for example, built schools, a library, a printing press, and supported local artists and businesses. He built the biggest ever sailing boat of Balaton, the Phoenix, and he was the first to develop the nearby Hévíz, a large thermal lake available for swimming and a popular healing resort today.

He also founded Georgikon, the first college of agriculture in Europe. The Revolution of 1848 wiped out the institution, but its immense Baroque facilities house the Georgikon Museum today with a charmingly obsolete but rich collection ranging from the world’s first tractors to artifacts about winemaking, animal farming, and village life. It’s worth remembering though – as the museum also shows – that local serfs and peasants lived in abject poverty and some of the Festeticses, including György himself, were less than benevolent landlords.

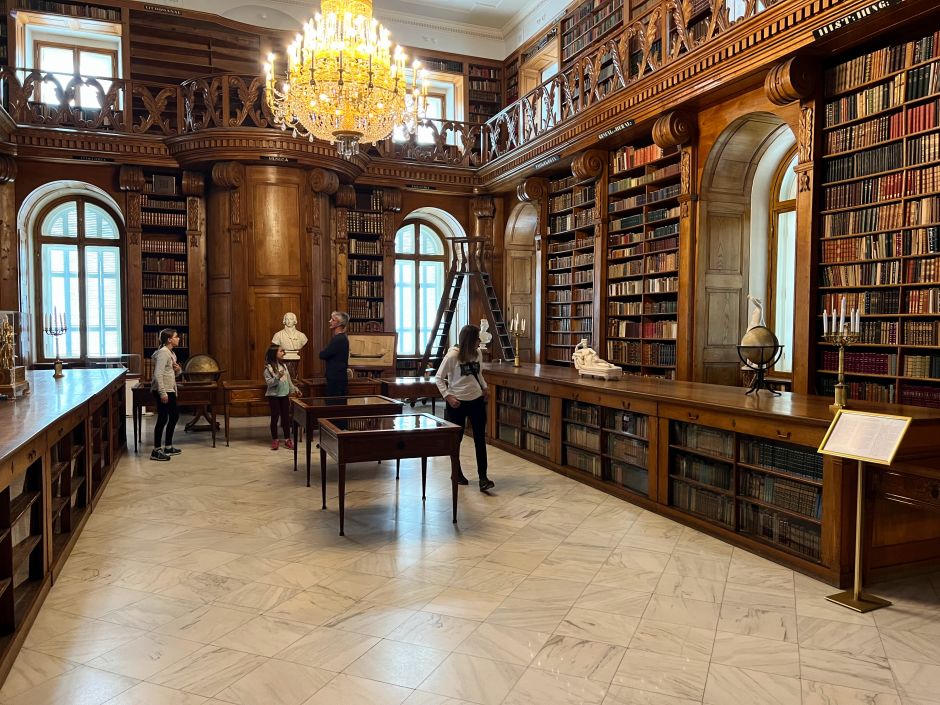

Perched above the city, the enormous, 101-room Festetics palace functions as a museum currently. In its heyday, the European high society often gathered here, including the Prince of Wales and Archduke Franz Ferdinand (whose later assassination triggered World War I). The truly jaw-dropping halls were decorated with David Teniers's goblins, Antonio Canova's statuettes, oversized Meissen porcelain vases, as well as furniture and lighting fixtures ordered from leading Parisian and Viennese manufacturers (some of them still there).

Owing to a small miracle, the palace’s beautiful neoclassical library (1801) escaped the looting of Soviet troops during WWII – the general of the invading Soviet army, Ilja Illarinovics Sevcsenko, was a historian who understood its immense cultural value and stopped his troops from ravaging the library by walling if off with a large “contagious diseases” sign emblazoned on it.

As with other royalty in Hungary, the state confiscated and nationalized all Festetics property in 1945 and the family fled from Hungary before the Communist takeover. The palace's manicured park is open for all to explore, though only a sliver of the original English garden has remained after the Communist state built a military barack in the rear side (split off by a motorway).

One of the last patriarchs of the Festetics clan was Tasziló (1850-1933), a cartoonish figure in his reverence for the Habsburgs and fondness for horse racing. After the collapse of Austria-Hungary in 1918, he made a point of snubbing Miklós Horthy, Hungary’s longtime leader between the world wars (Horthy wasn’t allowed to take the grand mahogany staircase of the palace, being too lowly of birth). Tasziló married Princess Mary Victoria Hamilton, the ex-wife of Albert I, the Prince of Monaco. The couple’s exuberant mausoleum hides in the back of Keszthely’s St. Nicolaus cemetery.

Tasziló’s lavish horse breeding farm in Fenékpuszta, just outside the city, was home to a collection of renowned thoroughbreds and the wonder of foreign visitors. Today, the facilities are under renovation but still worth a glimpse in part for the nearby remains of Valcum, the ancient Roman fortification built in the 4th century CE.

No one can blame Tasziló and Princess Mary for lacking good taste: they commuted between the palace and the horse farm through a hauntingly beautiful, six-kilometer (four-mile) pathway (allée) lined with black pines, today a popular hangout for dog owners.

More Things to Do in Keszthely

Keszthely is far from the well-off Budapest crowd: it takes two hours to reach by car, more than other parts of Balaton. In fact, Keszthely’s post-Communist history – after 1990 – hasn’t been a success story. The city used to be a bustling summer destination for East German tourists, but today vacation resorts in Spain or Italy offer more allure. Unattractive storefronts face strollers of Kossuth Lajos Street in downtown, and the two elegant Habsburg-era hotels along the lake, Hullám and Balaton, are in an embarrassing state of disrepair.

Despite Keszthely's challenges, I’m still drawn to this beautiful and culturally rich city. There’s much to explore even beyond the Festetics legacy: The Balaton Museum, whose engaging exhibit has just the right amount of information about the lake’s folk art, nature, wildlife, and recent history. The mysterious Helikon Park, slightly dim and melancholic because of towering chestnut trees, ringed by handsome villas of Keszthely's upper-middle class during Austria-Hungary. The local farmers' market on Saturday mornings, which hasn't yet morphed into a hipster apocalypse.

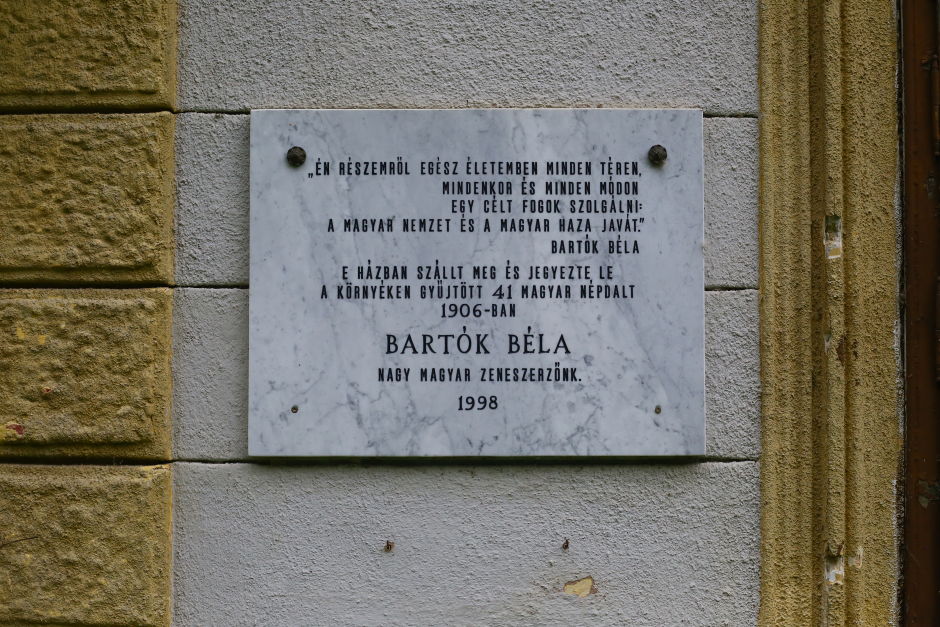

Or the views from the Berzsenyi lookout point in the nearby Keszthely Hills, approached through village houses with thatched roofs. The adorable building of the Szent Mihály chapel, located atop a small hill overlooking the lake. The house, overgrown by ivy, where Béla Bartók stayed in 1906 while collecting folk songs. The list goes on. For better or worse, most places don’t come with conspicuous signs, but a sense of discovery is part of the fun (this map will help you find the places mentioned in this article).

Keszthely's Jewish Past

Keszthely had a thriving Jewish community before the Holocaust, accounting for ten percent of the population. One of its most prominent members was the composer Károly Goldmark. Interestingly, his brother, Joseph, who emigrated to the United States, became a famous physician, and his daughter married Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish member of the Supreme Court of the United States. Keszthely's synagogue still hides in the courtyard of the Goldmark-house, a charming medieval residential building along the main Kossuth Street.

Tragically, nearly all of Keszthely’s Jews were deported and killed in Auschwitz, a total of 829 people. The dilapidated tombstones and crumbling yellow funeral home of the Jewish cemetery today, on the outskirts of town, is a poignant reminder.

A Folk Art Store Worth Visiting

The little shopping I do is at the craft potter in Gyenesdiás, J&A Kerámiaház. Operating out of three old peasant houses, the family sells folklore-themed vases, bowls, mugs and the like since the early 1990s. Best of all is the small exhibition of miskakancsó, 19th-century jars resembling a Hungarian Hussar, complete with conical hat and handlebar moustache. (They also sell them.)

Restaurants, Cafes, and Wineries in Keszthely

While you can find a few new-wave establishments such as Pajti for special coffee and Madárlátta Pékség for sourdough bread and morning pastries, Keszthely is largely devoid of the trendy places that crowd hotspots like Balatonfüred, Tihany, and the Káli-medence. And that's just fine.

Like many people, when I’m at Balaton during the summer, I like to dine at unpretentious food vendors called büfé, which line the beaches – strand in Hungarian – of each resort and serve food from flimsy wooden sheds and people sit elbow-to-elbow with fellow diners. I often go to the less crowded Libás Strand and my go-to orders are lángos, a flatbread topped with sour cream and cheese, and palacsinta, crepes filled with fruit preserves or túró. Occasionally, I order a hekk, a popular fried fish made, ironically, from a saltwater species imported from the Mediterranean (large-scale fishing in Balaton is banned) with pickles and a thick slice of bread.

Near the entrance of Keszthely's main strand is Csaba borozó, my go-to joint for a fröccs, the local wine spritzer in Hungary. It's a modest tavern patronized by locals, many academics, in search of low-priced alcohol (open for most of the year).

For unfussy traditional Hungarian dishes, I head to Park Vendéglő (then pastries at Tulipán across the street from it), or to Öregház Vendégudvar in the nearby village of Vonyarcvashegy where they serve especially tasty fogas (pike-perch), dödölle (a gnocchi-like dish), and Kaiserschmarren out of an updated farmhouse with cane roof (open in the summer only). For a well-made halászlé, the local paprika-laced fish soup, I head to Halászcsárda, a long-standing sitdown restaurant on the south side. For Naples-style pizza: Piccola Napoli.

If I'd like something nicer, I visit Bock Bisztró Balaton, the gleaming white neoclassical estate that used to be the Festetics winery (in Vonyarcvashegy). If it isn't too cold outside, be sure to ask for a table under the columnar porch and take full advantage of the open Balaton vistas.

A fifteen-minute drive will get you to Szent György-hill, one of the most fashionable white wine regions in Hungary currently. On the volcanic hillside perch prominent family wineries such as Szászi, Gilvesy, and 2HA (Szászi has a very pricey and very beautiful panoramic terrace and restaurant). From there, another ten minutes away is the Folly Arborétum (Botanic Garden) in Badacsonytomaj. A magical place with magical views, and its own very good restaurant.

An Iconic Hotel

The monumental Helikon Hotel has been a pride and an icon of Keszthely since its opening in 1971. In days of yore, the hotel drew Communist party elites and Western tourists with its private beach-island, panoramic lake-views, and TV-equipped rooms. Today, after a recent gut renovation, the four-star superior hotel is once again Keszthely's most upscale accommodation with astonishing vistas.